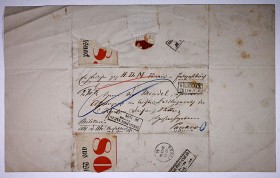

Letter accompanying the award certificate for the Order of the Red Eagle, Fourth Class, bestowed upon Emmanuel Mendel © Jewish Museum Berlin, gift of Wolfang Schönpflug, photo: Ulrike Neuwirth

A huge number of objects enter the collection of the Jewish Museum Berlin every year. Each must be inventoried and studied. Many of these items have a long history, often having circled the globe. Having survived flights, emigration and decades of storage, some documents are in such bad shape, they cannot be used without further damaging them. As paper conservators, our task is to at least conserve, if not restore, these objects, so that they can again be handled without exposing them to additional wear and tear.

In the conservation process, it’s absolutely vital to understand and respect an object’s historical, technical and aesthetic dimensions. Before beginning any treatment, the object must be comprehensively analyzed and sometimes intensively researched to know whether damage is the result of actual misuse or part of its story. The goal is not to return the item to a “like new” condition but, on the contrary, allow existing damage to remain if it’s discovered to be an essential facet of the item’s history. Only then are the appropriate conservation measures taken.

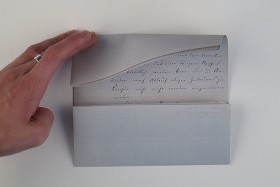

Reconstruction based on to-scale photo prints: the double-layer page with the message was folded in such a way as to conceal the content within…

The Mendel Collection has been particularly fascinating to look into. The Berlin neurologist and psychiatrist, Prof. Dr. Emanuel Mendel (1839-1907), specialized in epilepsy in Berlin and Breslau and, immediately following graduation, opened a medical practice in Berlin’s Pankow district. Later, he taught at a well-known clinic for neuropathology. In 1884, he was appointed Associate Professor at Berlin’s Friedrich Wilhelm University. Mendel also had a political career, serving between 1877 and 1881 as a representative in the Reichstag for the Fortschrittspartei. In 1893, he became a founding member of the Central Association of German Citizens of Jewish Faith. Prof. Dr. Wolfgang Schönpflug, Mendel’s great-grandson, donated the Mendel Collection to the Museum in 2013.

Four documents required particular attention, among them a letter acknowledging Mendel’s receipt of Prussia’s Order of the Red Eagle, as well as other official letters. They date from 1864 to 1867 and consist of double-layer paper – the left half addressed to the recipient and the right hand for the text of the letter. Remnants of stamps and seals are also visible. All four letters shared common types of damage. Three contained major blemishes on the lefthand sheet as well as tears and paper fragments in the area of what remains of the seal.

…The fold created a flap for one page to be pushed into. Then the folded letter was sealed and addressed. The seal must be broken to open the letter…

The papers’ characteristics suggest they served a double purpose as envelopes. Whereas today letters commonly go into a separate envelope, those at the end of the 19th century had a variety of uses. Then, letters were folded so as to be unreadable from the outside. Seals made of wax, resins or thin paper covered in dough were applied using a number of technical processes for closing a letter and ensuring its authenticity. Quite often, the seal’s material would include a signet of a crest or monogram printed onto the letter and pressed into the seal. The address would then be written on the fold along the front side, appearing to us today as rotated 90 degrees. Delivery would be carried out by couriers or the official postal authority, hence the presence of the stamps. The recipient could then open the letter merely by breaking the seal.

… Only then could the letter be unfolded and read. The folds are clearly visible and are even more so in the original letter. © Jewish Museum Berlin, photo: Stephan Lohrengel

Scaled photo prints helped us to reconstruct the letters’ folds and seals. The reconstruction made it possible to reduce the visible damage along the opening of the sealed letters. What was initially seen as damage was therefore actually an integral part of the letters themselves. That’s why we opted to preserve them in the condition in which they came to us. We left the adhesive on the seal fragments as it was, rather than filling in corresponding spots. We further refrained from reconstructing these spots, only stabilizing the tears and more delicate areas with thin japanese paper, thus allowing the original folds and damage along the opening to remain visible. Now these four preserved letters can be safely stored in our archive for academic purposes, to be used in archive workshops or perhaps be shown someday in our permanent exhibition.

Paper conservators, Stephan Lohrengel and Kirsten Meyer, write only electronic letters to each other, without any folds.