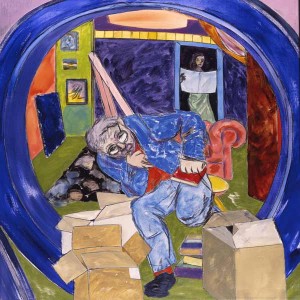

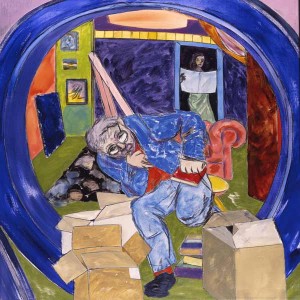

Kitaj once said that books are for him what trees are for a landscape painter. His ateliers in the London neighborhood of Chelsea and in Westwood, Los Angeles, were crammed full of books, on shelves, around his easels and piled up on the floor.

R.B. Kitaj, Unpacking my Library, 1990-1991 © R. B. Kitaj Estate

He was already ranging through the cheap bookshops on 4th Avenue – the largest bookselling district in the world – on his way to Cooper Union when he was a student there. He found the modern classics like James Joyce, Ezra Pound, T.S. Eliot, and Kafka, as well as journals such as the “Partisan Review” and the American surrealist magazine “View.” In Oxford, his teacher Edgar Wind introduced him to the Warburg School and he bought a complete set of the famous “Journals of the Warburg Institute.” His visual imagination was fuelled by the illustrations for the “Afterlife of Antiquity,” copperplate engravings made according to ancient templates. In 1969, Kitaj published as silkscreens 50 book jackets from his personal library, in an edition that he called “In Our Time: Covers for a Small Library after the Life for the Most Part.” → continue reading

I am impressed above all with R.B. Kitaj’s collage-like works, produced by superimposing numerous pieces of information and artistic citations. With their powerful colors, they radiate at first a kind of lightness and beauty.

R.B. Kitaj, Desk Murder 1970–1984 © Birmingham, Birmingham Museum and Art Gallery

The actual stories behind the motifs become clear only when one reads the texts that Kitaj attached to his pictures. These additional levels turn the collages into fraught projection screens for personal, historical, political, cultural, and religious themes and events. Suddenly text and image can no longer be viewed and understood separately. A putatively beautiful, gaily colored work becomes a vexating puzzle. → continue reading

Searching for a Jewish past is the topic of Jonathan Safran Foer’s Tree of Codes. His best-selling, Hollywood-adapted debut novel Everything is Illuminated (2002) already depicted a young man on a trip to the Ukraine in search of his family’s past.  His new book is also a search for Jewish roots, though this time artistic, rather than biographical.

His new book is also a search for Jewish roots, though this time artistic, rather than biographical.

Experimenting with the concept of absence, the book reproduces parts of Bruno Schulz’s Street of Crocodiles, the English translation of one of two surviving texts of a writer, whose other works were lost when the National Socialists seized his Polish hometown Drohobycz in 1941 and murdered its citizens, including Schulz, in 1942. As if to depict the loss of literature by destroying the letters in a book, Foer cut into Schulz’s pages, leaving only select words and half sentences behind, thereby reducing, already in its title, Street of Crocodiles to Tree of Codes. → continue reading