Last summer, a snigger went viral in the Jewish online community when an eBay entrepreneur posted a pendant of a Navajo moose. Labeled a “Unique Vintage Navajo Moose 925 Sterling Silver Pendant, marking 0.8 grams,” the trinket for sale was in fact a Jewish amulet depicting the Hebrew word “chai” for “life/living.” The motif is popular in Jewish jewelry. It consists of the two letters chet and yod and is not commonly mistaken for an animal. But this particular example simplified the letters and joined them together, which made them appear, quite truly, like an antlered moose in Native American style.

Psalm 67 is engraved on this pendant. Amulets in shape of a hand are popular in Judaism and Islam in North Africa and in the Middle East, as well as in Eastern Christianity.

© Jüdisches Museum der Schweiz, photo: D. Hofer

Unintentional as it was, this glitch exposes the ways in which symbols and references can move from one culture to another, sometimes morphing, and generating new myths. As it appears, talismans, amulets, and charms are particularly prone to intercultural exchange. The exhibit “1001 Amulets. Protection and Magic – Faith or Superstition?” at the Jewish Museum in Basel (jointly curated with the Bibel + Orient Museum in Freiburg) presents the idea that cultures have shared, varied, and absorbed each other’s motifs for millennia. “1001” refers to the collection of stories compiled in medieval Arabic, and published under the title Arabian Nights, or, in German, 1001 Nacht.

Accordingly, many of the amulets on display have motifs common to Jewish and Arabic cultures, such as the Scarabaeus beetle or the chamsa (fatma) hand on the exhibition poster.

The back side of the scarab was retroactively engraved and worn as an amulet. Middle East, 5th-10th century

© Jüdisches Museum der Schweiz, photo: D. Hofer

In Europe, Jews and Christians traded religious iconography with one another as well. In his study on “Jewish Magic and Superstition” Joshua Trachtenberg describes a variety of Christian artifacts with Jewish motifs believed to have magical powers, such as psalm verses, or when knowledge of these was insufficient, pseudo-lettering that was supposed to look like Hebrew.

In late antiquity, zodiac wheels and other Greco-Roman signs found their way into Jewish religious houses, such as the sixth-century Beth Alpha synagogue near Beit She’an, Israel. On a mosaic floor, the constellations are ordered in circular form around an image of the sun god Helios – a representation of pagan polytheism, offending the Jewish prohibition on forming images of the divine.

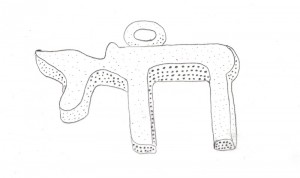

This pendant has the shape of a cross. The divine name Shaddai is engraved in Hebrew on the front, on the back the letter ה. Probably of Christian origin, 19th/20th century.

© Jüdisches Museum der Schweiz, photo: D. Hofer

Jean Seznec, a historian whose main work “The survival of the pagan gods” was published 1940, one year after Trachtenberg’s study, identified Greek and Roman gods in medieval art, some of whom acquired distinctly Christian traits, such as halos. Others received unexpected attributes. Pluto, the god of the underworld, holds a jug in his hand in a manuscript of Hrabanus Maurus, a ninth-century bishop. Seznec ascribes this unlikely vessel to a confusion of the words orca, for jug, and orcus, for realm of the dead.

In light of the history of religious exchange, it is a pity that the true identity of last year’s eBay Navajo moose was exposed. Who knows what new mythology it might have spawned?

Naomi Lubrich, Media

Very good stuff, I would like to thank you for this blog.