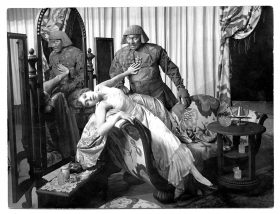

In the light comedy The Golem and the Dancing Girl from 1917, Paul Wegener satirizes his own 1915 film The Golem; photo: Deutsches Filminstitut, Frankfurt a. M./estate Paul Wegener – collection Kai Möller

In January of 1915 the figure of a golem appeared for the first time on the silver screen, on Berlin’s Kurfürstendamm. The public was captivated by a truly modern monster. At the same time, southeast of the Belgian city of Ypres battles of the First World War were raging. Following on the heels of this first silent golem movie came two more in 1917 and 1920, also debuting in Berlin. The lead role of the golem was played in all of them by Paul Wegener, who had also come up with the idea for the projects and written the screenplays.

In the current exhibition GOLEM (more on www.jmberlin.de/en/golem), a theme room has been dedicated to these three silent movies. Thanks to fantastic loans, we were able to bring together trenchant film selections, great photographs of the making of the films, expressive posters, and set designs. We weren’t always able to tell beforehand how the individual exhibits we’d selected would relate to one another and what effect those connections would have. We could only see and experience some relationships once all the original pieces had arrived and been installed.

View of the exhibition space dedicated to the theme “Horror and Magic;” Jewish Museum Berlin, photo: Yves Sucksdorff

It was clear to us from the beginning, however, that a certain image would turn up again and again in the room: the clear-cut face of Paul Wegener as it appears in all three films, crowned by a rigid, helmet-like “Prince Ironheart” headdress. With this wig on, Wegener lent the legendary Jewish figure his face as no other film actor has. This image was projected across the world through the modern mass medium of cinema, remaining present even till today. Through active branding efforts, Wegener himself contributed to the success of his golem face’s commercial exploitation: whether on visiting cards or letterhead, everything was decorated with that one emblem, which kept getting updated with the times.

These advertising cards and letterhead with Wegener’s golem head can be found in the Deutsches Filminstitut in Frankfurt a. M.

From the first film Wegener had a mannequin body double for dangerous scenes. A fascinating photograph from 1915 that we show in the exhibition reveals the two golems side by side. Looking closer at the original picture I actually noticed an eye-catching difference between the two allegedly identical golems. Do you see it too?

Paul Wegener posing in his golem costume next to his puppet double for the first golem film from 1915; photo: Deutsches Filminstitut, Frankfurt a. M./estate Paul Wegener – collection Kai Möller

While the actor bears the animating star on his chest, the mannequin is missing it. In the photo you can tell what a fantastic costume it was, designed by the expressionist sculptor Rudolph Belling and worn by Wegener in all three movies. The golem costume reminds me of monumental sandstone statuary of knights — the Roland statues that medieval towns displayed to indicate their privileges and that you can still see in old European cities, in the main square or at city hall. These Rolands were symbolic defenders of the cities’ rights and thus of their freedom. That fits well to the protector role of the golem. But to embed the Christian image of a medieval knight into this mystical Jewish context, the tunic Wegener wears in the film was embroidered with all kinds of imaginary Hebrew-ish letters as well as suggestive cosmological, occult signs — which, however, don’t have any meaning.

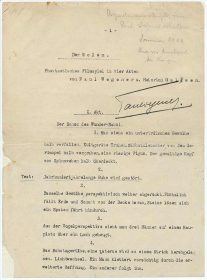

Paul Wegener’s handwritten notes on the first page of his golem film screenplay; Paul Wegener/Henrik Galeen: Der Golem, Berlin, 1914, typescript, Inv.Nr.: V 70/1626 R,7; Stiftung Stadtmuseum Berlin

This “free approach” to the theme of Judaism (to put it positively), an approach that you can also trace in the content of the films, doesn’t have much to do with the original golem ritual of Jewish mystics or the Jewish golem legend. That was a bone of contention for Jewish writer Arnold Zweig, in his review of the films. He criticized the screenplay’s creator (Wegener) as the “clueless author” and mocked his rough misinterpretations of the Jewish material: for instance, Wegener described the animating star on the golem’s chest mistakenly as “shenn.” He apparently didn’t know that the correct Hebrew word “shem” refers to one of the names of G’d. This and other odd interpretations by Wegener are wonderfully explicated in the handwritten notes the author himself wrote in the screenplay excerpts we have.

However pieced together and questionable as to content Wegener’s films may be, he certainly created an impressive contemporary document. The films and all the related items in the exhibition reflect clearly the monstrosity of the First World War and that entire global conflagration. This leads, on the one hand, into the horror that came into the world together with the golem films. And on the other, they express the magic not only of the creation of artificial life but also of the then-brand-new, modern mass medium of film, the magic of the dream factory, of sheer unlimited creative possibilities.

The fact that the silent golem movies can continually be updated, even today, is demonstrated by the many attempts at musical accompaniment the film’s spectacular pictures have inspired. From Yiddish folk music all the way to the black metal of the experimental band Fantomas. On January 23, 2017 at 7 p.m. at the Jewish Museum Berlin, Polish artist Michał Jacaszek will accompany the 1920 golem film with electronic music (further information in our event calendar). Get your own impression of this contemporary reading of the film and experience the horror and magic of the objects in the exhibition — there’s much to discover!

Anna-Carolin Augustin would like to put the golem wig from 1915 on her own head, just to find out how heavy it actually is.

The exhibition runs through January 29. Find out more at: https://www.jmberlin.de/en/golem