An Interview with Lina Khesina

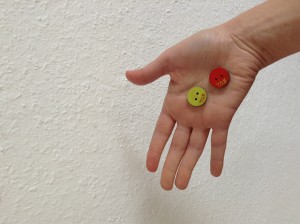

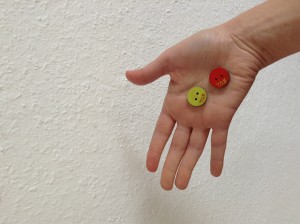

30 July 2014 is International Friendship Day. But how do we commemorate friendship? Or how do we make it visible? We consulted with communications designer Lina Khesina to find out. She devised a pair of ‘friendship buttons’ that you can get at the moment from the art vending machine in our permanent exhibition. One of them features the word “Tsemed” in Hebrew script, and the other one the word “Chemed.”

The buttons “Tsemed” and “Chemed”.

Photo courtesy of the artist

Lisa Albrecht: Lina, why did you develop this item in particular for the art vending machine?

I had the idea of showing the beauty of the Hebrew language and transmitting it in an everyday way. I don’t actually speak Hebrew myself, but purely from a musical perspective I find it and Spanish the two most beautiful languages. So I really wanted to discover Hebrew for myself and find a constellation of words in the language that I could play with. That’s how these buttons with the wordplay emerged.

How did the wordplay occur to you?

In Russian, best friends are often called “nje rasléj wodá”, which more or less means “even water cannot destroy this bond.” I did some research on whether there’s such an idiom in Hebrew as well and thus learned about “Tsemed Chemed.” Translated literally, it means “sweet entanglement” or “fine pair”, and is an expression for ‘close friends.’

What do these two words have to do with the buttons?

Buttons get sewed on with a thread and become then ‘entangled,’ or interwoven, with the material. Close friends experience something similar, even when they live thousands of kilometers apart. Like the buttons, they’re connected to each other by the thread and the adage. → continue reading

in Conversation with Emile Schrijver, Curator of the Braginsky Collection

What made you decide to be curator of a manuscript collection?

When I studied Hebrew in Amsterdam, a lecturer took us to see the University of Leiden’s collection of medieval manuscripts. In the impressive vaults, I saw ancient manuscripts for the first time: the only manuscript of the Jerusalem Talmud (Yerushalmi), for instance, and one of the earliest Rashi manuscripts. Seeing these ancient sources, and gaining first-hand experience of living history, was overwhelming. Historical books had a strong effect on me. I subsequently studied at the Bibliotheca Rosenthaliana, the Jewish library at the University of Amsterdam, where I later began to work. A few years ago, Mr. Braginsky was looking for a curator for his first exhibition in Europe. Mutual acquaintances from the international circle of manuscript specialists put us in touch with one another. We got along well and were soon able to establish a good, trusting working relationship

What do you do as a curator of the Braginsky Collection?

Emile Schrijver and the Harrison Miscellany © and photo: Darko Todorovic, Dornbirn (A)

I take care of the collection. I am responsible for Mr. Braginsky’s new acquisitions and for his existing objects. Most new acquisitions are delivered with a short description. Others we describe and photograph, before adding them to our inventory. I carefully examine the books’ condition and, if necessary, commission their restoration. I’m also responsible for monitoring the climate in the storerooms. Inquiries concerning exhibitions and reproductions are a lot of work for us. The process of digitizing our stock is ongoing. Occasionally, scholars wish to view specific works at length. We also organize presentations on our own premises, on behalf of the European Association of Jewish Museums, for example. Public relations for events such as the Jewish Book Week in London in 2013 likewise require a great deal of preparation.

What makes the Braginsky Collection so special? → continue reading

An Interview with René Braginsky

When did you start collecting and how large is your collection?

René Braginsky: I started collecting books more than twenty years ago. It was my son’s Bar Mitzvah, and I was looking for an illustrated blessing for the celebration. Since I could not find one, we made do with a copy. For his wedding, however, we were able to reproduce a blessing from our own collection. As I slowly acquired a taste for collecting, I bought more objects, and of increasingly quality, whenever possible. A good friend of mine, an older collector, encouraged me. The Judaica collection now comprises more than 700 pieces: books mainly, but also illustrated wedding contracts and Esther scrolls.

What motivates you to collect Hebrew manuscripts? Do you collect with a specific objective or mission in view?

Interior view of the special exhibition “The Creation of the World. Illustrated Manuscripts from the Braginsky Collection” © Jewish Museum Berlin, photo: Martin Adam

I’m interested, first and foremost, in the direct connection with Jewish history, with my view of Jewish history. I find the sheer variety of illustrations fascinating, as well as the regional and national influences they display. Jewish books in Germany are primarily German books, just as Jewish books from Spain are primarily Spanish and those from Morocco Moroccan. Jews lived in diverse regions, in a diaspora, and the illustrations in the books reflect this. And these old books so full of erudition bring me peace and make me confident, too, that whatever is really important will always survive. The mission, if there is such a thing, is my wish to share them freely, instead of hiding these treasures from the world. That is why we published websites (braginskycollection.com und braginskycollection.ch) , put two iPad apps online (Braginsky Collection und Braginsky Collection Berlin) and chose to exhibit a part of our collection in Berlin, for the fifth time. Over the years, the exhibitions and online sources have enabled tens of thousands of people all over the world—Jews and non-Jews —to share our enjoyment of the collection.

Do you believe the market for collectors of Judaica and Hebrew manuscripts has changed over the last few decades? Have you come across any counterfeiters or crooked dealers? → continue reading