An Early April Fool’s Joke from the Year 1931

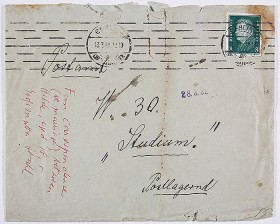

Envelope posted 13 March 1931; Jewish Museum Berlin, Gift of Margaret Littman and Susan Wolkowicz, the daughters of Hilde Gabriel née Salomonis

Sometimes figuring out how to classify a document correctly according to its historical context can depend on just one tiny, even seemingly unrelated detail. I was reminded of this again while working on the inventory of a recent donation to our archive. With more than 3,000 documents, photographs, and objects, the Gabriel-Salomonis family collection includes among other things an extensive correspondence. This consists of letters, postcards, and even telegrams, and as I sorted through these items, I came across an exchange of four letters from the early spring of 1931. Two were handwritten: composed and signed, quite legibly, by the then 72-year-old, Berlin resident Ernestine Stahl (1858–1933). The author of the other two type-written letters was at first uncertain, not least because his signature was missing. Ernestine Stahl addressed him in her replies only as “Sir” and “Dear Sir.”

I was able to solve this little riddle, however, by looking at an envelope that turned up elsewhere of the bundle of papers but appeared to belong to this brief exchange. The sender – like the memorandum added later, “Fun correspondence (re marriage) between Hilde, aged 18, & Großmutter Stahl” – showed that these letters hadn’t originated from an anonymous gentleman but rather from the young Hilde Salomonis (1912–1991), who in March of 1931 had sent her grandmother a (rather premature) April Fool’s letter as a joke!

Ernestine Stahl (2nd row, 4th from left) on her 70th birthday, celebrating with family, including Hilde Salomonis (1st row, 1st from right). Berlin, 21. September 1928; Jewish Museum Berlin, Gift of Margaret Littman and Susan Wolkowicz, the daughters of Hilde Gabriel née Salomonis

The daughter of well-to-do Berlin businessman Felix Salomonis and his wife Rosalie (née Stahl), Hilde came from a respectable family. On 17 February 1931, three and a half weeks before she wrote the first letter, she had finished her high school exams at the Bismarck Gymnasium in the prosperous Grunewald district of Berlin. In the remarks attached to her high school diploma it says that she wanted to “study political economy.” She gave up this intention, however, when she enrolled on 10 April at the University Berlin Law School, a course of study she later continued in Heidelberg, Freiburg and – after the National Socialists took power – in Switzerland, where she graduated in 1935.

Salomonis’s grandmother clearly had reservations about Hilde’s career plans. She would rather have seen her granddaughter married than at college. It was against this backdrop that Hilde Salomonis began the correspondence with her grandmother, taking the role herself of an “anonymous (male) friend” of the Stahl family writing to extol the merits of a young candidate for Hilde’s hand in marriage. The anonymous letter-writer concurred wholeheartedly with Ernestine Stahl’s conservative (as perceived by her granddaughter) opinions. He identified high school graduation as the “appropriate moment to marry off your granddaughter.”

Detail from the anonymous letter: “Dear Madam!”; Jewish Museum Berlin, Gift of Margaret Littman and Susan Wolkowicz, the daughters of Hilde Gabriel née Salomonis

It is unfortunate, however, he continued, that “young girls today” want not only to study but also to have careers, even when they are not “in pecuniary need” of them. This newfangled attitude was incomprehensible to him, he wrote. Young women had better ought to “cultivate their womanly abilities and not waste their best years pursuing masculinizing study and career training!” Since they lack the necessary life experience one could not expect them to make the choice of a marriage partner themselves. For that reason the (presumed) gentleman offered his services: he knew, he claimed, a “young friend, who would be the very person, in terms of his character as well as financially.” He comes “from a top-tier, cultivated, Jewish family, himself of independent means and elevated status.” Since the matter required discretion, any reply must be addressed to the given post office box.

Detail from Ernestine Stahl’s letter: “Dear Sir!”; Jewish Museum Berlin, Gift of Margaret Littman and Susan Wolkowicz, the daughters of Hilde Gabriel née Salomonis

In a first draft, Ernestine Stahl wrote a letter expressing enthusiasm for the offer of this unknown gentleman, who had assured her that he was simply “speaking from the heart.” She did not send this version, though. Perhaps she doubted the seriousness of his “hopefully sincerely-meant words.” Instead, on the same day, Stahl wrote a second letter in which she explained that she would not be needing the – surely “well-intentioned” – services of the letter-writer, because “my granddaughter possesses such a clear and mature character that she can certainly choose a worthy life partner for herself, without the intervention of a third party, even her grandmother.”

Ernestine Stahl on her 70th birthday (detail); Jewish Museum Berlin, Gift of Margaret Littman and Susan Wolkowicz, the daughters of Hilde Gabriel née Salomonis

Hilde Salomonis had not expected this straightforward avowal from her grandmother. She wrote another letter on 15 March in which she registered her “great esteem.” Knowing well that her grandmother actually advocated traditional conservative ideas, Hilde wrote: “it is tremendously impressive to me, dear gracious lady, that you uphold your admirable, time-tested views without imposing them on the young people.” The fact that, as family matriarch (already many years a widow), she “did not” interfere “unsolicited in the lives of her children and grandchildren” prompted the 18-year-old finally to offer a compliment: “You are more modern than our modern youth, for you are tolerant!” Hilde concluded with a proposal to meet in person, in order to “air out the cloak of anonymity:” she would make an appearance as “the good, old family friend” and no longer as “the ‘matchmaker’!” Whether or not this encounter took place and how Ernestine Stahl reacted to her granddaughter’s practical joke are unfortunately not revealed to us by the documents.

Driver’s license photograph of Hilde Salomonis, about April 1932; Jewish Museum Berlin, Gift of Margaret Littman and Susan Wolkowicz, the daughters of Hilde Gabriel née Salomonis

Hilde Salomonis did eventually get married in 1938. She emigrated in the same year together with her husband, Kurt Gabriel, to New Zealand. An autobiographical interview she gave in 1986 offered a glimpse into the mindset of this emancipated woman. In her informative and remarkably witty statements, she spoke with astonishing openness about personal matters like falling in love and sexuality in her youth, marriage and child-bearing. Sadly she doesn’t mention the exchange of letters with her grandmother, but she does relate other anecdotes. She was firmly dedicated even as a child to the idea of studying and having a career: “When I told my family that I wanted to study law, it was as if I’d said that tomorrow it will rain. Nothing special.” No one had assumed that “I would be sitting at home as a housewife.” In their social circles no one had arranged marriages. The old saying “that a father says to his daughter: ‘Come here, my child, you are the lucky bride’” was “already a joke when I was a kid.” The transcript of the interview is among the papers in the family collection and can be seen – in addition to the letters – in our Reading Room in the W. Michael Blumenthal Academy (further information on the Reading Room on our website).

Jörg Waßmer feels honored as an archive employee to be able to read private correspondence, which is, of course, not actually intended for him.