The Festival of Liberation at the Front

Yesterday evening, Monday, 14 April 2014, was the start of the eight-day Passover festivities. These kick off each year with the first Seder, the name of which derives from the Hebrew word seder, meaning order, because a particular ritual sequence is observed the entire evening.

The ritual Seder program is laid down in the Haggadah, an often beautifully illustrated book. (Incidentally, some especially precious Haggadot are currently on display in our special exhibition “The Creation of the World” and our director of archives recently described in his blog why even a nondescript Haggadah might be of great value to a museum.) Traditional texts and songs are recited from the Haggadah. Symbolic dishes and drinks deck the tables, ready to be consumed at specific moments during the evening.

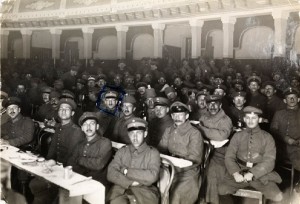

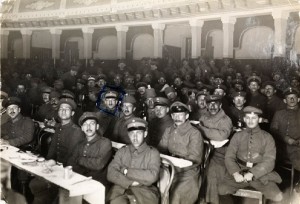

German soldiers celebrate Passover in the occupied town of Jelgava (near Riga). © Jewish Museum Berlin, photo: anonymous. Donated by Lore Emanuel

But why is this night different from all other nights? This is a question that Jews all over the world ask themselves year after year at the Seder dinner. The answer is: it is the festival of liberation, for it commemorates the Israelites’ exodus from slavery in ancient Egypt. Everyone is supposed to feel, each year, as if she or he personally is about to leave Egypt. As a token of tribute to this new-won freedom, people comfortably recline while eating and drinking—for to take this position was the prerogative solely of free individuals in antiquity, not of slaves. → continue reading

A Newly Acquired Passover Haggadah and Its Previous Owners in Kreuzberg

Next week, the first Passover Seder will be celebrated on the evening of April 14. All over the world Jews will gather with their family and friends around festively decked tables and partake in the centuries-old tradition of reciting the Haggadah. Its text describes the story of the Israelites’ liberation from slavery in Ancient Egypt and sets forth the order of the evening.

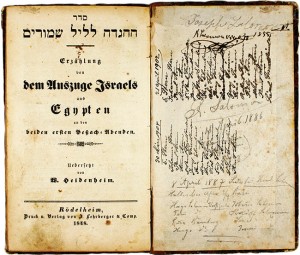

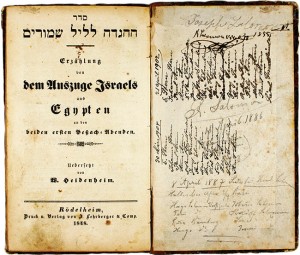

“An Account of Israel’s Exodus from Egypt on the First Two Evenings of Passover,” published in Rödelheim near Frankfurt, 1848

© Jewish Museum Berlin, photo: Aubrey Pomerance

A Haggadah in an online auction recently caught my eye, and I managed to purchase it for a negligible sum for the Jewish Museum Berlin. Published in 1848 in Roedelheim near Frankfurt under the title Erzählung von dem Auszuge Israels aus Egypten an den beiden ersten Pesach-Abenden (An Account of Israel’s Exodus from Egypt on the First Two Evenings of Passover), the book contains the Hebrew version of the Haggadah text, along with its translation into German by Wolf Heidenheim. It is the twentieth edition of the Roedelheimer Haggadah that first appeared in 1822/23, there with the German translation in Hebrew characters. In 1839, the translation first appeared in Roman letters, as is the case with our new acquisition.

There is, to be sure, nothing remarkable about this edition from 1848. → continue reading

An Interview with Cilly Kugelmann about the Exhibition “The Creation of the World: Illustrated Manuscripts from the Braginsky Collection”

Mirjam Wenzel: At the forthcoming exhibition, the Jewish Museum Berlin will present its first ever show of outstanding examples of the centuries-old Jewish scriptural tradition. What significance does scripture—the written word—have in the Jewish tradition?

Cilly Kugelmann and Mirjam Wenzel

© Jewish Museum Berlin, photo: Katrin Möller

Cilly Kugelmann: In early collections of rabbinic interpretations of biblical texts—the so-called midrashim—it is written that the Torah existed before the world was created. Some rabbis see the Torah quasi as a manual of creation that God drew on during his seven-day feat. Such interpretations demonstrate the extraordinary significance attributed to scripture in Judaism.

Following the loss of the geographic homeland Israel, sacrifices and pilgrimages to specific temples were abandoned in favor of prayer services that could take place anywhere—and the traditional texts themselves consequently became the most important, pivotal moment of the rite. To this day, the study and interpretation of biblical writings is the primary focus of Jewish intellectual life.

Why is René Braginsky’s Collection of illuminated manuscripts being presented under the title “The Creation of the World?” → continue reading