When you do a search of our library catalog for Goethe you could get this idea: 70 hits for works by or about the German poet (by contrast, Schiller only gets 16). And until a few years ago the impressive 1867 Cotta’schen edition of Goethe appeared in our permanent exhibition. Many people used to ask the visitor’s desk: “Was Goethe Jewish?” No, he wasn’t. But for many Jews he was the paragon of German culture, and his works symbolized membership in the German educated middle-class.

Former Goethe installation in the permanent exhibition

© Jewish Museum Berlin, photo: Marion Roßner

A few months ago, the Richard M. Meyer Foundation gave us more than 100 books by and about Richard M. Meyer himself. The son of a banker, art collector, and man of letters was a Goethe scholar. Meyer never acquired a proper professorship, but his 1895 biography of Goethe won awards and was published again and again – as a single volume, in multiple volumes, as a people’s edition and a reserved edition. According to the biography, Goethe saw “nationalities merely as transitional forms” (Volksausgabe [People’s Edition] 1913, p. 352). Statements like this illustrate the dilemma of German-Jewish assimilation during that period. If a Jewish reader of Goethe placed the poet’s cosmopolitanism in the foreground, he exposed himself to the accusation of misunderstanding the German essence of his writings. But when he explicitly recognized just this quality in Goethe’s language, his very right to have a say was contested. → continue reading

On our “Open Day at the Academy,” this Sunday, 27 October 2013, we will celebrate the namesakes of the new public square in front of the Academy on Lindenstrasse: Fromet Mendelssohn, née Gugenheim, and her husband Moses Mendelssohn are now immortalized on Berlin’s cityscape, following much debate and deliberation. Reason enough to find out more about this exceptional couple!

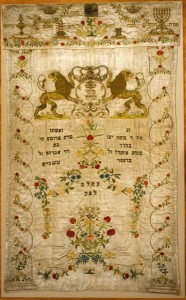

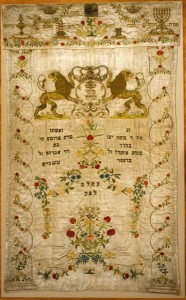

Inspired by deep religious feeling, Fromet and Moses Mendelssohn had Fromet’s wedding dress converted into a Torah curtain. They presented it to Berlin’s Jewish community, where, in the synagogue, it decorated the shrine.

You can find this and other objects relating to Moses Mendelssohn held by the Jewish Museum Berlin in our collections …

In the spring of 1761, when philosopher Moses Mendelssohn met the merchant’s daughter Fromet Gugenheim during a visit to Hamburg, his fate was sealed: he declared his love for her in a garden pavilion, and “stole a few kisses from her lips.” He returned, besotted, to Berlin and wrote to his friend Gotthold Ephraim Lessing:

“I have committed the folly of falling in love in my thirtieth year. The woman I wish to marry has no assets, is neither beautiful nor erudite; yet I am a lovesick beau, so smitten that I believe I could live with her happily ever after.”

The two were wed in June 1762. That they married for love was highly unusual: most marriages at the time were arranged by matchmakers. “[O]ur correspondence can do without ceremony,” Moses assured Fromet on 15 May 1761, in the very first of his letters to his bride: “…our hearts will respond.”

“Before I met you, my love, solitude was my Garden of Eden. But it is intolerable to me now.” Berlin, 24 October 1761 → continue reading

– a Youth Spent in Iran and Vienna

This week, from 21 to 27 October 2013, the Academy of the Jewish Museum Berlin, in cooperation with Kulturkind e.V., will host readings, workshops, and an open day for the public with the theme “Multifaceted: a book week on diversity in children’s and youth literature.” Employees of various departments have been vigorously reading, discussing, and preparing a selection of books for the occasion. Some of these books have already been introduced here over the course of the last months.

In her autobiographical graphic novel Persepolis, the author Marjane Satrapi, born in 1969, portrays the history of her native Iran as well as that of her own family. The two are closely interwoven. Marjane grew up in Iran during a time of upheaval: when she was ten, the Shah was overthrown and people danced in the streets. But the feeling of liberation was brief. Soon the new religious regime began to enforce its ideas of morality and decency. It forbade alcohol and Western music, insisted that even non-religious women wear the veil, and put opponents into prison or had them assassinated. Marjane’s open-minded, liberal parents are understanding and give her space and freedom. But she finds it difficult to adjust to the rules outside their home. She rebels against the dress codes, goes to parties, and argues with her teachers. → continue reading