Second Episode of our blog series: “Remembrances of the life of Walter Frankenstein”

Jesse Owens – this name means something to most people, even today. The black athlete from the U.S. national team decided in 1936, disregarding the expectations and fears of his family, friends, and a large number of Americans, to compete in the Olympics in Berlin. In light of the political climate prevailing in the place where the Olympics were to be held – where Antisemitism, propaganda, and violence against minorities were routine aspects of life, international opinion placed little stock in the chances of a fair competition among the athletes.

Exterior view of the Auerbach Jewish Orphanage, Berlin, around 1940–1944; Jewish Museum Berlin, gift of Leonie and Walter Frankenstein

For Walter Frankenstein, the name Owens was closely tied to the experience of moving from his home town of Flatow (today Złotów) in what was then West Prussia to Berlin. When he arrived by train at the Alexanderplatz station on 27 July 1936, preparations for the Summer Olympics to be held in the German capital were in full swing. Walter attended the event with an uncle on his mother’s side and thus had the opportunity to see Jesse Owens competing live in Berlin’s Olympic Stadium. Owens was the most successful male athlete of the Games, winning four gold medals.

In that summer of Olympic fever, Walter’s uncle Selmar Frankenstein entrusted him to the Baruch-Auerbach´schen Waisenerziehungsanstalten – the Auerbach Orphanage. This private orphanage, founded in 1832, cared for both boys and girls without parents. In 1897, the institution had moved into a new building that housed its own synagogue at Schönhauser Allee 162.

Kurt Gumpert running a race, Berlin, 1936–1942; Jewish Museum Berlin, gift of Leonie and Walter Frankenstein

Walter was not just a passionate fan of sporting events. He himself competed in track and field, boxing, soccer, and the German sport of handball as a member of the Jewish Club Maccabi. At the Auerbach Orphanage, as well, sports formed an important part of the school curriculum. There were regular competitions among the wards of the orphanage, but also between the Orphanage team and students of the Jewish School in Berlin’s Ryke Strasse. Walter captured moments from these sporting events – such as his friend Kurt Gumpert crossing the finish line – on film with the camera which he had been given for his birthday in 1936.

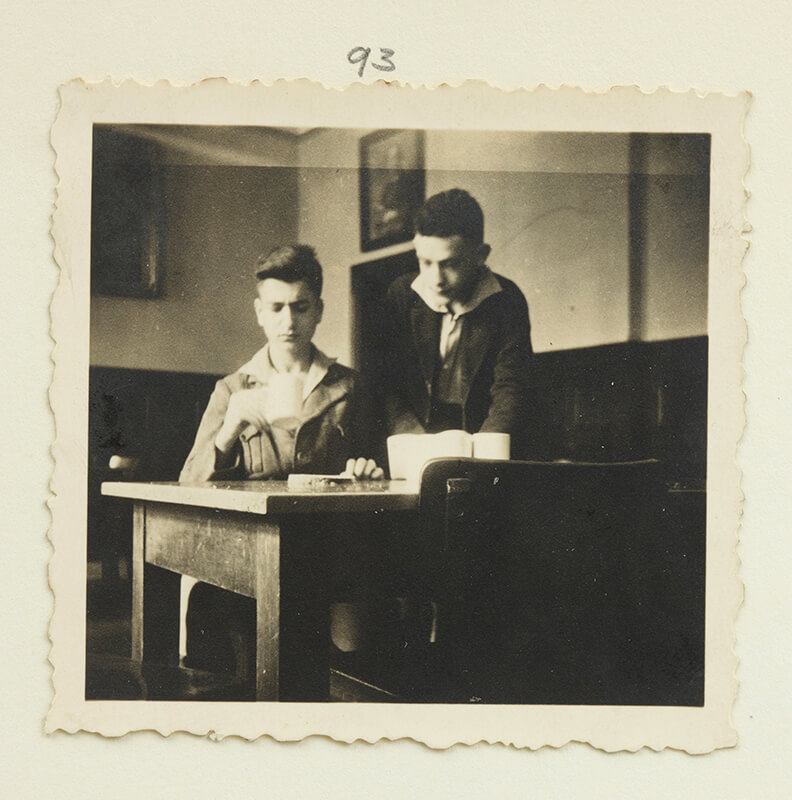

Erwin Panthauer is served rice gruel by Gerd Punscher, Berlin 1936–1938; Jewish Museum Berlin, gift of Leonie and Walter Frankenstein

Walter documented in photographs not only special events, but also the everyday life of the orphanage. Thus we can still see today how Erwin Panthauer’s face looked as he was being served rice gruel. Selma Plauts, the Orphanage Director’s wife, had ordered that gruel be served twice a week to all wards of the orphanage who looked a little “weak.” Walter, who belonged to this group, was able to get rid of the gruel by a kind of trade: Erwin ate Walter’s gruel and, as payment for that favor, also got to eat the piece of cake that Walter, like every ward of the orphanage, received on Saturday morning in celebration of Shabbat.

