– The Story of a Search

This oil sketch entitled Das Gastmahl der Familie Mosse (The Mosse Family Banquet) was restituted to the community of heirs of Felicia Lachmann-Mosse; Photo: Jewish Museum Berlin, Jens Ziehe.

Today is the International Holocaust Remembrance Day when we also remember the consequences of the criminal Nazi regime, which can still be felt today. One of these consequences is that a lot of museums are still holding cultural artifacts that were unlawfully confiscated from their owners during the Nazi era. Thus the Jewish Museum Berlin restored the oil sketch Das Gastmahl der Familie Mosse (The Mosse Family Banquet) to the heirs of Felicia Lachmann-Mosse in December last year. How was this decision reached? Provenance research has attracted increasing attention in recent years and caused frequent rumblings in the media – but how is it actually carried out?

In general, the question is whether or not a work of art (or a book or other cultural artifact) changed hands during the Nazi era, whether it was unlawfully confiscated i.e. expropriated or underwent a forced sale. Should this be the case, the German museums, libraries, and archives have committed to return the artifact to its rightful heirs.

Photograph of the damaged wall painting by Anton von Werner from 1899 in the dining room of Mosse Palace at Leipziger Platz 15; Berlin University of the Arts

Since April 2015, I have been researching the history of paintings and sculptures from the collection at the Jewish Museum. One of the first art works that received my extensive attention is The Mosse Family Banquet, a sketch painted on canvas by the Berlin painter Anton von Werner. It was a preparatory work for a monumental mural commissioned by the Berlin publisher Rudolf Mosse in 1899. The original measuring two-and-a-half by five meters was so large that it covered the entire wall length. The painting found its home in the dining room of the so-called Mosse Palace at Leipziger Platz, a bourgeois town house that Rudolf Mosse bought in the 1880s and rebuilt to his taste. Rudolf Mosses art collection was on display in the mansion’s private and reception rooms – it had been accessible to visitors since the early 20th century and was often mentioned in publications of the time.

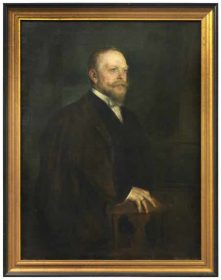

Portrait of Rudolf Mosse (1843–1920) by Franz von Lenbach, oil on canvas, 1898; Jewish Museum Berlin, gift of George L. Mosse, photo: Jens Ziehe – more on the object in our online collections (in German)

This art collection was auctioned at two Berlin auction houses in 1934. At the time the owners, Felicia Lachmann-Mosse, Rudolf Mosse’s daughter, her husband Hans and their three children had already fled Germany over a year earlier and were living in Switzerland, France, and England. After the war broke out, the family immigrated further afield to the USA. The family was able to save parts of the art collections from the family’s three prestigious residences and take them with them into immigration or have them sent on. The majority of the collection, however, was expropriated, sold, and scattered to the winds.

Tracing the paths of individual works of art is painstaking work. When I began researching the Banquet picture, the only information available was that the Berlin Museum, the predecessor of today’s Jewish Museum Berlin, had purchased it from an art trader in West Berlin in 1990. It also quickly became apparent that it was not among the paintings sold in one of the two auctions in 1934, as it is not mentioned in those catalogs.

First of all, I examined all the documents relating to the oil painting at the Jewish Museum Berlin. They showed that a descendant of the former owner had already been contacted to learn about the picture at the time of the purchase in 1990. Rudolf Mosse’s grandson, American historian George L. Mosse, could unfortunately not remember the sketch, but for that his memory of the original painting – which with its vast proportions dominated the dining room in his grandfather Rudolf Mosse’s house – was all the more vivid. The Jewish Museum Berlin repeatedly tried to learn more about the picture over the years, but these attempts always remained in vain.

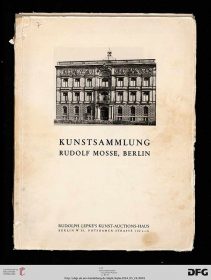

Auction catalog Lepke, May 1934; CC-BY-SA 3.0 DE Universitätsbibliothek Heidelberg. The catalog can be browsed digitally on the Heidelberg University Library website.

My next trip was to the archives to study the files. The Mosse family had tried to reclaim their property after the end of the Second World War through the Federal Republic of Germany’s restitution and reparation procedures. This resulted in a years-long struggle that produced a vast amount of files. So for several weeks I pored over these in Berlin’s regional archive (Landesarchiv) and in various other authorities that had dealt with restitution and reparation in Berlin, but the Banquet sketch was not mentioned anywhere. I also tried to find traces of the picture in catalogs, contemporary literature, and in art and image databases. All in vain.

It is not at all unusual for provenance research to be laborious and unsuccessful and it is only in the rarest cases that a look at the relevant databases or on the back of a painting is sufficient to learn who the previous owner was and under what circumstances he/she lost it.

I found first clues about the Banquet sketch at the Jewish Museum Berlin in a collection of letters entitled “Mosse Estate” from prominent personalities to Rudolf Mosse and his wife Emilie. In one of the letters, the commissioned painter Anton von Werner wrote that he had delivered the sketches to the client. And in the Leo Baeck Institute’s online collection, there is a catalog of Rudolf Mosse’s art collection in which the sketch is mentioned. However, I only came across the crucial evidence in the archive of the art dealer Karl Haberstock, who was commissioned to auction the Mosse art collection. It was there that I found a list of price estimates that the art works to be auctioned in spring 1934 might fetch and on this list – created in August 1933 in preparation for the auction – is the Banquet sketch. Even though there is no evidence that it was sold at one of the two mandatory auctions, it is nonetheless proof that the picture was in that Berlin house at a time when the Mosse family had already left Germany. Thus, the family no longer had control over the picture nor had it received any sales proceeds. According to the guidelines of the federal government, states and municipalities in Germany, a persecution-induced dispossession is thus to be assumed.

That is why the Jewish Museum Berlin decided to restore the oil sketch of the The Mosse Family Banquet to Felicia Lachmann-Mosse’s heirs. The community of heirs, as rightful owner, consented to leaving the picture in the museum for a year as a loan. Thus it can continue to be admired as before in the permanent exhibition of the Jewish Museum Berlin (further information on the permanent exhibition).

Heike Krokowski likes looking on the back of paintings.