The Tragic Fate of Shmuel Dancyger Z. L.

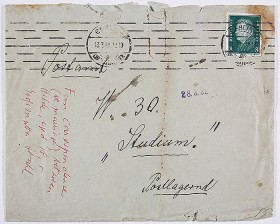

The family at the grave of Shmuel Dancyger; Jewish Museum Berlin, gift of Morris Dancyger

During a visit to my hometown of Calgary Alberta, Canada in the summer of 2014, I had the opportunity to meet with Morris and Ann Dancyger, both child survivors of the Holocaust. Morris Dancyger was one of the very few children to have been liberated by the Russians at Auschwitz on 27 January 1945. In the iconic footage of the children displaying their tattooed arms, four year old Morris is in the center of the picture. Ann Dancyger and her mother had miraculously survived an execution in 1942 near the town of Ratno where she was born, and spent nearly three years thereafter in hiding. After a nearly two year trek to Germany following the end of the war, she was able to come to Calgary where relatives lived. I had not known the Dancygers while growing up in the city, and although I had much later read about the tragic fate of Morris Dancyger’s father Shmuel, I was completely unaware that his wife and children had settled in Calgary. → continue reading

An Early April Fool’s Joke from the Year 1931

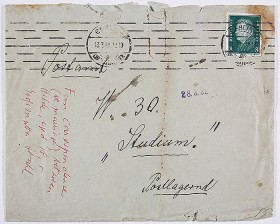

Envelope posted 13 March 1931; Jewish Museum Berlin, Gift of Margaret Littman and Susan Wolkowicz, the daughters of Hilde Gabriel née Salomonis

Sometimes figuring out how to classify a document correctly according to its historical context can depend on just one tiny, even seemingly unrelated detail. I was reminded of this again while working on the inventory of a recent donation to our archive. With more than 3,000 documents, photographs, and objects, the Gabriel-Salomonis family collection includes among other things an extensive correspondence. This consists of letters, postcards, and even telegrams, and as I sorted through these items, I came across an exchange of four letters from the early spring of 1931. Two were handwritten: composed and signed, quite legibly, by the then 72-year-old, Berlin resident Ernestine Stahl (1858–1933). The author of the other two type-written letters was at first uncertain, not least because his signature was missing. Ernestine Stahl addressed him in her replies only as “Sir” and “Dear Sir.”

I was able to solve this little riddle, however, by looking at an envelope that turned up elsewhere of the bundle of papers but appeared to belong to this brief exchange. → continue reading

A Guest Entry by Rudij Bergmann

Accompanying our current exhibition, “No Compromises! The Art of Boris Lurie,” Rudij Bergmann’s film about the artist will premiere on 21 March 2016 (additional information available on our event calendar). In this guest entry, the filmmaker tells us how this very personal documentary came about.

The artist’s longing for Europe was palpable from the moment I first saw him in the dim light of an apartment hallway on New York’s 66th Street. Stepping into his home studio, confronted by this breathtaking collage of memory, it was immediately clear to me that Boris Lurie hadn’t fully left the concentration camps he survived with his father – at least mentally.

It was October 1996. A film for the television magazine BERGMANNsART, which I’m for all intents and purposes responsible for, was the reason to rush to see Lurie in New York. (The film, in German and with age restriction, is available on YouTube.)

It was the beginning of a long friendship. → continue reading