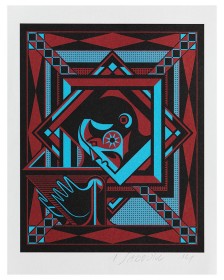

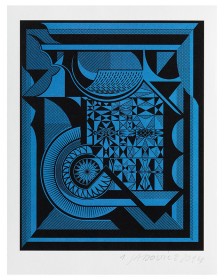

I’m meeting Georg Sadowicz in his atelier in Berlin-Hohenschönhausen. The Berlin-based artist was born in Liegnitz, Poland, on the German border. Since April, two of his pieces – precursors to larger work – have been made available to visitors as a limited run in the Jewish Museum Berlin’s art vending machine. They are titled, “The Cantor” and “The Mill.” Sadowicz’s atelier is a mere hundred meters from the grounds of a former Stasi detention center, now a memorial site. The sight of it troubles me, but the unease vanishes as soon as I step into Sadowicz’s atelier.

Georg Sadowicz has an eventful life story. When he was 16, his family moved from Poland to Nuremberg in West Germany. He went onto study visual arts in Dresden and was a protégé to Ralf Kerbach, who taught at the College of Visual Arts, Painting and Graphic Design there. Max Uhlig was also a major influence on Sadowicz, serving as his mentor and supporter. Moving to Berlin permanently about 15 years ago, he found the artistic and financial possibilities he couldn’t in other cities.

Immediately following his studies, Sadowicz focused first on painting then on linoleum cuts. Each image in the creation of a linoleum cut goes through a complex production process from the first template to the negative cutter in the material to its final coloring. The result isn’t always predictable: “Some templates have been lying around my atelier for more than a year while others seem to fail through the course of printing. You could compare the emergence of my work to a game of chess. I plan the moves in advance and want to win. But they could be wrong. You don’t know until the end of the game,” Sadowicz says about the difficulties inherent to the process, adding that he learns a great deal from failure.

Linoleum cuts inform his general approach to art. With the exception of the works made available for the art vending machine – offset prints based on smaller linoleum cuts – the artist mostly deals in large-format cuts. For Sadowicz, it’s important that the “common perspective of spatial constructs of classical art doesn’t apply when viewing it.” He is constantly questioning the traditional separation of foreground, middle ground and background. This is evident in most of his work, in that it does not contain an escape point. “I organize all the elements in a rhythmic repeating interplay so space remains ambivalent. A great deal is happening at the same time on all three levels: fore, back and middle.” This gives the appearance that many forms are part of a larger whole, which in turn seems to be further subdivided into more detailed scenes and symbols. Such is also the case with Sadowicz’s small-format works in the art vending machine.

My interesting visit to Sadowicz’s atelier lingers in my thoughts, not least of all because he’s given me insight into the precarious situation for many Berlin-based artists. Sadowicz told me of his former atelier in Kreuzberg, which over time became too expensive. His move to the factory building in Hohenschönhausen is emblematic of the relocation of Berlin’s artists from the center to its outskirts.

Kilian Gärtner – who now no longer finds it necessary to search for escape points in art – made his way to Hohenschönhausen.

P.S.: Further information about the artwork and the other artists of the art vending machine can be found here.