Golem Costume for Death, Destruction, and Detroit II at the Schaubühne Berlin, 1987. Directed by Robert Wilson; Lender: The Jewish Museum, New York

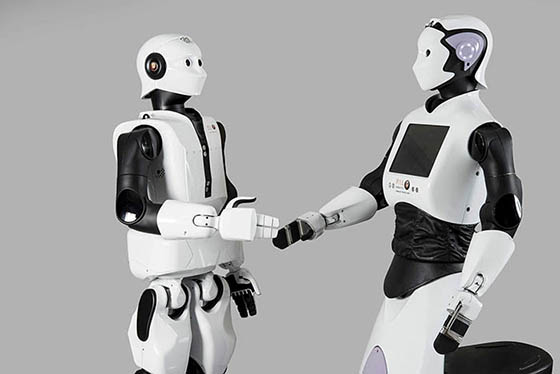

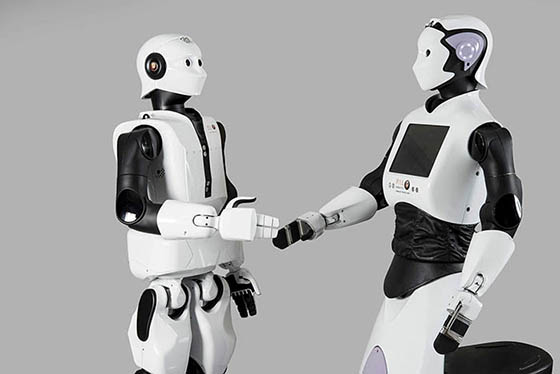

The Golem is brought to life from inanimate material, as is the exhibition we are dedicating to him. Up until the opening on September 22, many days will be spent building, painting, felting, typesetting, printing, writing, cutting, hanging and pouring. For the celebratory opening, we have invited as our special guest, a robot who will greet the public.

REEM and REEM C at a Meet-and-Greet © PAL Robotics, Barcelona

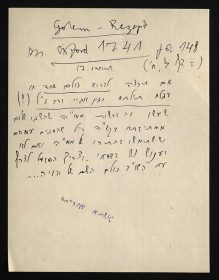

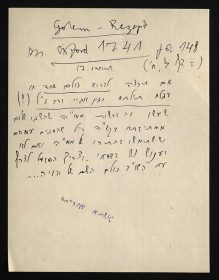

© Scholem Archives, The Jewish National and University Library, Jerusalem, Israel

But up until that moment, there is still a lot to be done. All of the objects and works of art have already arrived in Berlin. For example, the smallest item (14.5 x 11 cm), which is roughly the size of a post-it. On this piece of paper, Gershom Scholem (1897–1982), the scholar of Jewish mysticism, noted the beginning of the so-called “Golem Recipe,” which he had discovered in a medieval manuscript during his research at Oxford. → continue reading

A Conversation with Peter Weibel about whether Boris Lurie Should Be Seen as a Part of the Ultra-realist Neo-avant-garde, and Pornography as a Metaphor for Capitalist Society

Boris Lurie, “A Jew is dead,” 1964; Boris Lurie Art Foundation, New York, USA

Mirjam Bitter, blog editor: As part of the program accompanying our Boris Lurie retrospective, you’ll be giving a lecture at the Jewish Museum Berlin on 30 May 2016 on the subject of “The Holocaust and the Problem of Visual Representation,” (further details of which can be found in our events calendar). Is this tied up with the idea that the Holocaust is a major theme in Lurie’s work?

Peter Weibel

© ONUK

Peter Weibel: The Holocaust, along with war, Hiroshima, and Nagasaki were pivotal traumatic experiences for the post-Second World War neo-avant-garde. Take, for example, Yves Klein’s painting “Hiroshima” (1961) or Joseph Beuy’s environment “Show Your Wound” (1974–1975). Many artists responded to the inhumanity they had witnessed by calling into question humanity and indeed, civilization itself: Why, they asked, had literature, painting, music, and philosophy been unable to prevent this twentieth-century barbarism? → continue reading

A Guest Entry by Rudij Bergmann

Accompanying our current exhibition, “No Compromises! The Art of Boris Lurie,” Rudij Bergmann’s film about the artist will premiere on 21 March 2016 (additional information available on our event calendar). In this guest entry, the filmmaker tells us how this very personal documentary came about.

The artist’s longing for Europe was palpable from the moment I first saw him in the dim light of an apartment hallway on New York’s 66th Street. Stepping into his home studio, confronted by this breathtaking collage of memory, it was immediately clear to me that Boris Lurie hadn’t fully left the concentration camps he survived with his father – at least mentally.

It was October 1996. A film for the television magazine BERGMANNsART, which I’m for all intents and purposes responsible for, was the reason to rush to see Lurie in New York. (The film, in German and with age restriction, is available on YouTube.)

It was the beginning of a long friendship. → continue reading