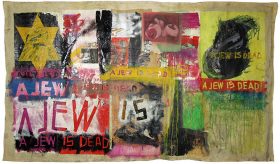

A Conversation with Peter Weibel about whether Boris Lurie Should Be Seen as a Part of the Ultra-realist Neo-avant-garde, and Pornography as a Metaphor for Capitalist Society

Mirjam Bitter, blog editor: As part of the program accompanying our Boris Lurie retrospective, you’ll be giving a lecture at the Jewish Museum Berlin on 30 May 2016 on the subject of “The Holocaust and the Problem of Visual Representation,” (further details of which can be found in our events calendar). Is this tied up with the idea that the Holocaust is a major theme in Lurie’s work?

Peter Weibel: The Holocaust, along with war, Hiroshima, and Nagasaki were pivotal traumatic experiences for the post-Second World War neo-avant-garde. Take, for example, Yves Klein’s painting “Hiroshima” (1961) or Joseph Beuy’s environment “Show Your Wound” (1974–1975). Many artists responded to the inhumanity they had witnessed by calling into question humanity and indeed, civilization itself: Why, they asked, had literature, painting, music, and philosophy been unable to prevent this twentieth-century barbarism?

By 1945, Europe had hit rock bottom, existentially and morally. Artists fell back on defensive mechanisms as a means to process traumata. One of the ego’s primary defense mechanisms, according to Anna Freud (1936), is reaction formation, namely the endeavor to neutralize a negative experience by emphatically or even exaggeratedly embracing it as a positive experience of sorts. This is why artists perpetuated the Nazis’ destruction of civilization through reaction formation, which is to say, by destroying canvases, pianos, and so forth.

Jean Tinguely’s “Homage to New York,” 17 March 1960, Museum of Modern Art

The result was a crisis of representation so radical that the auto-destruction of artistic media became a form of self-expression in its own right—as propagated in the early 1960s by Gustav Metzger, for example, or in Jean Tinguely’s “Homage to New York,” a performance piece featuring an auto-destructive sculpture (1960). This is why the Holocaust was a central theme for Boris Lurie and many other artists.

Interior view of the first room in the Jewish Museum Berlin’s Boris Lurie exhibition with works of the “Dance Hall Series,” the “Saturation paintings,” and the “Love Series;” Jewish Museum Berlin, photo: Yves Sucksdorff

Our program director Cilly Kugelmann said recently in this blog that Boris Lurie was clearly shaped by his experience of persecution and concentration camps under the Nazi regime yet cannot, in her view, be described as a “Holocaust artist.” Do you share her opinion?

PW: Yes, I agree with Cilly Kugelmann. Lurie was an artist who followed the principles of the Frankfurt School, which maintained among other things that, “Whoever is not willing to talk about capitalism should also keep quiet about fascism.” A critique of capitalism and consumer society was a pivotal theme of Lurie. The distinction is therefore valid: although the Holocaust is of major significance in his work, Lurie is not a Holocaust artist.

You describe as “ultra-realism” Boris Lurie’s response to the problem of whether art is able, post-Holocaust, to represent anything at all. Could you please explain for our readers exactly what you mean by that?

PW: One very famous response to Auschwitz came from Theodor W. Adorno: “Cultural criticism finds itself faced with the final stage of the dialectic of culture and barbarism. To write poetry after Auschwitz is barbaric. And this corrodes even the knowledge of why it has become impossible to write poetry today” (1949/1951). This statement spelled out the end of art’s capacity to represent anything, as well as a rejection of the traditional codes of art, and an iconoclastic impulse congruent with the abstract tendencies of the avant-garde.

Zyklon B container, part of an exhibition in the concentration camp Auschwitz-Birkenau; Michael Hanke, Zyklon B Container, CC BY-SA 3.0

The other side of the coin was the publication in 1960 of “Nouveau Réalisme” (New Realism), a manifesto featuring artists who exhibited real objects of everyday use. Raul Hilberg, one of the founders of Holocaust research, advocated precisely this realist position in his autobiography The Politics of Memory: Journey of a Holocaust Historian (1996). Asked how the Holocaust might be portrayed, he answered: “I would have liked to see a single can [of the Zyklon-B gas with which Jews were murdered in Auschwitz and Majdanek] mounted on a pedestal in a small room, with no other objects between the walls, as the epitome of Adolf Hitler’s Germany, just as a vase of Euphronios was shown at one time all by itself in the Metropolitan Museum of Art as one of the supreme artifacts of Greek antiquity.”

Lurie also resorted to pornography in order to portray what was, in his view, an obscene society. Was this a novel approach, in his day? Or did he thereby fall into line with a particular artistic tradition?

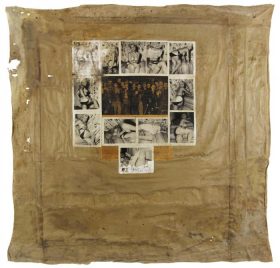

Boris Lurie, “Saturation Painting (Buchenwald),” 1959–1964; Boris Lurie Art Foundation, New York, USA

PW: It was in 1967 that universal pornography as a metaphor for capitalist society began to gain ground, following the publication of The Society of the Spectacle by Guy Debord, founder of the International Situationists, and Jean Baudrillard, who was briefly a member of that movement. In a consumer society, where (to paraphrase Oscar Wilde) nothing is of value and yet everything has its price, where the exchange value of a thing fluctuates wildly regardless of its utility value, where, in short, everything has become an object of barter, which is to say, a commodity, then there is no mistaking the pornographic moment. Lurie takes his place in this tradition, this critique, in order to portray the obscenity of a capitalist society based on credit and trade for profit.

Would you say that his artworks have a different impact now than when they were first produced? Would other artistic means be required today, to express this same radical intransigency?

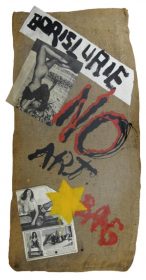

PW: In founding NO!art and declaring that all art is now inadequate to representing the inhumanity of the world, Lurie took a more extreme position than his peers did on the iconoclastic impulse of the neo-avant-garde. Analytically speaking he agreed with Adorno yet in terms of his personal response he was closer to Hilberg.

Before the realists there were the affiche-ists of course, who declared torn or slashed billboard posters to be works of art. These incidental collages of the diverse materials found in public space, from advertising for luxury goods to images of catastrophes, amounted to a public avowal of the fact that, in the eyes of the mass media, everything was of equal value yet simultaneously indifferent—be it a crime, a flower, or a consumable item.

As we know, it absolutely outraged Lurie to see magazines and newspapers juxtapose photos of the Holocaust and trivia such as bikini ads. In his collages, he simply re-contextualized the images then ubiquitous in popular media and in this respect made a re-entry (to cite Niklas Luhmann), which is to say, he consciously put a part of everyday public life back into the public eye. Lurie was a media artist who held a mirror up before the mass media: the grotesque faces, monstrousness, and obscenities that they saw in his work were a reflection of their own selves. Society too is confronted with its mirror image when it views Lurie’s “obscene” work.

I personally maintain that his artistic media are as appropriate today as they were in his own time. Moreover, given the art market’s current predominance in the media and museums, his rejection of art as a part of the capitalist system and his conviction that art is an accomplice, not a critic, of market mechanisms are even more important now than ever before.

Prof. Dr. h. c. mult. Peter Weibel is an artist and exhibition curator, and director of the ZKM Center for Art and Media in Karlsruhe, Germany.