Eric Silverman’s long-awaited Cultural History of Jewish Dress was released last month in Bloomsbury’s prestigious fashion history series (formerly Berg). It brings up to date a subject which has long been in want of revision: Jewish clothing was last surveyed in 1967 – almost fifty years ago – by Alfred Rubens in A History of Jewish Costume. The scope of the book is broad, spanning three thousand years in regions and cultures as distant from one another as the Middle East, Russia, North Africa, Europe, and the USA.

Eric Silverman’s long-awaited Cultural History of Jewish Dress was released last month in Bloomsbury’s prestigious fashion history series (formerly Berg). It brings up to date a subject which has long been in want of revision: Jewish clothing was last surveyed in 1967 – almost fifty years ago – by Alfred Rubens in A History of Jewish Costume. The scope of the book is broad, spanning three thousand years in regions and cultures as distant from one another as the Middle East, Russia, North Africa, Europe, and the USA.

Drawing on the Torah, Mishnah, and Talmud, on a selection of secondary sources and newspaper articles in English, Silverman, a US-American anthropologist, chose an analytical rather than empirical approach. Instead of categorizing garments, he chronicles controversies fought over the ages about what Jews should and should not wear.

The result is a treasure-trove of anecdotes reflecting changing conceptions of clothing from Biblical times to today. Silverman cites Ben-Meir and Oz on the invention of the sandal, “the most widespread item plucked from the biblical wardrobe,” as in fact “an invented tradition, dating to the generation of Russian Jewish émigrés who arrived in Palestine in the early twentieth century.” He explains how the Star of David emerged in the nineteenth century in a concentrated search to find a secular symbol for Jews. Silverman draws transcultural analogies for rituals involving clothing, such as the chalitzah shoe ceremony, which he intriguingly posits as an inversion of the Cinderella fairy tale, or the significance of knots as an early form of contractual binding for Jews as well as for Papua New Guineans.

These examples aside, Silverman’s perspective on Jewish costume history is distinctly American. Scholarship in languages other than English is not represented, which is a disadvantage in the treatment of European clothing debates. As a result, these are presented in insufficient detail and with historical mistakes. In terms of style, Silverman’s “coolness” occasionally misses its mark: “Fringe Benefits,” as a chapter-heading for tzitzit (fringes) is one of several unfortunate puns (the worst being a double entendre about Jews forced to wear the yellow star in 1941: “This time, truly, Jews were dressed to kill.”)

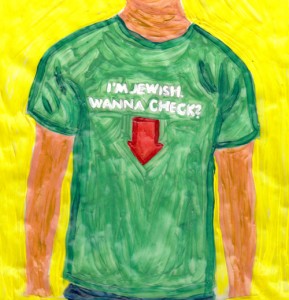

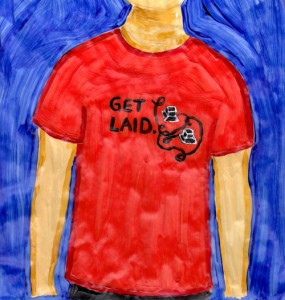

Three case studies on current clothing trends in the USA, on the other hand, are a great contribution to Jewish studies and costume history. Silverman explores the wardrobe of Orthodox and ultra-Orthodox Jews, uncovering a minutely hierarchical signalling system expressed by means of hats, breeches, and outerwear material. He succinctly chronicles the proliferation and design of the kippah (scullcap) over the last half-century. And he most compellingly deciphers the messages behind Jewish slogans on hipster T-shirts, arguing that their wearers seek to replace the stereotype of Jewish bookish docility with utterances of confidence and sexiness: “GET LAID.” printed on one T-shirt, for example, shows a picture of tefillin, (phylacteries, which only Jews would know are “laid” on arm and head); “I’m Jewish Wanna Check” has an arrow pointing tellingly downwards. Judging from Silverman’s analysis, Orthodox and hipster clothes seem relate to one another – again, inversely. As secular Jewish casual wear attracts attention with increasingly vulgar slogans, modesty becomes a value scrutinized in Orthodox circles more and more ferociously.

Three case studies on current clothing trends in the USA, on the other hand, are a great contribution to Jewish studies and costume history. Silverman explores the wardrobe of Orthodox and ultra-Orthodox Jews, uncovering a minutely hierarchical signalling system expressed by means of hats, breeches, and outerwear material. He succinctly chronicles the proliferation and design of the kippah (scullcap) over the last half-century. And he most compellingly deciphers the messages behind Jewish slogans on hipster T-shirts, arguing that their wearers seek to replace the stereotype of Jewish bookish docility with utterances of confidence and sexiness: “GET LAID.” printed on one T-shirt, for example, shows a picture of tefillin, (phylacteries, which only Jews would know are “laid” on arm and head); “I’m Jewish Wanna Check” has an arrow pointing tellingly downwards. Judging from Silverman’s analysis, Orthodox and hipster clothes seem relate to one another – again, inversely. As secular Jewish casual wear attracts attention with increasingly vulgar slogans, modesty becomes a value scrutinized in Orthodox circles more and more ferociously.

A Cultural History of Jewish Dress reads clothing controversies as discussions about the status of Jewish religion and culture – convincingly. Applying Silverman’s theory to today’s trends, the compatibility between Orthodox and hipster Jews is in an unprecedented decline.

(Eric Silverman, A Cultural History of Jewish Dress, London/New York: Bloomsbury Academic 2013.)

Naomi Lubrich, Media