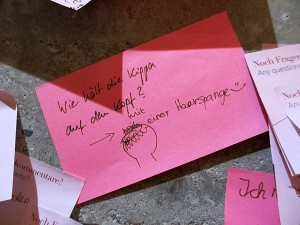

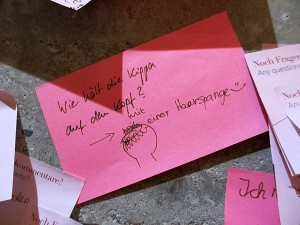

“How does a kippah stay on?”

Our current special exhibition “The Whole Truth… everything you always wanted to know about Jews” is based on 30 questions posed to the Jewish Museum Berlin or its staff over the past few years. In the exhibition, visitors have their own opportunity to ask questions or to leave comments on post-it notes. Some of these questions will be answered here in our blog. This month’s question is: “How does a kippah stay on?”

“How does a kippah stay on?”

© photo: Anina Falasca, Jewish Museum Berlin

If a non-Jew tries on a kippah, it usually falls off. This isn’t fair, but let’s examine the circumstances more closely. When tourists visit the Jewish cemetery in Prague, all men are asked to wear a kippah. Those who travel kippah-free are requested to don a blue, sharply-creased, circular piece of paper. The precarious kippah is inevitably subjected to the winds off the Vltava and flutters away. Comparably, a non-Jewish man attending a synagogue ceremony such as a marriage or Bar Mitzvah, will usually be requested to wear a kippah. Here, a stiff yet slippery synthetic satin kippah is ubiquitous. No guest stands a chance.

What then is the secret to making a kippah stay on? → continue reading

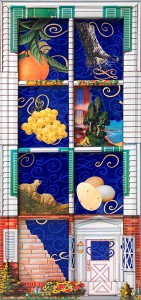

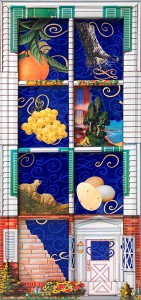

Seder Plate by Harriete Estel Berman, U.S.A., 2003 © photo: Jens Ziehe, Jewish Museum Berlin

Passover is not only a feast day evoking an historic event through a ritualized form of remembrance. It also appeals to reenact the exodus out of Egypt and envision divine mercy, freeing us from bondage and disenfranchisement. Like many Jewish holidays the original biblical Passover story has been and still is seen in relation to other historical events. The Egypt of the Exodus story turned into Ukraine and Belarus in the 17th century, when the Cossack chief Bogdan Chmielnicki allowed many hundreds of thousands of Jews to be murdered over the course of his struggle to liberate Poland. In the 20th century, Germany under the Nazi regime became the country to flee.

Through its culinarily-underscored recitation and discussion of the narrative, the seder provides a framework for each new re-interpretation. This appears primarily at the dinner: even while the symbolic dishes are determined by the Passover Haggadah, the other foods vary according to geography and the cultural conventions of the place where the celebration is taking place. There are especially numerous recipes for the “mortar,” the charoset, which resembles in color and texture the cementing agent used to build houses.

→ continue reading

Are we allowed to drive a car to synagogue services on Shabbat? If my father is Jewish and my mother is Christian, what am I? Can an uncircumcised man be Jewish?

Seven rabbis (left to right): Joshua Spinner, Irith Shillor, Daniel Katz, Julien-Chaim Soussan, Jonah Sievers, Avichai Apel, Gábor Lengyl

© Jewish Museum Berlin, photos: Thomas Valentin Harb

The new special exhibition, “The Whole Truth… everything you always wanted to know about Jews,” deals with common as well as uncommon questions about Judaism. We put some of these questions to seven rabbis and filmed their responses. All of them serve in Germany and represent a wide spectrum of religious belief: orthodox, liberal, conservative, progressive.

Inspired by research done on a number of Internet forums with names like “Ask the Rabbi,” “Askmoses,” and “Dear Rabbi,” in which rabbis from all over the world answer questions on how to handle religious law in everyday life, we organized the shooting of this film → continue reading