Fritz Scherk and the history of a family business in Berlin

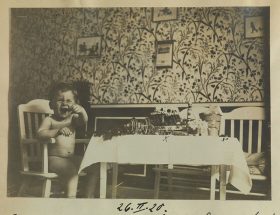

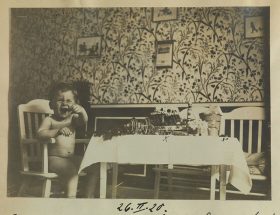

Fritz Scherk on his second birthday, Berlin, May 26, 1920; Jewish Museum Berlin, gift of Irene Alice Scherk, photo: Jens Ziehe

A beaming toddler sits naked on a lavishly laid birthday table, apparently having the time of his life. A photo like this could easily have been taken today, I thought, when I saw it in the diary that Ludwig and Alice Scherk kept for their son Fritz. In fact, the happy child would have turned 100 today. Being born in 1918 didn’t exactly promise a peaceful life, especially not for a member of a German-Jewish family. Actually the family’s second child had been planned for 1916, three years after the birth of their first son, but the outbreak of war got in the way. But on May 26, 1918, the time had come: Fritz was born next to his mother’s Bechstein piano—by candlelight because of the war, and just two minutes away from his parents’ business, the Scherk Perfumery on Kurfürstendamm. → continue reading

Five stamp-sized advertisements for the company Otto Klausner GmbH, Berlin, ca. 1910-1914. Gift of Peter-Hannes Lehmann

Like every museum, we have some objects in our collection that are always on display for our visitors, some that we show from time to time in temporary exhibitions, and also some that we rarely show because they are more suited to research purposes. And then there are objects that we should have put on view long ago but they are still sitting, out of sight, in our warehouse. It affords a particular pleasure when such items finally get processed for our online database and put on display.

A collection that falls into this category is a set of graphics by Leo Prochownik (1875 – 1936) → continue reading

Teddy bear that belonged to Ilse Jacobson (1920-2007), textile, straw, glass, ca. 1920 to 1930, in our online collection

56,250. This is the number that comes up when I search our collection’s database for its complete holdings. 56,250 data sets describing, for the most part, individual objects, and occasionally entire mixed lots. You can now see 6,300 of these objects online. Releasing this information to the public provokes mixed feelings on the part of museum staff: we have a lot to say about many of these objects. Many of them don’t speak for themselves. You can’t tell, for instance, that this teddy bear belonged to a child emigrating from Germany. The meaning of many documents and photographs lies likewise to a large extent in their biographical or political history. They require sufficient detail and well-chosen catchwords to help visitors find other objects related to the same topic.

With this project, we have to proceed pragmatically. 15-30 minutes of working time per object is a lot if you have to inventory a mixed lot with 250 units. We verify everything, including things that occur to us as we’re working. We are aware that there’s more to write about – and there would be more to correct, – if we had the time for more thorough research. Yet we can only make forays into the library or even into the archive for special projects or particularly important objects. And so we rely to a great extent on digital sources. → continue reading