“Something happened there to which we cannot reconcile ourselves. None of us ever can,” said Hannah Arendt with regard to Auschwitz and its repercussions during a now legendary TV interview with Günter Gaus. A two-minute excerpt from that encounter serves today in our permanent exhibition as introduction to a film installation concerning the Auschwitz Trial (cf. this blog entry about the reopening of that part of the exhibition in summer 2013).

“Something happened there to which we cannot reconcile ourselves. None of us ever can,” said Hannah Arendt with regard to Auschwitz and its repercussions during a now legendary TV interview with Günter Gaus. A two-minute excerpt from that encounter serves today in our permanent exhibition as introduction to a film installation concerning the Auschwitz Trial (cf. this blog entry about the reopening of that part of the exhibition in summer 2013).

In our exhibition of the work of Fred Stein in 2013/14 we presented photographs inter alia of the political theorist Arendt herself, as you can read in our blog and on the exhibition website.

Hannah Arendt is a major influence also on contemporary artists: Alex Martinis Roe, in the work she produced for our art vending machine, “A Letter to Deutsche Post,” demanded a re-issue of the postage stamps bearing Arendt’s portrait (cf. our interview with the artist in this blog). Also, a symposium held at our museum last December drew on the work of Hannah Arendt as a springboard for discussion of the current significance of pluralism in theory and practice (cf. the topics addressed there, as listed in our events calendar).

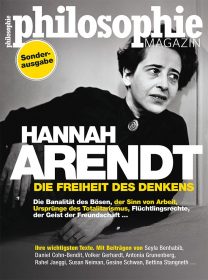

Philosophie Magazin has just devoted a special issue to this exceptional thinker. Titled Hannah Arendt. Die Freiheit des Denkens [Hannah Arendt. The Freedom of Thought], on the newsstands as of 16 June.

“Arendt’s philosophy was always political and controversial. She never evaded the public eye; in fact she regarded involvement in social and political issues as nothing less than a civic duty. […] Re-reading Arendt is not so much about blindly adopting her ideas as about striving for her ideal, which was to think in a dauntless, resolute manner, ‘without banisters,’ and without preconceptions, and to actively engage with the world we live in.”

This is how Catherine Newmark, in her editorial, summed up the intent behind this almost 150-page special issue. Important texts by not only Arendt herself but also Seyla Benhabib, Daniel Cohn-Bendit, Volker Gerhardt, Antonia Grunenberg, Rahel Jaeggi, Susan Neiman, Gesine Schwan, Bettina Stangneth, and other contemporary thinkers are compiled here under headings such as “Cerebral Relationships,” “Escape, the Jewish People, and Human Rights,” “Totalitarianism,” “Vita Activa,” “Evil,” and “Politics, Power, and the Public Realm.”

So, anyone wishing to take another look at Hannah Arendt’s work—her thoughts on the banality of evil, the meaning of labor, the origins of totalitarianism, refugees’ rights, and the spirit of friendship—should grab a copy of this magazine!

Our blog editor Mirjam Bitter, when watching the Gaus interview, was struck not only by the precision of Hannah Arendt’s analysis and language but also by how long a TV slot was devoted back then to intellectual inquiry, as well as by the choreographic dimension of the act of lighting a cigarette.

The interview (in German, with English subtitles) can be seen in full on YouTube: