The financial crisis of 2007 had an impact both on the countries of Western and Eastern Europe. The złoty may still glitter but it has long since ceased to be the “golden coin” Polish currency was originally named for. Unemployment and stagnant economic growth, rising real estate prices and declining purchasing power have put the brake on Poland’s economic recovery. The Netherlands has likewise been in recession for years. Declining competitiveness, private debts, state-subsidized home ownership, the low retirement age and the expensive health care system have fed uncertainty and repeatedly paved the path to success for the Freedom Party of the populist xenophobe Geert Wilders.

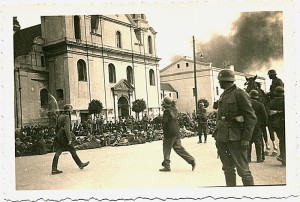

This downward spiral in state treasury and personal funds led a couple of Polish resp. Dutch wheeler-dealers to scrape the barrel for a bilateral business model. Crafty Dariusz Woźniok and his fly-by-night Dutch client somehow managed to get their hands on infantrymen’s photos from the Second World War—whether as thieves or buyers it is impossible to say. Maybe they were embittered by the fact that no share in the tidy profits made from material goods ever came their way, from the export of Polish geese, strawberries, potatoes and beetroot, for example, or of Dutch cheese and tulips. Maybe they hatched their business plan in an Amsterdam coffee shop and had simply smoked one hash pipe too many. Whatever the case, they figured: “It was a sure bet that snapshots of ghettos and so-called ‘Jewish actions’ in early 1940s Poland could be sold off as ‘Holocaust-ware’ to Jewish Museums—so why not make the most of an historic windfall?”

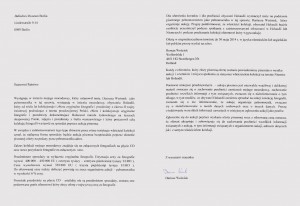

Like Lolek and Bolek they set to work: on behalf of his client, an unnamed “Dutch citizen,” Dariusz Woźniok dispatched an offer to addresses all over the world, some of which he copied incorrectly from the Internet: to various Jewish museums and presumably also to private collectors. The letter was written in Polish and had neither a letterhead nor date—“but it’s bound to arrive,” Dariusz must have thought; “and anyone who takes an interest in the Holocaust also understands Polish.”

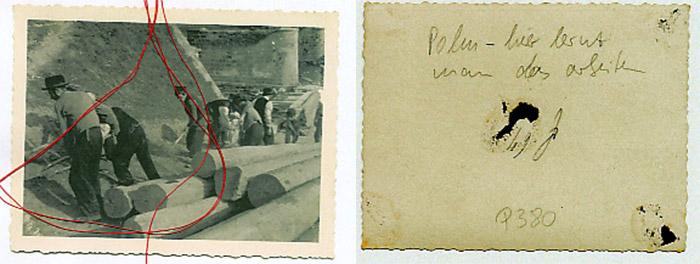

Said windfall comprises around 150 photographs and a handful of objects, such as plain Kiddush cups, charred tefillin, dirty kippas, threadbare bags, and stained prayer shawls, mostly fairly old although neither date of origin nor provenance were stated. A CD containing photographs of the front and rear view of each object was enclosed as proof. A red thread had been laid across each of the photographs so as to up the chances of claiming copyright fees, should the photos ever be reproduced. On the assumption that the institutions approached would all be avid to acquire such material it was proposed that the “delicate matter” be dealt with by written auction—and in total exclusivity, without the involvement of any certified auctioneers. Interested parties were to submit written offers to 4651 HG Steenbergen, the address given in the letter. At 3 000.00 euros per photo, the two gentlemen were reckoning with total booty of up to 450 000.00 euros. It goes without saying that the size of the transaction prompted both Dariusz Woźniok (or whoever may have been hiding behind that name), and his anonymous client to insist on absolute confidentiality. Their paranoia does not mean that no one is out to get them.

Cilly Kugelmann, Program Director