A Photo Collection Found Hiding in Berlin-Friedrichshain

Every time I open a new folder of photos, I can’t know what’s waiting for me – what faces I’ll find or fates will be revealed. Images are often part of a larger collection, consisting of documents, everyday articles and artwork, for which we already know the biographies of those pictured or can further research. Such was the case, for example, of the cabaret artist, Olga Irén Fröhlich, whom I’ve written about before on this blog. This time, however, the people in the photographs will remain unknown to me; I won’t be able to attach names or histories to them. Perhaps you can!

It’s not out of the ordinary to work with collections that have been in the Museum’s possession for decades. A continuous stream of items comes to us by way of gifts and acquisition. In parallel, we endeavor to better inventory and process the items we’ve had for a long time. Doing so makes sense, as research possibilities both online and within the literature field have diversified many fold in the last 10–15 years, for example. The basis of my research always requires clues such as names, places, biographical data and relationship details among the people pictured. This vital information is largely missing from these 22 black-and-white photos. Even how they came into our collection is unusual:

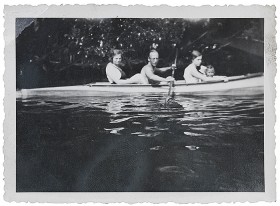

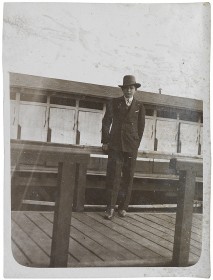

The images were discovered by sheer coincidence under the floorboards of an apartment at Simplonstrasse 19 in Berlin-Friedrichshain and turned over to the Berlin Museum in 1996, whose Jewish department became the Jewish Museum Berlin in 1999 (further information about the history of the Museum on our website). The photo collection is dated to between 1918 and 1945, and consists of passport photos, portraits and snapshots of leisure activities. The latter show a family on a nature excursion, youths at Freibad Treptow and a girl in a Berlin apartment. My efforts to come up with names of those pictured have so far yielded nothing useful. Their biographies remain a mystery – precisely the information we use to attach a Jewish context to many of our collections. The images themselves rarely give any indication of religion.

What to do with a collection whose origins we know practically nothing about? In publishing the images online, we hope the users of our online collections can shed more light on those who lived in the building on Simplonstrasse and the people portrayed in the images. And what happens when that doesn’t come to pass and the origins of the photographs remain unclear? Can they still hold some relevance for our Museum? I think so!

It’s interesting that the finder of the photos assumed a Jewish context, although the images themselves offer no concrete Jewish connection. That they were hidden under floorboards and the handwritten dates on the back of the images continue only until 1933 suggest they may have been left behind by those escaping the Nazi regime. Today, they testify to the existence of these people, and it is our Museum’s mission to safeguard what few traces of their lives we have.

Anna Rosemann hopes to learn more about the photographs and that this article can encourage other museums to find new ways to learn about their own objects with unknown origins.

All photographs found hiding at Simplonstrasse 19 are available on our German language online collections.