On Identifying Museum Visitors and What Moves Them

The ten-millionth visitor Paula Konga in November 2015 © Jewish Museum Berlin, photo: Svea Pietschmann

Gleeful excitement in the museum lobby, for we are greeting our ten-millionth visitor since the opening in 2001, and we are all ears. “It’s my day off and I want to take the opportunity to revisit the permanent exhibition,” the 33-year-old Berliner Paula Konga tells us. An architect by profession, she is particularly interested in Daniel Libeskind’s design of the museum. “The building is well worth visiting more than once, also for Berliners.” No sooner have we handed over a bouquet of flowers and a one-year-membership in the Friends of the Jewish Museum Berlin Association than our guest of honor vanishes into the ramified spaces of the Libeskind Building (further information about the Libeskind Building can be found on our website).

Next, a group of Italian schoolchildren pushes past me, another museum visitor asks me to switch his audio guide to French, and a group of British teenagers mills about in search of a young man in a red cap. The seething mass sets me thinking: What actually moves you here, in the Jewish Museum Berlin? Is it really first and foremost the striking architecture? Happily, to pursue these and similar questions is part and parcel of my work at the museum, since I am employed in the department of Visitor Research and Evaluation. We regularly conduct studies and surveys in order to assess how effectively we are putting our message across, i.e. how successfully we communicate our thematic content to a variety of target groups.

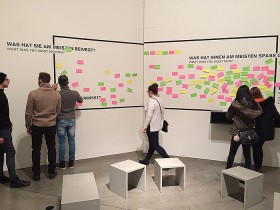

Visitors in front of the new designed wall for sticky notes

Jewish Museum Berlin CC-BY Alexa Kürth

In my mind’s eye appears an innovation in place at the end of the permanent exhibition since March 2015: in addition to the traditional visitors’ book, we provide sticky notes as a new means of making comments. Beneath the three questions “What was the most moving?”—”What was the most fun?”— “What was lacking?” visitors can post their responses on the wall.

The feedback is prolific. On average we find more than 150 sticky notes daily, as opposed to “only” 50 comments in the visitors’ book. I decide to take a look at 1000 sticky notes and 1000 visitors’ book entries, to find out what moves our museum visitors—and I am filled with curiosity.

Viewing and sorting the huge quantity of colorful notes instantly reveals how important it is to many of our visitors to immortalize themselves with a signature. This is apparent above all from the visitors’ book, in which over half the entries consist of a signature alone. This is the case in only 15% of the sticky notes, however. So far so good—now, what’s next? The content of the sticky notes is personal, expressive and direct. It most frequently concerns either Menashe Kadishman’s installation “Shalekhet” (Hebrew for “Fallen Leaves”), or the “Holocaust Tower,” or the pomegranate tree at the start of the permanent exhibition; and it takes the form of written comments or drawings.

Our visitors leave about 120 sticky notes per day

Jewish Museum Berlin CC-BY Alexa Kürth

It is likewise quickly apparent that a tour of the museum prompts our visitors to face up to and reflect on the crimes of the Nazi era (an outcome that naturally delights us). This is attested by the thoughts, appeals, and expressions of hope or gratitude made on sticky notes or in the visitors’ book, where one finds, for example: “Die menschliche Geschichte ist ein Schreck … Nicht vergessen, um zu vermeiden, dass die gleichen Fehler wieder gemacht werden.” (The history of mankind is a horror… Let us never forget, lest the same mistakes be repeated.) or “Ich danke Ihnen für die umfassende Information, auch wenn es kaum zu ertragen ist […].” (I thank you for this detailed information, even though it is difficult to bear […].). Visitors’ comments also call for peaceful, respectful co-existence, and equal rights: “Lasst uns friedvoll und in Demokratie zusammenleben! Was für ein eindrucksvolles Museum!” (Let’s live together in peace and democracy! What an impressive museum!), “Questo museo dà la consapevolezza di esistere – Riflessione” (This museum gives us an awareness of life—reflection); “Vive la paix de tous les peuples” (Long live peace for all peoples); “لا للعنصريّة لا للإرهاب” (Say no to racism! Say no to terrorism!); “We are all One;” and “One day, hopefully, there will be freedom for all.” It is striking not only how frequently, but also in how many different languages such positions are expressed.

It is evident from the entries in our visitors’ book that Menashe Kadishman’s installation “Schalechet—Fallen Leaves” leaves a lasting impression.

Photo: Alexa Kürth

The new project sparked my curiosity and I found myself wondering, in conclusion, which age groups prefer which mode of comment making, the sticky notes or the visitors’ book. I thereupon spent several hours observing visitors in this area of the exhibition—this, too, is occasionally a part of my work in visitor evaluation. It was evident that the traditional visitors’ book appeals mainly to visitors aged 40+. The younger age group of 17 to 25-year-olds tends to prefer sticky notes, reaching for a note and ballpoint pen to “post” their impressions of the museum in the classically analog manner.

Alexa Stahr is delighted by the varied feedback expressed in writing and drawings, for it provides museum staff with invaluable information. She gladly takes this opportunity to thank all past and future authors of sticky notes and visitors’ book entries.