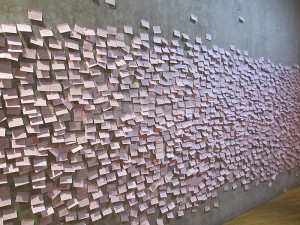

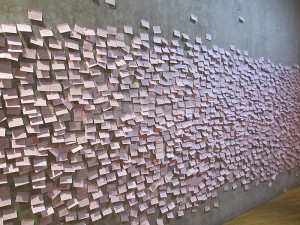

A wall full of questions at the exhibition “The whole truth” © Jewish Museum Berlin, photo: Thomas Valentin Harb

Just over a year ago the Jewish Museum’s special exhibition entitled “The whole truth… everything you always wanted to know about Jews” ended. The only remnants – aside from the animated discussions and empty display cases – were thousands of pink post-it notes, which we kept and read through painstakingly. In the upcoming months we want to respond to some of the questions, comments, and impressions that visitors left behind. Thus to the question above.

Orthodox women do not show their hair in public after their wedding. → continue reading

In Germany, you cannot rely on the weather being consistently sunny, even in the summertime. In the fall at the latest – dare we think of it already? – we will need to shake open our umbrellas again. Axel Stähler (comparative literature, University of Kent), has shown that the umbrella was once considered a Jewish attribute. He recently offered to share with Blogerim his research on the umbrella’s discursive significance in Wilhelminian Germany.

Dr. Stähler, how did you spot the “Jewish umbrella”?

Mbwapwa Jumbo from “Briefe aus Neu-Neuland”, Schlemiel 1.1 (November 1903), p. 2

I was first struck by an umbrella in the hands of the “Big Chief of Uganda,” Mbwapwa Jumbo, a fictitious reporter in the Jewish satirical magazine Schlemiel, who acted as a correspondent from a new Jewish colony in Africa. In fact, in 1903, the British government had proposed to Theodor Herzl to commit land to Jewish settlers in the British Protectorate of East Africa. This proposal, which came to be known as the Uganda Plan, was vehemently disputed in the Zionist movement, and rejected in 1905. No concerted colonial Jewish settlement of Uganda ever took place, although individual Jewish immigrants had built homes there earlier.

In nine letters published over the course of the magazine’s brief lifespan, from 1903 to 1907, the chatty and naïvely amicable Mbwapwa tells of the first Jewish colonists – Orthodox Mizrachi – and of what became of them: in funny prose spotted with Anglicisms, and increasingly also Yiddishisms, he describes how he and his countrymen converted to Judaism. He relates the murder of a reformist rabbi who had been smuggled into the country, and the reformers’ ensuing punitive military expedition. He reports on the colony’s political and cultural trials and tribulations, and, finally, on the emergence of the Zionist movement—since Uganda was not, after all, the Promised Land. → continue reading

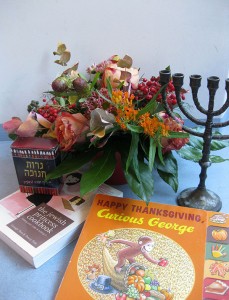

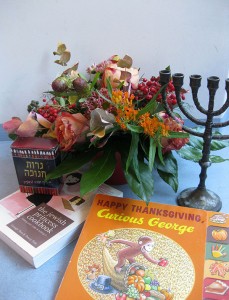

Menurkeys for Thanksgivukkah?

Research under way in preparation for Thanksgivukkah

Photo: Signe Rossbach

Chanksgiving! As a family of German-American Jewish-Protestant-Catholic-Puritan backgrounds, we do like to celebrate as many holidays as we can possibly fit into our family schedule – with Halloween, our twins’ birthday and the classic German lantern parade for St. Martin’s day making for an action packed twelve days at the beginning of November.

After a bit of a breather we’re heading into the next holiday season – with a bit of a twist this year. Usually Hanukkah – the Jewish festival of lights and miracles – is associated with the Christian festival of lights and a miraculous birth: Christmas. And that makes sense, sort of, superficially at least. A few years ago we had an entire exhibition titled “Chrismukkah” – a cultural history of the evolution of the two holidays, and this year on December 3, Rabbi Daniel Katz will present a truly enjoyable talk on how they really don’t fit together at all.

But Thanksgiving? → continue reading