Linguistic Entanglements in the Animal Kingdom

During the week of October 21 to 27, 2013 the Academy of the Jewish Museum Berlin, in cooperation with Kulturkind e.V., will host readings, workshops, and an open day for the public with the theme “Multifaceted: a book week on diversity in children’s and young adult literature.” Employees of various departments have been vigorously reading, discussing, and preparing a selection of books for the occasion. Some of these books will be introduced here over the course of the next few months.

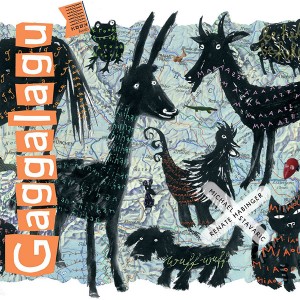

With strange combinations of letters on the feathers, fur, and skin of different animals who stand lost upon a map: I was so drawn to the cover picture of Gaggalagu that I instantly reached for it in our reading group.

With strange combinations of letters on the feathers, fur, and skin of different animals who stand lost upon a map: I was so drawn to the cover picture of Gaggalagu that I instantly reached for it in our reading group.

Released in 2006 by kookbooks, through a publisher that until now I only associated with volumes of poetry for adults, it is very appealingly and elaborately designed. It was a surprise to learn that this little press also publishes children’s books. Before this, I had also never heard of the author, Michael Stavarič, and the illustrator, Renate Habinger, was new to me as well.

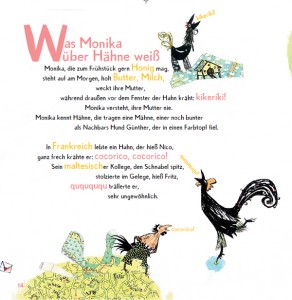

The first two pages are made of transparent green paper. Written on the first page is a series of fantastical sound combinations: Gaggalagu, koekelekoe, ake-e-ake-ake. Only when you press these sheer pages against the next ones does it make sense: a rooster stands in the center and the odd sounds are assigned to various countries. The subject is the call that a rooster makes – and how people translate it into all their respective languages. And thus begins a story about the language of the animals.

While I can render the kikeriki of the German rooster melodically enough and species-appropriate to my ear, I can’t manage at all with the rooster’s call from South Africa: koekelekoe. My voice sounds too monotonous. I try to articulate one letter after another as if I were just learning how to read.

“No rooster sounds like that,” says my daughter, trying to transfer the singsong of kikeriki to koekelekoe herself. That already sounds much better. And as we practice all the different rooster calls with the same kikeriki melody, I wonder who could teach me about the ‘right’ melodies. How is the Vietnamese rooster’s o oo o supposed to sound?

When I’ve finally finished the first page, the time I usually allot to an entire book is up. But naturally I have to read until the end because there aren’t just roosters, there are dogs, ducks, even fish. And the book doesn’t just require time and intense concentration for the Babylonian imbroglio of the language, but also for the little stories and poems all around it. Sometimes I flounder and stumble over the sentences, and then I ask my two children: “Did you understand?” “No.” I start again from the beginning and at last my daughter grasps the story and explains it to me: “Monika understands the rooster language – but her mother doesn’t.” Sure, I think to myself, that’s what the text says.

Pondering the question of speech melody again, I wonder whether Michael Stavarič – who lives in Austria, after all – would give the text another melody altogether, by which the meaning would reveal itself to me. But my children so greatly enjoy these sentences and words that I suppose, at last, perhaps the emphasis and inflection are not so important after all. I read further,

“Bring the harvest to the miller, Mr. Yarmer, a distiller – and a farmer – come and help! Sheep like to call conventions, are immune to wet conditions, they direct traffic all with ease, no batons or pistols, please. In Arabia: baa baa! In Croatia: bee hee! In China: mieh mieh! In Iceland, just: me me! What a muddle! And in Vietnam? There lives a man, he has a sheep who keeps him warm. His sheep bleats: beh ehe ehe. You know what else? He calls his wife, Ahem ahem.”

An odd kind of humor, I think, but it works.

It is getting late when we finally put the book down. Shortly before falling asleep, my three-year-old son asks me: “Which rooster says cocorico?” “The rooster from France,” I reply. “The one from Paris?” “Hm.” “And what do dogs say in Italy?” “I don’t know. Va, va, va?” “No. Bow, bow, bow. They just can’t stop being amazed.”

Who, exactly?

For their sensational book Gaggalagu, Michael Stavarič and Renate Habinger were 2007 recipients of the Austrian Children’s and Young Adults’ Literature Prize. Michael Stavarič will be at the Jewish Museum for a reading on October 25 and 27, 2013 – and I am already eager to find out what melodies he will give to the many animal sounds.

Nina Wilkens, Education

Michael Stavarič, Renate Habinger, Gaggalagu, Berlin: kookbooks 2006, 48 pages. [English translation of the quotations for this blog post by Margaret Bell]