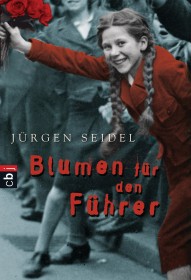

Innumerable publications have appeared on the market about the Nazi period in Germany, as well as a steady stream of new novels, non-fiction, and books for children or young adults that deal with this subject. Among them you will find Jürgen Seidel’s “Flowers for the Führer,” the first part of a trilogy that is, according to the reviews, “a very complex, moving, and exciting novel for young adults about a tragic love story during the era of National Socialism,” and is also “worth reading for adults.” Some of us read the trilogy as part of a reading group dedicated to keeping abreast of children’s and young adult literature about Nazism. And we quickly discovered that instead of discussing the depiction of the Nazi regime and German history, we needed to talk about something else: racism.

“Racism encompasses ideologies and practices based on the following construct: that groups of people are communities defined by ancestry and origin, to whom can be ascribed collective attributes that are implicitly or explicitly appraised and interpreted as unchanging or only changeable with great difficulty.” (Johannes Zerger, Was ist Rassismus? (What is Racism?), Göttingen 1997, p.81).

If you consider the questions of how to facilitate diversity and how to avoid stereotypes and hateful clichés, as many employees of the Jewish Museum do daily, then you would be perplexed at the very least to find – on the first page of a book for young adults – un-annotated and unexplained uses of words like “coal-black,” “stinking,” and “nigger boy.”

Now you might think that this is how girls must have spoken in 1936, and if the author is trying to capture the tone of that time period then he has to use the most profoundly racist language. And yet on later pages as well as in the subsequent parts of the trilogy, obviously free from any compulsion to use this kind of speech verbatim, the author has his narrator speak in terms that come directly from colonialist usage: not only does the n*-word appear page by page with no compelling narrative need, but the portrayal of Africans and African-Americans is rife with stereotypes that seem to be snatched straight out of books from the 19th century.

Again, you can argue that an omniscient narrator speaking from the perspective of his protagonist should also draw on that character’s language. But what happens then? When does borrowing from racist usage become racist itself?

At the latest, it happens when the stereotypes are left as they appear on the page, uninterrupted and unquestioned by any development in the thinking of the story’s hero or by critical reflection on the part of the narrator. This is exactly what happens in these novels: while individual terms and figures of speech from the Nazi period are explained extensively in a glossary, racist phrases, on the other hand, are not subject to any commentary, on the apparent assumption that they are self-evident and need no explanation for the lay reader.

So what happens when the narrative doesn’t provide any reflection on its own explicitly value-laden constructs? A critical reader will cringe and be surprised, offended, baffled, or appalled. An uncritical reader might simply skim over these passages without noticing much. A reader already inclined towards the right-wing, nationalist end of our society’s political spectrum will find her prejudices – including the described victimhood of purportedly innocent Germans – confirmed. All this is bad enough. But what about young readers who have never come into contact with the brutality of this kind of language? The unbroken tradition that passes racist or anti-Semitic clichés from one generation to the next achieves one thing above all: that they live on, that they spread, and unfortunately – in the case of this trilogy – that they are also seemingly validated.

Marie Naumann, Publications

A dose of realism is good. In my experience children these days have no time for people who fudge facts.

And “purportedly innocent Germans” ? As a very well known religious Jew said “Let him [or her] who is without sin cast the first stone”.

Ray.