Why a particular subject captures the interest of the public at a given time is not always immediately apparent. Conversion, for instance, has become the topic of conferences, lectures and exhibits in German-speaking Europe without any notable change in its social significance nor religious practice.

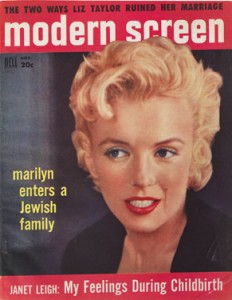

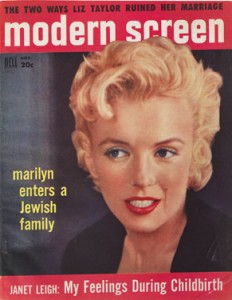

Picture in the current special exhibition “The Whole Truth” accompanying the question: Jew or non-Jew? Marilyn Monroe on the cover of the Modern Screen Magazine, November 1956

© Jewish Museum Berlin, photo: Jens Ziehe

The number of converts to Judaism is invariably small. According to the data collected by the Zentralwohlfahrtsstelle der Juden in Deutschland, on average 64 conversions are carried out yearly in the various German-Jewish communities, and since the year 2000, the number has remained fairly stable. Nor has the size of the Jewish communities varied much. For over a decade, the number of members has stabilized at around 105.000. In relation to the size of the community, the total number of converts since 1990, 1.366, makes up under one percent of the Jewish community. The number of Jews leaving the communities is slightly higher, around one hundred a year, yet the number is not particularly meaningful, because it includes people who leave for all sorts of reasons, including financial. By all accounts, today’s Jewish converts are a minute and exotic minority.

Yet the topic is currently being discussed with much enthusiasm. → continue reading

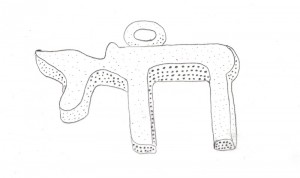

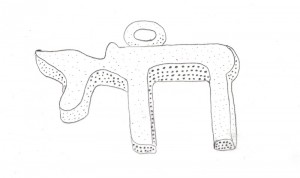

The Involuntary Moose

Last summer, a snigger went viral in the Jewish online community when an eBay entrepreneur posted a pendant of a Navajo moose. Labeled a “Unique Vintage Navajo Moose 925 Sterling Silver Pendant, marking 0.8 grams,” the trinket for sale was in fact a Jewish amulet depicting the Hebrew word “chai” for “life/living.” The motif is popular in Jewish jewelry. It consists of the two letters chet and yod and is not commonly mistaken for an animal. But this particular example simplified the letters and joined them together, which made them appear, quite truly, like an antlered moose in Native American style. → continue reading

or What We Can Learn from Loving Women

Not long ago, we happened upon the website of a group of three young Jewish women “who care about different aspects of Jewish and Israeli identity and culture and who want to experience a meaningful Jewish life in Berlin.” They call themselves Hamakom (Hebrew: ‘the place’) and support, among others, more frequent encounters between Israelis and Jewish Germans. The group’s first event is a Tikkun lel Shavuot on the topic of “Women & Love,” the title clearly stating the theme of the evening. The event follows the tradition of studying and discussing specific Biblical texts and their interpretations on the night before Shavuot. This choice of topic reveals the meaning the holiday has in the discursive process of self-reflection.

Jakob Steinhardt, Illustration to the Book of Ruth, 1955-1959, woodcut

© Jewish Museum Berlin, donation of Josefa Bar-On Steinhardt, Nahariya, Israel

Shavuot begins this year on the eve of 14 May and ends two days later. It is a holiday of unusually multifaceted significance, and it is rediscovered and redefined by every generation anew. Originally, the holiday celebrated the beginning of the harvest season, which included a pilgrimage to the Jerusalem Temple. Pilgrims brought their first fruit and two loaves of wheat-bread to the temple. In the Talmud, Shavuot is conceived of as the festival on which the population of Israel received the Torah. In preparation of this donation, the holiday is also described as an Atzeret, a joyous assembly, which involves a night of communal thinking and debating. Tikkun lel Shavuot, as this nightly symposium is called in Hebrew, means literally: ‘The betterment during the night of the Feast of Weeks.’ It was first mentioned in the kabbalistic Zohar-book and gained importance in the 16th century.

The Jewish understanding of collective studying and discussing differs from that of the Greeks; → continue reading