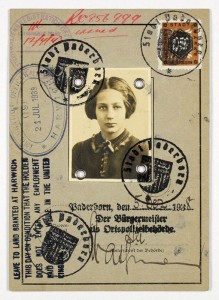

Beate Rose’s childhood passport

© Jewish Museum Berlin, donated by Beatrice Steinberg

75 years ago today, on 2 December 1938, the first of the Kindertransport rescue missions arrived in England. Beatrice Steinberg (née Beate Rose), a benefactor of the Jewish Museum Berlin, was among the last of the Jewish children to be saved in this way, by mass evacuation from Nazi-occupied territories. In her memoirs, which are held in our archives, she recalls her departure from Germany in the summer of 1939:

“My mother took me to the train, which turned out to be one of the last Kindertransporte to England […]. I was so excited that I rushed up the station steps without even saying goodbye to my mother. She called me back. We gave each other a hug and a kiss, then I boarded the train. I stood at the window and we waved goodbye. That was the last time I ever saw her.”

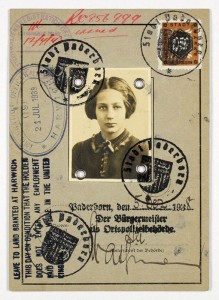

Beate Rose’s number tag from the “Kindertransport” rescue mission

© Jewish Museum Berlin, donated by Beatrice Steinberg

For Beatrice, only twelve years old at the time, the trip was an adventure; for her parents, the decision to let her go off alone, into the unknown, must have been made in great despair. The mass evacuation of children was launched three weeks after the November pogrom. Beate’s father was a prisoner in Buchenwald concentration camp at the time. Like hundreds of thousands of Jewish men and women, her parents hoped to leave Germany as soon as possible. But which country would open its borders to the mass of refugees? Visa restrictions and a bewildering amount of red tape made emigration a protracted and arduous undertaking. → continue reading

Menurkeys for Thanksgivukkah?

Research under way in preparation for Thanksgivukkah

Photo: Signe Rossbach

Chanksgiving! As a family of German-American Jewish-Protestant-Catholic-Puritan backgrounds, we do like to celebrate as many holidays as we can possibly fit into our family schedule – with Halloween, our twins’ birthday and the classic German lantern parade for St. Martin’s day making for an action packed twelve days at the beginning of November.

After a bit of a breather we’re heading into the next holiday season – with a bit of a twist this year. Usually Hanukkah – the Jewish festival of lights and miracles – is associated with the Christian festival of lights and a miraculous birth: Christmas. And that makes sense, sort of, superficially at least. A few years ago we had an entire exhibition titled “Chrismukkah” – a cultural history of the evolution of the two holidays, and this year on December 3, Rabbi Daniel Katz will present a truly enjoyable talk on how they really don’t fit together at all.

But Thanksgiving? → continue reading

Teddy bear that belonged to Ilse Jacobson (1920-2007), textile, straw, glass, ca. 1920 to 1930, in our online collection

56,250. This is the number that comes up when I search our collection’s database for its complete holdings. 56,250 data sets describing, for the most part, individual objects, and occasionally entire mixed lots. You can now see 6,300 of these objects online. Releasing this information to the public provokes mixed feelings on the part of museum staff: we have a lot to say about many of these objects. Many of them don’t speak for themselves. You can’t tell, for instance, that this teddy bear belonged to a child emigrating from Germany. The meaning of many documents and photographs lies likewise to a large extent in their biographical or political history. They require sufficient detail and well-chosen catchwords to help visitors find other objects related to the same topic.

With this project, we have to proceed pragmatically. 15-30 minutes of working time per object is a lot if you have to inventory a mixed lot with 250 units. We verify everything, including things that occur to us as we’re working. We are aware that there’s more to write about – and there would be more to correct, – if we had the time for more thorough research. Yet we can only make forays into the library or even into the archive for special projects or particularly important objects. And so we rely to a great extent on digital sources. → continue reading