My Week of Intensive Research into Fred Stein’s Archives

In June of 2012 I had the opportunity to delve into the estate of Fred Stein. During the preparation for our then-upcoming exhibition “In an Instant,” I travelled to the little town of Stanfordville, NY to visit Peter Stein, the photographer’s son and archive administrator. For a week, I studied the voluminous and multi-faceted material stored in various rooms of the private residence. It was an unforgettable immersion into the life and work of Fred Stein.

Hundreds of negatives, kept in fireproof cabinets, make up the core of the collection. Their differing formats point to the two cameras Stein photographed with: coiled strips of Leica negatives and individually packaged 2 1/4 x 2 1/4 inches negatives in pergamin sheets from the Rolleiflex. The cameras themselves unfortunately didn’t survive. Among these negatives, you can see Stein’s first shots of Dresden shortly before he emigrated to Paris in 1933.

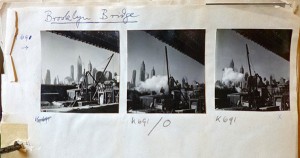

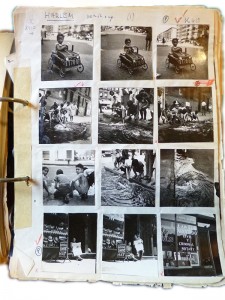

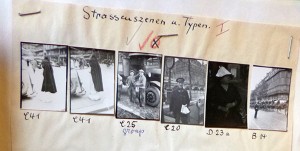

Binders full of contact sheets offer a good overview of Fred Stein’s œuvre. His pictures of Paris in the 1930s are set apart from those of New York in the 1940s and from the portraits he took throughout his life. Most of the captions in these binders were written by his wife Lilo and appear in German, French, and English, the languages of the three stages of the Steins’ life.

In addition, many original prints still exist, predominantly 8 x 10 inches in size, both on matte and glossy paper. Regrettably Fred Stein never signed his prints. You find his signature only on a few original mats. He also never assigned titles to his photographs. Most of the pictures can be distinguished, however, by the captions on the negatives and sometimes also a date and short working title on the back side of the prints.

Beyond the photographs themselves there is an extensive correspondence consisting of personal and business-related letters. There are many pieces of writing that reveal a photographer’s everyday problems: a number of reminders requesting payment for even the smallest fees offer insight into Stein’s financial situation. Innumerable demands to respect copyright suggest how frequently his photographs were published without an indication of authorship.

One letter that Fred Stein wrote in 1946 to friends and relatives elaborates on what befell him and his wife during their emigration and also describes the difficulties they had during the war. For instance, we hear about how Stein was interned as an “enemy foreigner” in various camps in France starting in 1939, about his successful escape by foot to the south of France and reunion there in 1941 with his wife and daughter. Personal documents like this letter as well as family photographs afford a moving look at the private life of Fred Stein, who only became a photographer once he was in exile.

For me, surveying his archive was an intense experience with lasting effects. I would like sincerely to thank Peter Stein and his wife Dawn Freer for inviting me into their home. Pieces of the puzzle that my previous research exposed came to fit together over my week in New York and motifs I’d already noticed were complemented by ‘new discoveries.’ This trip reinforced initial ideas for the exhibition: the concept as it was implemented, the way biography and work closely intermeshed. You still have a chance to see the show until 4 May in the Eric F. Ross gallery of the Jewish Museum Berlin.

Theresia Ziehe, Photography collection and curator for the exhibition “In an Instance”