Teddy bear that belonged to Ilse Jacobson (1920-2007), textile, straw, glass, ca. 1920 to 1930, in our online collection

56,250. This is the number that comes up when I search our collection’s database for its complete holdings. 56,250 data sets describing, for the most part, individual objects, and occasionally entire mixed lots. You can now see 6,300 of these objects online. Releasing this information to the public provokes mixed feelings on the part of museum staff: we have a lot to say about many of these objects. Many of them don’t speak for themselves. You can’t tell, for instance, that this teddy bear belonged to a child emigrating from Germany. The meaning of many documents and photographs lies likewise to a large extent in their biographical or political history. They require sufficient detail and well-chosen catchwords to help visitors find other objects related to the same topic.

With this project, we have to proceed pragmatically. 15-30 minutes of working time per object is a lot if you have to inventory a mixed lot with 250 units. We verify everything, including things that occur to us as we’re working. We are aware that there’s more to write about – and there would be more to correct, – if we had the time for more thorough research. Yet we can only make forays into the library or even into the archive for special projects or particularly important objects. And so we rely to a great extent on digital sources.

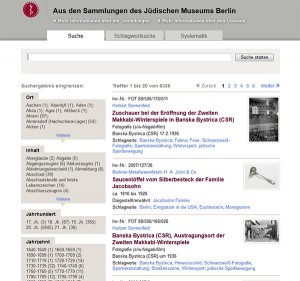

Screenshot of the online-search in the Jewish Museum Berlin’s collections

Today, researchers are accustomed to having easy access to information. Ten years ago, I had to put one microfiche after another into the state library’s reader to search through old Berlin addresses. I had good intentions, but not enough time to get the results I was searching for. Now you can glance at the Berlin library website and find your answer: how long has this company existed? Is its main office in Berlin? Has it ever changed its name, and if yes, when? Learning that the cigarette makers “Mahala” were called “Problem” in 1912, for instance, helps us date cigarette advertisements correctly.

Magazines are important sources of information. Our largest inventory of photographs, the collection of Herbert Sonnenfeld, includes many shots published in the 1930s in Jewish newspapers and magazines. A quick look – when was the photo published? Do we have the right title? Is there additional information? – and the scholar’s mind is at ease about publishing the data on the web.

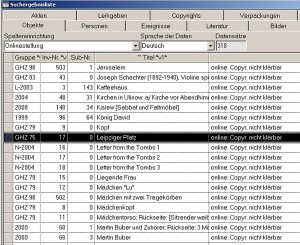

List of search results from our internal collections data bank, objects with unresolved online copyright

It is frustrating when sources that were once available online disappear. Like many in our field, we were hard-hit when the digital access to the periodicals of “Exilpresse digital” and “Jüdische Periodika in NS-Deutschland” were deactivated. Varying national regulations are also exasperating. We, in Germany, are not allowed to show many of our holdings from the 20th century due to copyright protection laws. Yet one mouse-click away, the Leo Baeck Institute can make public the exact same, or similar, objects, because the “fair use” regulations in the USA allow a much more advanced provision of materials.

Our users aren’t usually aware of these differences. We don’t expect them to grasp, among other constraints, why the LBI can show a portrait of the artist Josef Oppenheimer, but we have to wait until 2037, 70 years after the artist’s death, to show his pastel of Leipziger Platz in Berlin.

There are wonderful, useful things on the internet. We use it ourselves and try to expand it as well. A great deal must still be done to make it easier to access the holdings of knowledge that cultural institutions possess, as the German Association of Museums recently urged in its position paper. Because facilitating this access is one of the core jobs of a museum.

Iris Blochel-Dittrich, Documentation of the collections

PS: This Thursday and Friday the conference “Zugang gestalten” (Creating access) will deal with the various implications of digitalization and the question of why access to cultural heritage should be a public project.