An Interview with Alex Martinis Roe

Alex Martinis Roe, Encounters: Conversation in Practice, performance still, 2010.

Image courtesy of the artist.

To obtain a letter from a vending machine – even from an art vending machine – is rather unusual. In this interview, Australian artist Alex Martinis Roe explains what motivated her to create the artwork “A Letter to Deutsche Post.”

Christiane Bauer: Alex, you drafted a letter to Deutsche Post, asking the officers to reissue stamps depicting Rahel Varnhagen and Hannah Arendt. When our visitors purchase the letter, are they supposed to send it to Deutsche Post?

Alex Martinis Roe: I don’t expect visitors to send the letter to Deutsche Post, because I didn’t ask them to. They can do whatever they like with it. If they send it off, I’m happy. If they keep it, I’m also happy. (laughs) What I hope, is that they read the letter and become interested in the story.

Why did you choose to make a letter for the art vending machine? → continue reading

… the Auschwitz Trial Began 50 Years Ago Today

On 20 December 1963, Federal Germany’s largest and longest-lasting trial to date of crimes committed in National Socialist concentration and extermination camps opened in the council chamber of Frankfurt’s Römer, the city hall. On trial were twenty-two former staff members who had worked between 1941 and 1945 at the Auschwitz concentration camp. The highest-ranking defendant and last commandant of the camp, Richard Baer, had died just before the trial began. Many others did not face charges at all, not least because almost all crimes dating from the Nazi era were already time-barred—even homicide.

Hans Hofmeyer

© Schindler‐Foto‐Report

Since the Federal German legislature had not anchored the Allies’ postwar trials in Federal German law, trial proceedings in Frankfurt am Main—and likewise all subsequent trials of Nazi crimes—were based on the Penal Code of 1871. Consequently the only charges made were those of murder, and of aiding and abetting murder; and the court, under the guidance of the presiding judge Hans Hofmeyer, was accordingly obliged to find whether defendants had been personally involved in acts of murder, that is to say, had broken the law. → continue reading

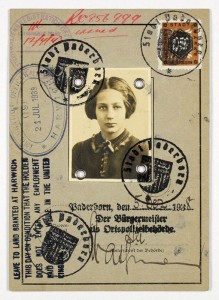

Beate Rose’s childhood passport

© Jewish Museum Berlin, donated by Beatrice Steinberg

75 years ago today, on 2 December 1938, the first of the Kindertransport rescue missions arrived in England. Beatrice Steinberg (née Beate Rose), a benefactor of the Jewish Museum Berlin, was among the last of the Jewish children to be saved in this way, by mass evacuation from Nazi-occupied territories. In her memoirs, which are held in our archives, she recalls her departure from Germany in the summer of 1939:

“My mother took me to the train, which turned out to be one of the last Kindertransporte to England […]. I was so excited that I rushed up the station steps without even saying goodbye to my mother. She called me back. We gave each other a hug and a kiss, then I boarded the train. I stood at the window and we waved goodbye. That was the last time I ever saw her.”

Beate Rose’s number tag from the “Kindertransport” rescue mission

© Jewish Museum Berlin, donated by Beatrice Steinberg

For Beatrice, only twelve years old at the time, the trip was an adventure; for her parents, the decision to let her go off alone, into the unknown, must have been made in great despair. The mass evacuation of children was launched three weeks after the November pogrom. Beate’s father was a prisoner in Buchenwald concentration camp at the time. Like hundreds of thousands of Jewish men and women, her parents hoped to leave Germany as soon as possible. But which country would open its borders to the mass of refugees? Visa restrictions and a bewildering amount of red tape made emigration a protracted and arduous undertaking. → continue reading