The wedding barn decorated with lights and flowers

© Chuck Fishman

With young adults spending an increasing number of years out of wedlock, preparation for marriage is ever more elaborate: Bachelor and bachelorette parties in North America are notorious for distracting brides- and grooms-to-be with alcohol and promiscuity. Celebrations of a similar nature are called stag and hen nights in England. In traditional German circles, friends and relatives of wedding couples smash dishes on so-called Polterabend (English: rowdy evening). In modern ones, the couple and their friends careen through city streets with flashy paraphernalia, printed t-shirts, and plastic trumpets.

Currently, a group of young Jews in the US are adapting an eastern European pre-marriage tradition, called tisch (Yiddish: table, short for chosson’s tisch, or groom’s table). → continue reading

On 18 October, our next special exhibition “A Time for Everything: Rituals Against Forgetting” will open to the public. The exhibition met with great success at its previous venue in Munich. We therefore invited Bernhard Purin, director of the Jewish Museum Munich, to write a piece for our blog. He introduces us to an exhibit that is of relevance to this week’s holiday.

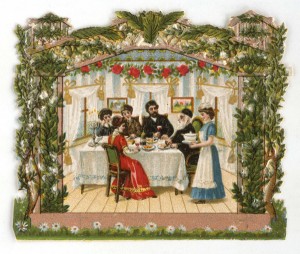

The Feast of Booths (“Sukkot” in Hebrew, from the word “sukkah,” meaning “tabernacle”) will be celebrated this year from 19–25 September. Along with Passover (Pesah) and Pentecost (Shavuot), it numbers among the three pilgrimage festivals, and commemorates the forty years Israelites spent wandering in the desert after the exodus from Egypt. The Third Book of Moses (23: 42–43) ordains:

“Ye shall dwell in booths seven days; all that are home-born in Israel shall dwell in booths; that your generations may know that I made the children of Israel to dwell in booths, when I brought them out of the land of Egypt: I am HaShem your G-d.”

Booths have been built ever since and their roofs covered with foliage, in keeping with this commandment. Rural Jews in Germany often erected such booths in the attic of their homes, and this tradition has been taken up at the Jewish Museum Franken in Fürth as well as at its Schwabach branch. Yet mobile booths which could be set up in the garden before the festival, then taken apart and packed away for the rest of the year, were also common. One booth of this kind survived in the village of Baisingen near Rottenburg am Neckar, where a large Jewish community once lived. → continue reading

Employees of the Jewish Museum Berlin respond:

“I like Rosh ha-Shanah, and new year festivities in general. I celebrate them all: birthdays, the High Holidays, and December 31st.” Naomi Lubrich, Media

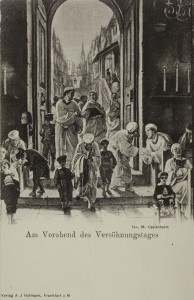

The postcard is the only copy of a painting by Moritz Daniel Oppenheim from 1873, which was destroyed in London in 1939. © Jewish Museum Berlin, photo: Jens Ziehe

You will find more postcards from the past in our Online Showcase

“I usually use the time between Rosh ha-Shanah and Yom Kippur to figure out what’s not going so well in my life and what I want to change. I take some time to think about it and take stock.” Sarah Hiron, Education

“The High Holidays, like the Sabbath, are a chance to make time for my spiritual faith. For me they are special – holy – days. They encourage me to carry on traditions and become more aware. At the same though, they mean time off, and that means nightlife, having fun, and sleeping in.” Roland Schmidt, Host

“Although I live a secular life the rest of the year and don’t go to synagogue, Yom Kippur has a great spiritual significance for me. I fast, turn off music and disregard other forms of entertainment. Instead the day is defined by humility, contemplation, silence, and reflecting on nature. Since it’s not a joyful celebration with one central ritual, Yom Kippur is different every year, so I connect it with new and ever-changing personal experiences.” Roman Labunski, Education