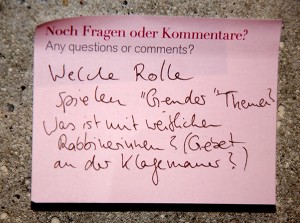

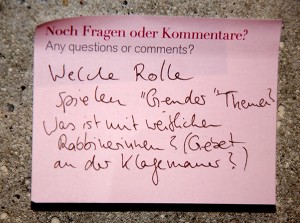

“What’s the story with women rabbis? (And prayer at the Western Wall?)”

The question of the month in the special exhibition “The Whole Truth”

© Jewish Museum Berlin, photo: Anina Falasca

Our special exhibition “The Whole Truth… everything you always wanted to know about Jews” is based on 30 questions posed to the Jewish Museum Berlin or its staff over the past few years. In the exhibition, visitors have their own opportunity to ask questions or to leave comments on post-it notes. We answer some of these questions here in our blog.

The question about the roles of men and women in Judaism is interesting because traditional notions about these roles have changed dramatically over the course of the last century. As in every religion, there are also many opinions about this issue among Jews. These correspond with the tendencies of orthodox, conservative, or liberal currents in Judaism, which – while they grapple with the same questions – come to quite different conclusions. → continue reading

or What We Can Learn from Loving Women

Not long ago, we happened upon the website of a group of three young Jewish women “who care about different aspects of Jewish and Israeli identity and culture and who want to experience a meaningful Jewish life in Berlin.” They call themselves Hamakom (Hebrew: ‘the place’) and support, among others, more frequent encounters between Israelis and Jewish Germans. The group’s first event is a Tikkun lel Shavuot on the topic of “Women & Love,” the title clearly stating the theme of the evening. The event follows the tradition of studying and discussing specific Biblical texts and their interpretations on the night before Shavuot. This choice of topic reveals the meaning the holiday has in the discursive process of self-reflection.

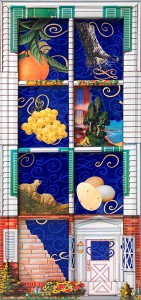

Jakob Steinhardt, Illustration to the Book of Ruth, 1955-1959, woodcut

© Jewish Museum Berlin, donation of Josefa Bar-On Steinhardt, Nahariya, Israel

Shavuot begins this year on the eve of 14 May and ends two days later. It is a holiday of unusually multifaceted significance, and it is rediscovered and redefined by every generation anew. Originally, the holiday celebrated the beginning of the harvest season, which included a pilgrimage to the Jerusalem Temple. Pilgrims brought their first fruit and two loaves of wheat-bread to the temple. In the Talmud, Shavuot is conceived of as the festival on which the population of Israel received the Torah. In preparation of this donation, the holiday is also described as an Atzeret, a joyous assembly, which involves a night of communal thinking and debating. Tikkun lel Shavuot, as this nightly symposium is called in Hebrew, means literally: ‘The betterment during the night of the Feast of Weeks.’ It was first mentioned in the kabbalistic Zohar-book and gained importance in the 16th century.

The Jewish understanding of collective studying and discussing differs from that of the Greeks; → continue reading

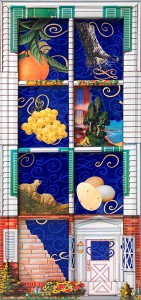

Seder Plate by Harriete Estel Berman, U.S.A., 2003 © photo: Jens Ziehe, Jewish Museum Berlin

Passover is not only a feast day evoking an historic event through a ritualized form of remembrance. It also appeals to reenact the exodus out of Egypt and envision divine mercy, freeing us from bondage and disenfranchisement. Like many Jewish holidays the original biblical Passover story has been and still is seen in relation to other historical events. The Egypt of the Exodus story turned into Ukraine and Belarus in the 17th century, when the Cossack chief Bogdan Chmielnicki allowed many hundreds of thousands of Jews to be murdered over the course of his struggle to liberate Poland. In the 20th century, Germany under the Nazi regime became the country to flee.

Through its culinarily-underscored recitation and discussion of the narrative, the seder provides a framework for each new re-interpretation. This appears primarily at the dinner: even while the symbolic dishes are determined by the Passover Haggadah, the other foods vary according to geography and the cultural conventions of the place where the celebration is taking place. There are especially numerous recipes for the “mortar,” the charoset, which resembles in color and texture the cementing agent used to build houses.

→ continue reading