A Newly Acquired Passover Haggadah and Its Previous Owners in Kreuzberg

Next week, the first Passover Seder will be celebrated on the evening of April 14. All over the world Jews will gather with their family and friends around festively decked tables and partake in the centuries-old tradition of reciting the Haggadah. Its text describes the story of the Israelites’ liberation from slavery in Ancient Egypt and sets forth the order of the evening.

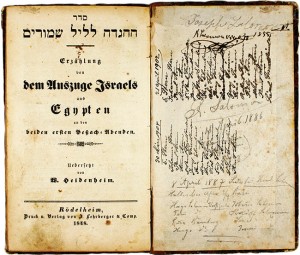

“An Account of Israel’s Exodus from Egypt on the First Two Evenings of Passover,” published in Rödelheim near Frankfurt, 1848

© Jewish Museum Berlin, photo: Aubrey Pomerance

A Haggadah in an online auction recently caught my eye, and I managed to purchase it for a negligible sum for the Jewish Museum Berlin. Published in 1848 in Roedelheim near Frankfurt under the title Erzählung von dem Auszuge Israels aus Egypten an den beiden ersten Pesach-Abenden (An Account of Israel’s Exodus from Egypt on the First Two Evenings of Passover), the book contains the Hebrew version of the Haggadah text, along with its translation into German by Wolf Heidenheim. It is the twentieth edition of the Roedelheimer Haggadah that first appeared in 1822/23, there with the German translation in Hebrew characters. In 1839, the translation first appeared in Roman letters, as is the case with our new acquisition.

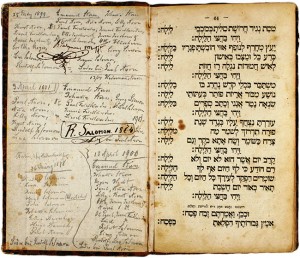

There is, to be sure, nothing remarkable about this edition from 1848. In contrast to so many Haggadot, it contains no illustrations, which for so many people provide the incentive for creating their own collections. It offers neither a fancy typography, nor commentaries, nor any other special features. The book is not even complete, since the last fifteen pages are missing. It is thus certainly not on account of any formal qualities that our Haggadah holds such allure, but rather due to the handwritten lists which are found on both inside flaps of the book.

These notations record the names of those who attended eight Seder celebrations between the years 1886 and 1904. In and of itself, there is probably nothing exceptional about the existence of such lists, even if this Haggadah is the only one in the Museum’s collection to contain such entries. Yet for us, the most striking fact is that the persons named here celebrated Passover together in the immediate vicinity of the Museum, namely on Hallesches Ufer (a road running along the Landwehr Canal) and in the Hedemannstraße.

Through further research and with the assistance of my colleague Barbara Welker from the Centrum Judaicum, who was able to supply data on burials in the Jewish cemetery at Berlin-Weissensee, it proved possible to more closely identify the majority of the individuals whose names appear in the book. It turns out that we are essentially dealing with three related families, the Arons, the Salomons, and the Sterns. The first owner of our Haggadah was Joseph Salomon, born in 1818 in Nickenich in the Rhineland. He later gave the book to his son Rudolph, who was born in Aachen in 1848 and who later became co-owner of a mechanical tricot weaving manufactory in Berlin. From 1886 to 1888, the Seders were celebrated in the apartment at Hallesches Ufer 3/4, where Rudolph lived with his wife Lina née Stern, a native of Siegburg. From 1899 to 1901, and probably also in 1902 and 1904, the families gathered for the celebration in the Hedemannstraße 13/14, the home of their niece Anna Aron and her husband Paul. Assembled at the Seder were Anna Aron’s parents, siblings and children, some of Rudolph Salomon’s siblings, and further relatives and friends, some of whom lived very close by. Alongside the basic biographical data of many of the people named in the lists, details of the tragic destinies of certain individuals were also revealed: Anna Aron was deported and murdered in Theresienstadt in 1942, and her son, school inspector Dr. Kurt Aron, in Auschwitz that same year.

The fate of the Haggadah itself up until its appearance in an online auction will doubtless remain open to conjecture. It is clear, however, that it served the families not only as a book of remembrance of the Exodus from Egypt, but also as a personal keepsake of shared memories that now opens a small window onto their histories. That it will be preserved in a place so close to the apartments where it was read at Passover Seders more than one hundred years ago is a most fortunate coincidence. Further research will hopefully bring additional knowledge to light—and ideally lead to contact with the families’ descendants.

Aubrey Pomerance, Director of Archives