An Appeal for Recognition and Dignity

“We used to throw stones at her – we thought she was a witch.” With these words, a former resident of Rishon LeZion ruefully told me of her childhood encounters with the sculptor and doll maker, Edith Samuel. Edith wore her long, dark, European skirts under the searing Middle Eastern sun and suffered from a physical deformity. The daughter of a liberal German rabbi, Edith and her sister Eva were both artists who left their home city of Essen in the 1930s and immigrated to Palestine.

The pottery wheel belonging to Paula Ahronson, Eva Samuel’s business partner, is preserved in private hands and untouched since her death in 1998

© Jewish Museum Berlin, photo: Michal Friedlander

The Samuel sisters worked long hours, struggled to earn a living and did not gain the recognition that they deserved, during their lifetimes. The exhibition “Tonalities” at the Jewish Museum Berlin aims to bring forgotten women artists back into the public arena. It presents Eva Samuel’s works and that of other women ceramicists who were forced to leave Germany after 1933.

My search for transplanted German, Jewish women in the applied arts began many years prior to my encounter with the Samuel sisters. It was Emmy Roth who first captured my attention. Born in 1885, Roth was an exceptionally talented and internationally successful silversmith, who worked in Berlin. She immigrated to Palestine and fell into obscurity, ultimately taking her own life in 1942. Her male refugee colleagues, Ludwig Wolpert and David Gumbel, were appointed to teach metalwork at the Jerusalem New Bezalel School of Art in the late 1930s. They are feted in Israel today, whereas Roth is still completely unknown there. → continue reading

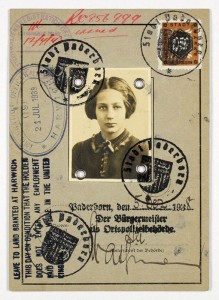

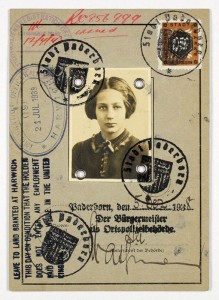

Beate Rose’s childhood passport

© Jewish Museum Berlin, donated by Beatrice Steinberg

75 years ago today, on 2 December 1938, the first of the Kindertransport rescue missions arrived in England. Beatrice Steinberg (née Beate Rose), a benefactor of the Jewish Museum Berlin, was among the last of the Jewish children to be saved in this way, by mass evacuation from Nazi-occupied territories. In her memoirs, which are held in our archives, she recalls her departure from Germany in the summer of 1939:

“My mother took me to the train, which turned out to be one of the last Kindertransporte to England […]. I was so excited that I rushed up the station steps without even saying goodbye to my mother. She called me back. We gave each other a hug and a kiss, then I boarded the train. I stood at the window and we waved goodbye. That was the last time I ever saw her.”

Beate Rose’s number tag from the “Kindertransport” rescue mission

© Jewish Museum Berlin, donated by Beatrice Steinberg

For Beatrice, only twelve years old at the time, the trip was an adventure; for her parents, the decision to let her go off alone, into the unknown, must have been made in great despair. The mass evacuation of children was launched three weeks after the November pogrom. Beate’s father was a prisoner in Buchenwald concentration camp at the time. Like hundreds of thousands of Jewish men and women, her parents hoped to leave Germany as soon as possible. But which country would open its borders to the mass of refugees? Visa restrictions and a bewildering amount of red tape made emigration a protracted and arduous undertaking. → continue reading

Teddy bear that belonged to Ilse Jacobson (1920-2007), textile, straw, glass, ca. 1920 to 1930, in our online collection

56,250. This is the number that comes up when I search our collection’s database for its complete holdings. 56,250 data sets describing, for the most part, individual objects, and occasionally entire mixed lots. You can now see 6,300 of these objects online. Releasing this information to the public provokes mixed feelings on the part of museum staff: we have a lot to say about many of these objects. Many of them don’t speak for themselves. You can’t tell, for instance, that this teddy bear belonged to a child emigrating from Germany. The meaning of many documents and photographs lies likewise to a large extent in their biographical or political history. They require sufficient detail and well-chosen catchwords to help visitors find other objects related to the same topic.

With this project, we have to proceed pragmatically. 15-30 minutes of working time per object is a lot if you have to inventory a mixed lot with 250 units. We verify everything, including things that occur to us as we’re working. We are aware that there’s more to write about – and there would be more to correct, – if we had the time for more thorough research. Yet we can only make forays into the library or even into the archive for special projects or particularly important objects. And so we rely to a great extent on digital sources. → continue reading