Nina Wilkens contemplating the collage “Found objects on flat cardboard box” on her computer screen; Jewish Museum Berlin, photo: Svenja Kutscher

Five black and white photographs of a scantily-clad woman, legs spread open, in various suggestive poses. The pictures smudged and stuck askew onto white cardboard. On top, a Star of David partly smeared with yellow paint. A brown dildo is fastened next to the cardboard. This constellation of things looks at first glance like useless trash. Objects left on the ground, covered with their share of grime, and now lying here piled on top of one another. This work by Boris Lurie from our current exhibition “No Compromises! The Art of Boris Lurie” (further information about the exhibition on our website) has no name and its date is ambiguous.

When I started thinking, around a year ago, about a pedagogical program on Boris Lurie, I got stuck on this picture as I sat at my computer clicking through images of the works that were being considered for the exhibit. I was confused by my own reaction to this collage of two- and three-dimensional objects: vacillating between disgust and uncertainty. I had the words “obscene” and “tasteless” on the tip of my tongue but found them unsuitable. The image hurt. I wondered how students would react to Boris Lurie’s art. Based on my own experience I quickly realized that we would need to find a way to talk together with groups of visitors about the pictures. We would need a bridge, but what could it be?

Our exhibit includes works by Boris Lurie from the 1950s to the 1970s. This was during the Cold War. Lurie had survived the Shoah, emigrated to the USA, and encountered a society that looked on that event as one among many. His works cry out with rage and despair about both what had happened and American post-war society’s insufficient examination of it: we see this in the word “NO”, which dominates his art, as well as in combinations of motifs, his choice of materials, and the way he works with them. The more one learns about his life, the more accessible his art becomes.

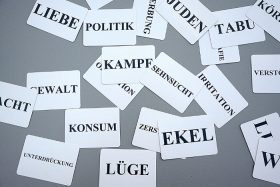

When we work with groups, our goal is to enable visitors to find their own approach, to the effect that they talk about the images. Our “bridge” is a kind of card game. On each card is a term, such as RAGE, LONGING, POWER, PAIN, or MARKET. There are also blank cards that visitors can fill in with their own concepts.

Before drawing the cards it’s essential to learn something about Boris Lurie as a person and as an artist. Then we introduce individual artworks. Up to this point our students are usually hesitant to say anything about the art. Now, though, after getting to know Lurie’s life and work, they pull a word-card from the deck. Divided into small groups, their assignment is to search for a picture or sculpture that fits the term they have. Participants move freely around the exhibit guided by the word on their card. When they choose an artwork, they then present it. Basing their discussion on the term eases talking about the art, since the word on the card is there to initiate their own statement: the term is the bridge to speaking.

A group visiting the exhibit, in front of Boris Lurie’s work “Untitled”; Jewish Museum Berlin, photo: Svenja Kutscher

Today a school class is visiting: a small group draws the word “lust” and finds a photograph modified by Lurie. The picture does not, in their eyes, elicit sexual desire but that appears to have been its original intent. The photo shows a woman reaching inside her panties with her hand and covering her private parts. The original picture is, according to this group of students, the most erotic in the exhibit. Lurie embedded the woman in white shredded paper, making her face unrecognizable. His modification causes her breasts, however, to stand out even more. The group discusses the contradictions in the picture and whether it is sexist.

A group at the exhibit with an image from the series “Dismembered Women”; Jewish Museum Berlin, photo: Svenja Kutscher

Another group writes the word “reduction” on a blank card and chooses for it a picture in the series “Dismembered Women.” They decide on that word because the bodies of the women in the series were reduced to severed, individual parts. At the same time, these parts are extremely fat. Here too they find a contradiction: between the excess of the bodies and their dismemberment. Yet another group discusses the availability of women’s bodies and the existence of brothels in concentration camps. They talk about the ambivalence provoked by the combination of bodies, their commodity status, and violence. They wonder whether Lurie took pleasure in the pornographic images.

And what happens with their own gaze? Still unsure how they want to judge Lurie’s work, the students are happily surprised by the visit, because the art is so current and political. And because they were able to encounter the art through conversation.

Nina Wilkens thanks the visitors for their statements as well as the exhibition guides for their support.

Further information about the pedagogical program on the “No Compromises! The Art of Boris Lurie” exhibition on our website for kids, students and teachers.