An Early April Fool’s Joke from the Year 1931

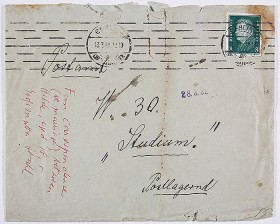

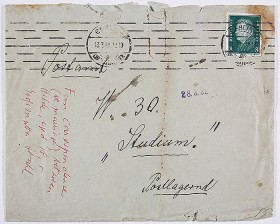

Envelope posted 13 March 1931; Jewish Museum Berlin, Gift of Margaret Littman and Susan Wolkowicz, the daughters of Hilde Gabriel née Salomonis

Sometimes figuring out how to classify a document correctly according to its historical context can depend on just one tiny, even seemingly unrelated detail. I was reminded of this again while working on the inventory of a recent donation to our archive. With more than 3,000 documents, photographs, and objects, the Gabriel-Salomonis family collection includes among other things an extensive correspondence. This consists of letters, postcards, and even telegrams, and as I sorted through these items, I came across an exchange of four letters from the early spring of 1931. Two were handwritten: composed and signed, quite legibly, by the then 72-year-old, Berlin resident Ernestine Stahl (1858–1933). The author of the other two type-written letters was at first uncertain, not least because his signature was missing. Ernestine Stahl addressed him in her replies only as “Sir” and “Dear Sir.”

I was able to solve this little riddle, however, by looking at an envelope that turned up elsewhere of the bundle of papers but appeared to belong to this brief exchange. → continue reading

Shortly after the opening of our temporary exhibition “Snip it!”, the Jewish Museum received as a bequest the estate of Fritz Wachsner (1886 – 1942). Included in this delivery was a bundle of letters so enormous that I didn’t have time, in creating an inventory, to delve into each individual piece. But one letter caught my attention. “[…] Your assessment of the circumcision issue […]”, wrote Wachsner on 24. July 1919 to his – then very pregnant – wife Paula’s uncle Anselm Schmidt (1875 – 1925). I read on and suddenly found myself in the middle of a nearly one-hundred-year-old internal Jewish debate on circumcision.

Fritz Wachsner with his wife Paula and their first-born child, Charlotte, studio portrait, ca. 1916 © Jewish Museum Berlin, photo: Jörg Waßmer, Gift of Marianne Meyerhoff

At the time, Fritz Wachsner was 33-year-old teacher in the town of Buckow in Brandenburg. In the five-page letter he clarifies the reasons for his hostile stance towards the Bris. He was an assimilated German Jew and belonged to a Reform Jewish congregation. As he explains to his uncle, he was “raised fairly orthodox” but, in the course of his university studies in Berlin and Jena as well as at the Academy for the Study of Judaism in Berlin, he learned “to know and appreciate the spirit of Judaism freed from every non-German embellishment”. He became persuaded that the religion should evolve continually and be “modernized and improved”. Wachsner’s maxim was: “Become German, outside as well as inside the religious community”, the overtones of which are especially → continue reading

A Letter from the Archive Tells of the Outbreak of War in 1914

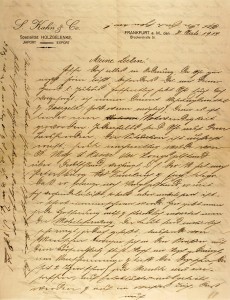

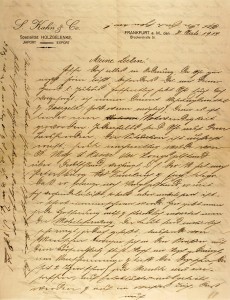

Letter from Leo Roos to his family (first page), Frankfurt am Main, 31 July1914

Donated by Walter Roos

© Jewish Museum Berlin

“The situation is extremely serious; His Majesty the Emperor declared this afternoon that Germany is now at war.” Exactly one hundred years ago today, eighteen-year-old Leo Roos penned these lines to his parents and siblings back home in the West Palatine village of Brücken. But they were never to receive his letter, as the note on the envelope attests: Dispatch prohibited on account of the state of war. Return to sender.

Roos felt he was witnessing fateful times. He lived in Frankfurt, where he was apprenticed to a bank. He thought himself a city boy, much closer to momentous global events than his family was, off in its isolated village. He described the tense mood: → continue reading