The Jewish Museum is located in the well-known Berlin neighborhood of Kreuzberg, which is also home to a 66-meter high hill that gave the district its name in 1920: Kreuz meaning ‘cross’ and Berg ‘mount’ or ‘hill’. A monument designed by Friedrich Schinkel had been erected there about 100 years prior in memory of the war of liberation from Napoleon. On top it has always been bedecked with an Iron Cross. Prussian King Friedrich Wilhelm III first endowed the building of the monument 200 years ago, on 10 March 1813, the birthday of his late Queen Luise. A drawing of Schinkel’s design for the Iron Cross has been passed down to the Kupferstichkabinett’s collection (Museum of Prints and Drawings). In 1870 and 1914 respectively, Emperors Wilhelm I and II made subsequent endowments of the Iron Cross for particular service by German soldiers.

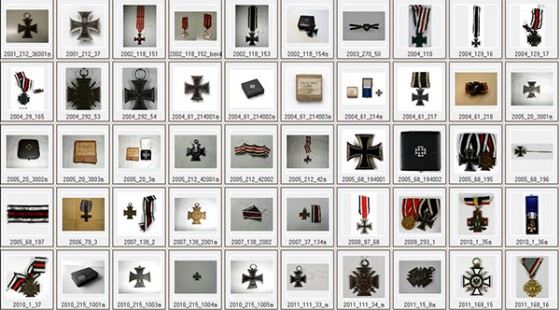

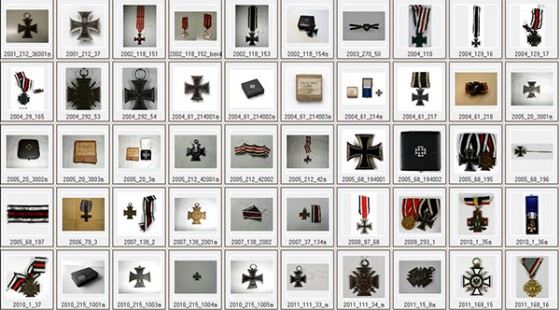

Numerous Iron Crosses can be found in the Jewish Museum’s collection, in many cases together with the respective certificates.

Iron Crosses in Kreuzberg – view of the object data bank of the Jewish Museum

© Jewish Museum Berlin

They nearly all date from the time of the First World War, in which around 100,000 Jewish soldiers participated on the German side. Among them were Julius Fliess (1876-1955) and Max Haller (1892-1960), whose medals are now in the Jewish Museum’s possession. → continue reading

My Two Hours as a Living Exhibition Object in the Show “The Whole Truth“

This was a truly extraordinary experience. The best moments were when the visitors started talking not just to me but to each other, and we wound up talking about Wagner and the weather rather than ‘just’ about growing up Jewish – or, more specifically, in my case as the daughter of a Jewish-American mother and a German, (formerly) Protestant father – in Germany and how odd it was to be sitting in a glass showcase in an exhibition.

Signe Rossbach in the exhibition “The Whole Truth”, April 8, 2013

© Jewish Museum Berlin, photo: Michal Friedlander

I was reminded of the moment in 1998 when I returned to Germany from the U.S. (although I did not want to see it that way at the time). The German publisher I was working for in New York had just been appointed State Minister of Culture by Gerhard Schröder, and I continued working for him in the Federal Chancellery, first in Bonn, then in Berlin. Back in New York, an editor at Henry Holt said to me: “Well, well, isn’t that a great job for a good little Jewish girl, working in the German government?” I thought about it, and said: “Exactly.”

So, I guess this was what brought me to sit in a glass showcase in a show at the Jewish Museum Berlin, where I have been working for twelve years now, on a seemingly quiet Monday afternoon. In my two hours of being a living exhibition object, I … → continue reading

In the past, a number of literary texts on Jewish topics contributed to Jewish culture in various ways. Some documented and revitalized oral history and folk tales in an attempt to save them from oblivion (e.g. Martin Buber’s Tale of the Hasidim); others made Jewish topics palatable to the majority society (e.g. Sidney Taylor’s All-of-a-Kind Family); and still others helped to build a Jewish community around shared experiences of ritual, emigration and persecution (e.g. Friedrich Torberg’s Tante Jolesch or The Decline of the West in Anecdotes).

In the past, a number of literary texts on Jewish topics contributed to Jewish culture in various ways. Some documented and revitalized oral history and folk tales in an attempt to save them from oblivion (e.g. Martin Buber’s Tale of the Hasidim); others made Jewish topics palatable to the majority society (e.g. Sidney Taylor’s All-of-a-Kind Family); and still others helped to build a Jewish community around shared experiences of ritual, emigration and persecution (e.g. Friedrich Torberg’s Tante Jolesch or The Decline of the West in Anecdotes).

Nathan Englander, one of the most sophisticated and provocative current writers, shares none of these intentions. His latest book, What We Talk About When We Talk About Anne Frank, is a collection of eight short stories loosely bound together under the title of (and a quote from) the first story, arising from a heated conversation about genocide; it refers to Anne Frank not as a historical figure, but as a metonym of victimhood. Accordingly, the stories reflect on the effect of Jewish themes, such as religion, the Holocaust and Israel, on modern Jewish identities. The author’s perspective is from within – he was born in 1970 to an Orthodox-Jewish family in New York – and critical. His gripping, intimate theatre-like episodes are fraught with tense dialog questioning the validity of Jewish cultural practice: → continue reading