Up to that point in time, the Auerbach Orphanage had functioned as a refuge for 200 children and young people. Walter reports about this period: “We lived there as if on a small, sheltered island. We didn’t really have much experience with persecution until the pogrom of ‘Reichskristallnacht’ in 1938.” But on that night, a gang of plundering Nazi Storm Troopers bent on arson burst into the orphanage. Walter and three other young men tried to stop them. They insisted that there were many children and young people living in the house, and that the closely neighboring buildings could easily catch fire, too. The Storm Troopers withdrew, but as they did so blew out the Eternal Flame on the altar of the synagogue and opened the gas valve all the way. Fortunately, Walter and his friends noticed that the gas was flowing out freely and were able to prevent the worst from happening.

Afterwards, the four boys climbed onto the roof of the orphanage. From there, they could see the fires raging all over the city. A photograph of this night has not survived. But as someone who has acted as passionate caretaker for the Frankenstein collection and conducted research on Walter’s life, the mere thought of what Walter and the others must have witnessed at that moment makes me shudder.

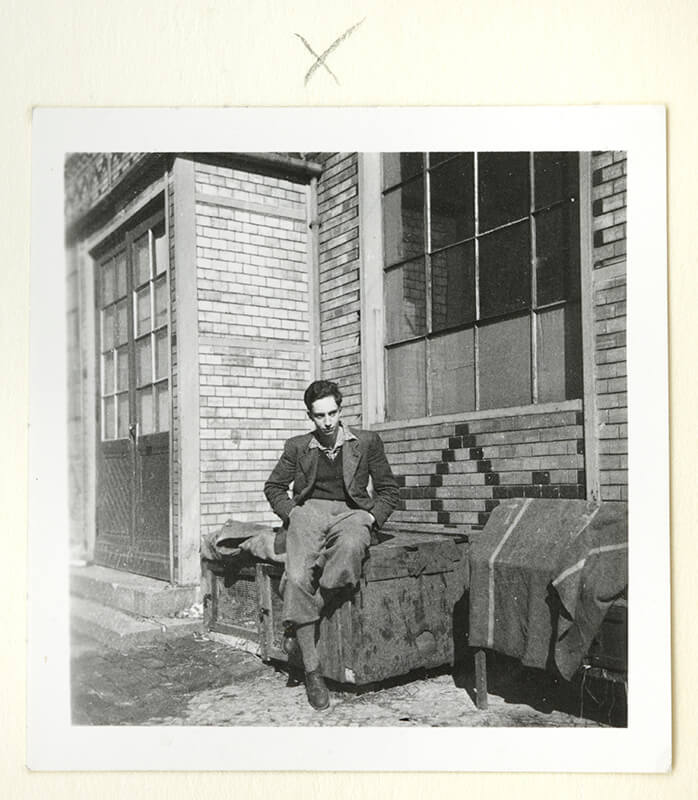

Apprentices at the Jewish Building School performing masonry work, Berlin 1938–1941; Jewish Museum Berlin, gift of Leonie and Walter Frankenstein

Walter Frankenstein in front of the gymnasium at the Jewish Orphanage, Pankow, Berlin 1938–1940; Jewish Museum Berlin, gift of Leonie and Walter Frankenstein

A short time later, Walter Frankenstein left the Auerbach Orphanage and moved into the Jewish Orphanage in Pankow. Since graduating from the Jewish Technical Secondary School in 1938, he had been training as apprentice mason at the Jewish School of Construction at the Ostbahnhof in Berlin. But his stay in Pankow proved to be a short one. The orphanage was shut down in 1940 and all the children and young people living there were sent back to the Auerbach Orphanage. Walter returned to the place where he had spent a happy youth, and where he would soon meet the woman of his life.

Given the number of photographs that have survived from Walter Frankenstein’s time in the Auerbach Orphanage, Anna Rosemann had no easy time in selecting the pictures to illustrate this text.

You will find more photographs from this and other periods in Walter Frankenstein’s life in our Online-Collections.

If you would like to delve more deeply into the biographies of Walter and Leonie Frankenstein, we recommend the book Nicht mit uns – Das Leben von Walter und Leonie Frankenstein by Klaus Hillenbrand, which was published in 2008 by the Jüdischer Verlag, an imprint of Suhrkamp.

My aunt, Ruth Reissner, who must have been a distant relative of Walter Frankenstein, was also at Pankow and at the Auerbach orphanage. Ruth’s name is on a plaque in what is now a library and a school in Pankow. Ruth was deported to Riga and killed on arrival with the children from the orphanage. I have to tried to find out what Ruth did at the orphanage but no-one seems to remember her.