One of the works in our art vending machine is a booklet which provides an insight into the inner-workings of many of the Israeli Kibbuzim. With sober drawings and a text that is based on archival documents, artist Atalya Laufer (b. 1979) exposes a particular aspect of growing up on a Kibbutz. As one of the last generation of children to be raised in communal children’s houses (Batei Yeladim), she takes us on a journey through time and into the passing world of the Kibutzim.

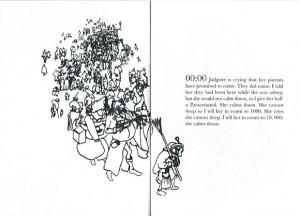

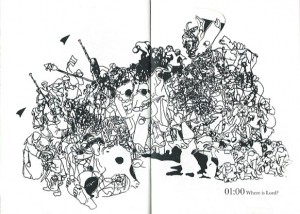

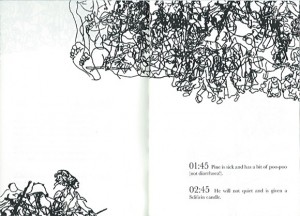

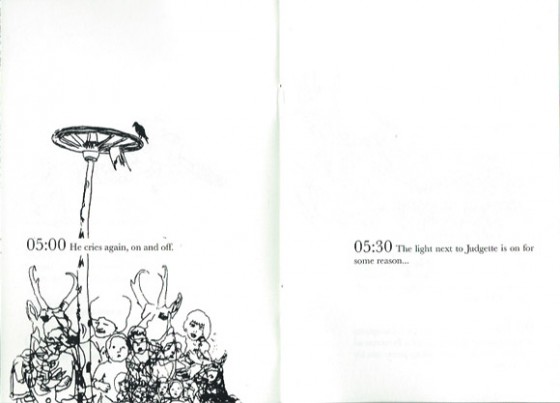

The text in the booklet is based on protocols of night shifts that were taken in the early 1970s. In these protocols incidents and particularities in every house, during every night shift, had been recorded. Owing to these we can readily reconstruct the daily life in children’s houses.

“I simply do not know what it is like to live with my parents. I find it fascinating that as a child, if I were woken up by a bad dream, I would have had to get out of bed and into the hallway where I could cry onto a small reciever hung up high on the wall with the hope that someone (the person on a night shift) would come. Today, this seems really odd to me.“

The names in the booklet have been translasted quite freely. As often the case with Israeli names, they are names of animals, trees or have biblical origin. The translation allows a distance from the original material, and at the same time, creates an enigmatic narrative, somewhere between a straightforward childrens tale and a surrealistic, dark but humorous one.

In turn, the drawings play with the text and the names associatively. They are based on photographs from the kibbutz as well as on paintings by Pieter Bruegel. The connection between Flemish history, genre painting and life on the Kibbutz is also somewhat puzzling. Atalya explains:

“To me, there is a clear link between Brueghel and the Kibbutz. If my memory doesnt fail me, there were often framed reproductions on the walls of the children houses or, my parents may have had a book of his prints. But, of course, perhaps needless to say, Breughel is regarded today for his detailed representation of ‘mysterious’ peasant life. The comparison between Kibbutz and rural life is relevant, at least on the level of ‘mysterious’ innate structures, traditions, languages and rituals that for an ‘outsider’ may be difficult to understand but at the same time likely to find fascinating.”

For Laufer the process of artistic appropriation of a particular reference material begins often with drawing from a reproduction of the original. After this relatively direct transformation, she develops the image into a complex of lines and motifs through layering several drawings on top of each other until. Similarly, the text is also a collage of several text extracts.

Laufer refers to her works as “appropriated readymades”. The book is neither biographical nor fictitious and can be neither easily pigeonholed or taken out of a particular drawer. Nevertheless, with a bit of luck on your next visit to the museum, you could pull out one of the booklets from the art vending machine. Flipping through a few pages of the booklet offers an impression of Atalya Laufer’s artwork.

You can learn more about Atalya Laufer on her website:

http://www.atalyalaufer.turnpiece.net/image/34715

Christiane Bauer, Exhibitions