Why a particular subject captures the interest of the public at a given time is not always immediately apparent. Conversion, for instance, has become the topic of conferences, lectures and exhibits in German-speaking Europe without any notable change in its social significance nor religious practice.

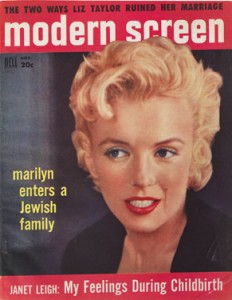

Picture in the current special exhibition “The Whole Truth” accompanying the question: Jew or non-Jew? Marilyn Monroe on the cover of the Modern Screen Magazine, November 1956

© Jewish Museum Berlin, photo: Jens Ziehe

The number of converts to Judaism is invariably small. According to the data collected by the Zentralwohlfahrtsstelle der Juden in Deutschland, on average 64 conversions are carried out yearly in the various German-Jewish communities, and since the year 2000, the number has remained fairly stable. Nor has the size of the Jewish communities varied much. For over a decade, the number of members has stabilized at around 105.000. In relation to the size of the community, the total number of converts since 1990, 1.366, makes up under one percent of the Jewish community. The number of Jews leaving the communities is slightly higher, around one hundred a year, yet the number is not particularly meaningful, because it includes people who leave for all sorts of reasons, including financial. By all accounts, today’s Jewish converts are a minute and exotic minority.

Yet the topic is currently being discussed with much enthusiasm. The ETH Zürich held a series of lectures on conversion in fall 2012 (“Konversion. Interreligiöse Übertragungen, Grenzziehungen und Zwischenräume”), just after the University of Trier held a conference on the same topic in June 2012 (“Orts-Wechsel, Blick-Wechsel, Rollen-Wechsel: Konversion in Räumen jüdischer Geschichte”). The Jewish Museum Berlin’s special exhibition “The Whole Truth” presents the fluidity of Jewish identity with biographies of Jews, non-Jews, part-Jews and several converts, among them the actress Marilyn Monroe. Most significantly, the Jewish museums in Hohenems, Frankfurt and Munich together with many cooperating partners, are showing a joint exhibition on conversion, called “Treten Sie ein! Treten Sie aus!” Their perspective is cultural, ritual and psychological, with exhibits and texts illustrating individual conversion stories in three phases of the process: the before, the passage itself and the aftermath. The stories are anticipated by pictograms displaying the religions rejected and adopted. These cover a wide range, including Christianity and Islam, but also Schamanism, Buddhism – and, humourously, Pastafarianism, an atheist parody of religion, which pays tribute to a spaghetti monster as an object of worship. The texts are concise, sometimes ironic, and inclusive, with contributions by converts as well as scientists and intellectuals in the catalog and the extensive program of events.

If not practice, what then accounts for the widespread interest in a ritual only few are engaging in? Looking around, what characterizes modern German spirituality is not a mass movement to substitute one religious culture for another, but either the attempt to reconcile multiple – on a personal level, in relationships, and within communities or societies – or the rejection of religion. According to the European Commission’s Eurobarometer (2005), the majority of Germans are not religious. Christian churches, which have been facing dwindling numbers of adherents for many years, have begun discussing whether and how to rededicate their buildings. And even the Jewish communities are not nearly as large as they could be. While more than 200.000 Jews have immigrated to Germany from the former Soviet Union alone, the communities number only half that size, which means that the large majority has chosen not to join them. If conversion is becoming a popular subject of debate, perhaps this is due to it being a foil for discussing precisely what it is not: namely, religious loyalty.

Naomi Lubrich, Media