Five stamp-sized advertisements for the company Otto Klausner GmbH, Berlin, ca. 1910-1914. Gift of Peter-Hannes Lehmann

Like every museum, we have some objects in our collection that are always on display for our visitors, some that we show from time to time in temporary exhibitions, and also some that we rarely show because they are more suited to research purposes. And then there are objects that we should have put on view long ago but they are still sitting, out of sight, in our warehouse. It affords a particular pleasure when such items finally get processed for our online database and put on display.

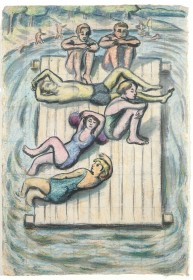

A collection that falls into this category is a set of graphics by Leo Prochownik (1875 – 1936) that his daughter, Marianne Krausz, gave us in the run-up to the Jewish Museum’s opening in 2000. Prochownik, who pursued his artistic training through sheer obstinacy, despite the opposition of his father, was not a famous artist. While his better known contemporaries were plunging into the world of abstraction and experimentation, he remained committed to depicting the naturalistic world around him (even while he occasionally ventured into Biblical-themed territory). “He always felt the need to paint from nature, the way someone who doesn’t yet know how to swim won’t dare to go out into the open water,” explained his wife Gertrud Prochownik (1884 – 1982).

His early works are strongly influenced by Jugendstil and he published drawings during this period in artistic magazines such as “Die Jugend” (The Youth) and “Pan.” The First World War caused a caesura in Prochownik’s life: after the war broke out, he began to draw people on the streets of Berlin – “the people who stood in front of newspaper kiosks and studied the war reports and lists of the dead with anxious faces” (Gertrud Prochownik). In 1917 he was drafted into the military but he couldn’t bear the psychological strain for long. During his stay in that same year at the auxiliary military hospital in Kortau he produced more portrait studies. Back in Berlin, he recovered slowly.

Beach scene, pastel, ink, brush on Japanese paper, ca. 1920-1936. Gift of Marianne Krausz, née Prochownik

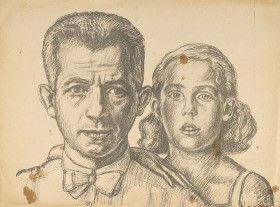

Gertrud Prochownik took over the role of breadwinner for the family, starting a job at the Berlin city employment agency in 1917, and moving, in 1920, a year after the birth of her daughter, to the provincial employment office’s department of women’s affairs. Ultimately she took over the Jewish employment agency in 1925. Despite some minor artistic successes after the war, Leo Prochownik was somewhat intellectually isolated, but through his wife’s professional contacts he encountered new circles of people. For a book project (that, however, didn’t come to fruition) he began to create portraits of young people who were preparing for the aliya, the emigration to Palestine.

Self portrait of the artist with his daughter, lithograph, ca. 1930-1932. Gift of Marianne Krausz, née Prochownik.

In December of 1936 shortly before the exhibition, which was to be shown at the Jewish Women’s Home of Berlin, opened, Leo Prochownik died. While his daughter Marianne was able to emigrate to England in 1939, Gertrud Prochownik remained in Berlin where she survived in hiding. For a time she believed her husband’s works to have been lost, but they were in fact rescued and eventually returned to the family after the war.

After Marianne Krausz gave the museum her father’s drawings, we put an appeal in the emigrant magazine “Aktuell” to try to locate people whom Prochownik had drawn. Since he hadn’t provided names for the portraits, it was a difficult proposition, but we were able to identify a few of them after all: among others, the portrait of Klaus Mendelsohn. Mendelsohn’s mother, a colleague of Gertrud, was murdered. Her son Klaus survived a number of concentration camps and left Europe after the end of the Second World War. Prochownik’s drawing is the only picture still extant from his childhood.

The inventory received an unexpected addition last year: as we were going through a huge collection of advertising stamps that had been given to us, we stumbled upon five stamps from a Berlin shoe store with the signature of “Leo Prochownik”. Those advertisements can be seen now, until the end of May, in our cabinet exhibition “Pictures Galore and Collecting Mania”. We knew that Prochownik had designed advertising posters in his early years as a professional artist, but until now none of these had been found: at last, however, we can begin to imagine what a Prochownik poster would have looked like and we hope to find more items from this part of his opus.

Iris Blochel-Dittrich, Documentation of the collections