Search Results for

"question"

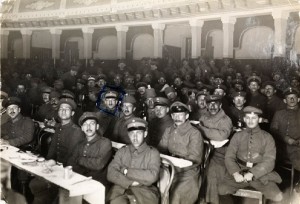

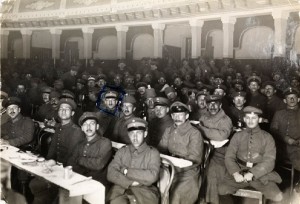

The Festival of Liberation at the Front

Yesterday evening, Monday, 14 April 2014, was the start of the eight-day Passover festivities. These kick off each year with the first Seder, the name of which derives from the Hebrew word seder, meaning order, because a particular ritual sequence is observed the entire evening.

The ritual Seder program is laid down in the Haggadah, an often beautifully illustrated book. (Incidentally, some especially precious Haggadot are currently on display in our special exhibition “The Creation of the World” and our director of archives recently described in his blog why even a nondescript Haggadah might be of great value to a museum.) Traditional texts and songs are recited from the Haggadah. Symbolic dishes and drinks deck the tables, ready to be consumed at specific moments during the evening.

German soldiers celebrate Passover in the occupied town of Jelgava (near Riga). © Jewish Museum Berlin, photo: anonymous. Donated by Lore Emanuel

But why is this night different from all other nights? This is a question that Jews all over the world ask themselves year after year at the Seder dinner. The answer is: it is the festival of liberation, for it commemorates the Israelites’ exodus from slavery in ancient Egypt. Everyone is supposed to feel, each year, as if she or he personally is about to leave Egypt. As a token of tribute to this new-won freedom, people comfortably recline while eating and drinking—for to take this position was the prerogative solely of free individuals in antiquity, not of slaves. (more…)

Dealing Creatively with Ethnic Classifications

Book cover

© Draupadi Verlag

Tomorrow at the Academy of the Jewish Museum Berlin, Urmila Goel and Nisa Punnamparambil-Wolf will introduce the book they edited, InderKinder – Über das Aufwachsen und Leben in Deutschland (Indian-Children: on Growing Up and Living in Germany, published by Drapaudi Verlag). It’s the third in a series of events on “New German Stories” where, with the aid of individual biographies, we examine Germany’s historical and current status as an immigration society. On this occasion we’ll focus on the children of immigrants from India, who gained public awareness for the first time during the “Green Card” campaign of 2000.

Prior to the reading and discussion tomorrow, we asked the two editors, Nisa Punnamparambil-Wolf and Urmila Goel, three questions:

What made you choose this title?

We’re referring with this title to the marginalizing “Kinder statt Inder” (children instead of Indians) campaign of the year 2000. The wordplay of InderKinder (Indian-children) is meant ironically: it was important to us to find a creative way to deal with these attributions. With the book, we want to show the varied ways that people who grew up and live in Germany handle the classification of being a child of Indian immigrants.

The book consists of two parts, autobiographical stories and essays. How would you explain your concept?

(more…)

On Why the Death of Stuart Hall Is a Loss for our Academy Programs

Stuart Hall, the renowned British cultural theorist and sociologist, passed away exactly one month ago, on 10 February 2014. His death prompted in us a deep sense of personal loss. His groundbreaking writings on cultural studies, in particular on racial inequality, were first translated into German in the mid 1990s—a time when people here were beginning to acknowledge the importance of racism as an issue.

Silent vigil of the Jewish Community at the Putlitz Bridge Deportation Memorial

Photo: Michael Kerstgens, Berlin Tiergarten, 1992

Hall’s approach incited a new discussion and coined a new vocabulary: until then, Germans in the Federal Republic had spoken of “Fremdenfeindlichkeit” (xenophobia), which they regarded as a marginal social phenomenon. Politicians and the media spoke matter-of-factly of society “reaching breaking point” when “the boat gets too full” owing to “Überfremdung.” The latter term denotes the state of ‘being overrun by foreigners.’ It is itself deeply racist and was accordingly voted Non-word of the Year 1993. “Being overrun” was presumed however to be explanation enough for the fire-bombings and other attacks then being carried out almost daily on asylum-seekers’ accommodation centers or immigrants’ apartments—and likewise for the hate campaigns, man-hunts, and pogrom-type riots erupting in Rostock, Hoyerswerda, and elsewhere, or the emergence of no-go areas in other towns and rural centers. In consequence, the law on asylum was altered in 1993 such that judicial opinion held it to have been “de facto repealed.” Therefore, anyone who wished to address the issue of racism as a structural phenomenon and thereby draw on theoretically sound academic sources had necessarily to turn to authors from England, France, the USA, or Canada—and repeatedly to Stuart Hall. (more…)