Victor Alaluf in his studio in Berlin-Friedrichshain © Jewish Museum Berlin, photo: Denis Grünemeier

A retro-style armoire with a skull sitting on top of it—a piece from the collection of Victor Alaluf, an artist with Argentinian roots whom I interviewed recently in his studio in Berlin-Friedrichshain.

In his work—installations, mainly, comprised of drawings, collage, sculpture, video art and everyday objects—Alaluf addresses the existential issues raised by our experience of death, pain, and the ephemeral and fragile nature of all living creatures. His choice both of material and objects is decisive. He frequently chooses brittle materials, such as glass or ceramics, as well as organic matter, such as human hair and blood. Alaluf has a particular penchant for damaged or “useless” materials. Thus the wood used to frame some of his more recent artworks is timber flooring salvaged from a local building under refurbishment. Alaluf takes such finds home for use in his art and so saves them from disappearance. He also trawls flea markets for objects he can integrate in his work because he is fascinated by the patina of old wooden clocks, furniture and the like: the artist is drawn to the traces of time and to the human stories behind them. He regards this as “essence.”

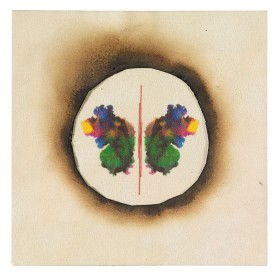

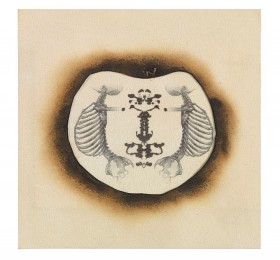

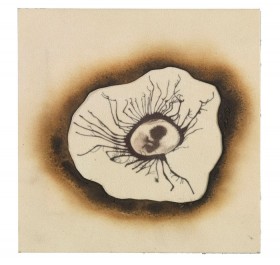

Victor Alaluf, „Essence“, Ink screen-printing on hand-burned velvet, 2013, Berlin 2014 © Jewish Museum Berlin, photo: Jens Ziehe

It seems to me that Alaluf’s art somehow reflects his own biography—the leukemia he once suffered but managed to overcome. As he explained to me, the medical needles he once used to affix silhouettes to a backdrop point to that experience. Alaluf pays reference to physical sickness and processes of healing likewise in “Barefoot in the Dark,” a video piece from 2014, which portrays a man tortured by pain who is undergoing treatment. Pulsating MRT scans of the human brain are intercut with other footage. Iconographic motifs such as the thorn of crowns come into play when it seems as if all possible evil will be visited on this man. Ultimately, however, the image of a brilliant blue sky conjures rebirth and life and a flutter of butterflies—a symbol of hope for the artist—decoratively weaves its way across the screen.

Victor Alaluf created numerous editions of his work series “Essence” for the art vending machine in our permanent exhibition. They were first available for purchase in early summer this year and have unfortunately already sold out.

Victor Alaluf, „Essence“, Ink screen-printing on hand-burned velvet, 2013, Berlin 2014 © Jewish Museum Berlin, photo: Jens Ziehe

Each work consisted of two pieces of velvety paper stuck together, one atop the other. A round area at the center of the upper layer had been sufficiently charred to reveal the lower layer to which three different motifs had been applied using the silkscreen method. One motif in luminous color was reminiscent of human lungs or possibly of butterfly wings; another showed a finely sketched, stylized human skeleton; the third a human embryo in its amniotic sac. The combination of soft velvety paper, coats of translucent color and fine spidery lines conjured the impression of something fragile yet vital. At the same time, the charred area made it easy to imagine how quickly flames might engulf these things and destroy them.

In “Essence,” Alaluf juxtaposes apparent opposites—life and death, birth and extinction. He simultaneously suggests through his art that these realms are not opposites but irrevocably intertwined. Wherever a flame had been put to work, new images had emerged and new layers had been exposed. And yet the two pieces of paper remained in communication with one another, and interwoven: the dark brown lines extending from the embryo ended at the edges of the charred paper and merged there with its similar hue.

Victor Alaluf, „Essence“, Ink screen-printing on hand-burned velvet, 2013, Berlin 2014 © Jewish Museum Berlin, photo: Jens Ziehe

“The viewer should be able to see into the past as well as into the future, should be able to deal with things flooded with light as well as with darkness,” wrote Alaluf in a commentary on his work. “It is impossible for a young Jew living in Berlin today to evade such complex perceptions. Berlin is a city that inspires hope and the subject of this artwork is precisely that. It gives expression to a firm inner conviction that something new and vital can arise from the ashes of destruction.

Denis Grünemeier, curator of the exhibition “Bedřich Fritta: Drawings from the Theresienstadt Ghetto”