or What We Can Learn from Loving Women

Not long ago, we happened upon the website of a group of three young Jewish women “who care about different aspects of Jewish and Israeli identity and culture and who want to experience a meaningful Jewish life in Berlin.” They call themselves Hamakom (Hebrew: ‘the place’) and support, among others, more frequent encounters between Israelis and Jewish Germans. The group’s first event is a Tikkun lel Shavuot on the topic of “Women & Love,” the title clearly stating the theme of the evening. The event follows the tradition of studying and discussing specific Biblical texts and their interpretations on the night before Shavuot. This choice of topic reveals the meaning the holiday has in the discursive process of self-reflection.

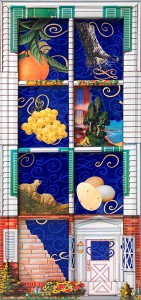

Jakob Steinhardt, Illustration to the Book of Ruth, 1955-1959, woodcut

© Jewish Museum Berlin, donation of Josefa Bar-On Steinhardt, Nahariya, Israel

Shavuot begins this year on the eve of 14 May and ends two days later. It is a holiday of unusually multifaceted significance, and it is rediscovered and redefined by every generation anew. Originally, the holiday celebrated the beginning of the harvest season, which included a pilgrimage to the Jerusalem Temple. Pilgrims brought their first fruit and two loaves of wheat-bread to the temple. In the Talmud, Shavuot is conceived of as the festival on which the population of Israel received the Torah. In preparation of this donation, the holiday is also described as an Atzeret, a joyous assembly, which involves a night of communal thinking and debating. Tikkun lel Shavuot, as this nightly symposium is called in Hebrew, means literally: ‘The betterment during the night of the Feast of Weeks.’ It was first mentioned in the kabbalistic Zohar-book and gained importance in the 16th century.

The Jewish understanding of collective studying and discussing differs from that of the Greeks; → continue reading

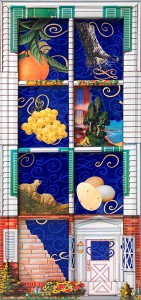

Seder Plate by Harriete Estel Berman, U.S.A., 2003 © photo: Jens Ziehe, Jewish Museum Berlin

Passover is not only a feast day evoking an historic event through a ritualized form of remembrance. It also appeals to reenact the exodus out of Egypt and envision divine mercy, freeing us from bondage and disenfranchisement. Like many Jewish holidays the original biblical Passover story has been and still is seen in relation to other historical events. The Egypt of the Exodus story turned into Ukraine and Belarus in the 17th century, when the Cossack chief Bogdan Chmielnicki allowed many hundreds of thousands of Jews to be murdered over the course of his struggle to liberate Poland. In the 20th century, Germany under the Nazi regime became the country to flee.

Through its culinarily-underscored recitation and discussion of the narrative, the seder provides a framework for each new re-interpretation. This appears primarily at the dinner: even while the symbolic dishes are determined by the Passover Haggadah, the other foods vary according to geography and the cultural conventions of the place where the celebration is taking place. There are especially numerous recipes for the “mortar,” the charoset, which resembles in color and texture the cementing agent used to build houses.

→ continue reading

In our permanent exhibition, there is a spot reserved for topics that are au courant: three prominently placed pot-bellied display windows that we call the “raviolis”.

“Ravioli” display windows in the permament exhibition © Jewish Museum Berlin, photo: Christiane Bauer

These display windows were filled once again with new exhibits for Purim, now. The new presentation looks at the festival from a feminist perspective and directs viewers’ attention to the latest developments substantially being shaped by Jewish women in the USA.

The focus of the presentation is on the two female characters of the Purim story that is read aloud at synagogue during the service: Esther and Vashti. Little attention has been paid to the latter for a long time. She was the first wife of the Persian King Ahasuerus, who cast her out because of her disobedience. He subsequently took the beautiful Jew Esther as a wife, who was shy and quiet, quite unlike the defiant Vashti. But over time Esther emerged from her reticence to transform into the courageous heroine we know, thwarting the conspiracy to murder the Persian Jews.

→ continue reading