With Her Art Shira Wachsmann Addresses the Nearly Forgotten Genocide of the Herero and Nama Peoples in Present-Day Namibia

The artist Shira Wachsmann in her workshop

CC-BY Saro Gorgis

The streets of Kreuzberg are soaked through with rain on this grey February day. Shira Wachsmann, a graceful young woman with short black hair, leads me into her atelier in a pre-war apartment. She doesn’t have much time. Her solo exhibition “Tribe Fire” is scheduled to open on 13 March 2016 in the gallery cubus-m in Berlin’s Schöneberg neighborhood (further information on the gallery’s website). It will remain there until 23 April. Large drawings, soon to become part of the Tribe Fire installation, hang in the atelier. “There’s still a lot to do,” the Israeli native explains.

Her most recent art project is spread across her desk: two postcards that Wachsmann designed for the Jewish Museum Berlin. She produced editions of 400 of each piece, which have been available for individual purchase since 1 April 2016 in the art vending machine of the museum’s permanent exhibition (more information on the art vending machine on our website). Wachsmann takes a seat in a green armchair and ponders the cards. They show two circular motifs, a form that appears throughout the artist’s work like a guiding principle. Here they depict an abstract diamond and a black sun. → continue reading

A Guest Entry by Rudij Bergmann

Accompanying our current exhibition, “No Compromises! The Art of Boris Lurie,” Rudij Bergmann’s film about the artist will premiere on 21 March 2016 (additional information available on our event calendar). In this guest entry, the filmmaker tells us how this very personal documentary came about.

The artist’s longing for Europe was palpable from the moment I first saw him in the dim light of an apartment hallway on New York’s 66th Street. Stepping into his home studio, confronted by this breathtaking collage of memory, it was immediately clear to me that Boris Lurie hadn’t fully left the concentration camps he survived with his father – at least mentally.

It was October 1996. A film for the television magazine BERGMANNsART, which I’m for all intents and purposes responsible for, was the reason to rush to see Lurie in New York. (The film, in German and with age restriction, is available on YouTube.)

It was the beginning of a long friendship. → continue reading

Program Director Cilly Kugelmann on the Exhibition “NO COMPROMISES! The Art of Boris Lurie”

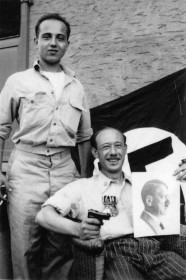

“As this image of Lurie with his brother-in-law Dino Russi from 1946 shows, the NO!art artists, in reclaiming the swastika symbol, robbed it of its symbolic value.” (Cilly Kugelmann)

Boris Lurie Art Foundation, New York

Our major retrospective dedicated to Boris Lurie opens 26 February 2016 (for more information see www.jmberlin.de/lurie/en). Blog editor Mirjam Bitter spoke with Cilly Kugelmann about the artist, his provocative work, and the possible impact today of the taboos that he broke throughout his career.

Mirjam Bitter: What is your view of Boris Lurie? What sort of a guy was he? What distinguished him as an artist?

Cilly Kugelmann: The man and the artist Boris Lurie was shaped by his experience of persecution and concentration camps under the Nazi regime. And yet, unlike other artists who faced similar experiences, I feel he cannot be described as a “Holocaust artist.” With the exception of some early drawings from 1946 and a few paintings from the late 1940s, he neither chronicled these events nor sought to interpret the Holocaust artistically in his work.

Then what role did the Holocaust play in Lurie’s work? → continue reading