When German friends of mine choose to move from Darmstadt, in Hesse, into the surrounding countryside, I shake my head in disbelief. That an Israeli family would leave Tel Aviv not, as many Israelis do, to move to Berlin (see the German-language blog post offering ten tips for Israelis in Berlin), but rather to the tiny Hessian town of Niederbrechen, seems audacious, if not outright absurd. This scenario, however, is the starting point of Sarah Diehl’s debut novel Eskimo Limon 9. The novel depicts a “very particular kind of culture clash,” as the book’s flap announces.

Book cover

© Atrium publishers

Some of the characters are Israelis, and they have little interest in discussing Germany’s past or the history of European Jews.

“The only thing in the Jewish Museum that will remind me of home will probably be the metal detector you have to go through at the entrance.”

The novel’s Israeli father Chen wishes Germans “would associate us with Eskimo Limon instead of six million dead.” The title of the book refers to a film series of the same name, which aired in Germany in the 1980s as Eis am Stil (Popsicle), “one of the few Israeli pop culture phenomena […] familiar to German audiences.” Many assume that the series is Italian, which—as the author of the novel argues—shows how selective Germans’ perception of Israel can be, and how limited their idea of Jewishness often is.

Other characters are natives of Niederbrechen. → continue reading

Timber houses in the form of the Hebrew

letter Bet

© The Beit Project, photo: David Gauffin

Beit is the name of a European project thought up by David Stoleru, a Jewish architect from France. The name refers to the Hebrew word for house “Bajit” as well as to the letter “Bet” of the Hebrew alphabet. Stoleru has designed small timber houses that are somewhat reminiscent of the cozy beach basket chairs common on Germany’s Baltic coast. Seen from the side, they resemble the symbol ב for Bet, the first letter of the word beit. Several classes of eighth-graders set up such houses in the Heckmann Höfe in the Mitte district of Berlin, as a means to temporarily bring into the public sphere their nearby school, whose Hebrew name, Beit Sefer, literally means “House of the Book.” Here, for two days, they devoted themselves to the task of uncovering traces of the Jewish community in the local cultural and urban heritage.

It proved to be a strenuous two days’ work, during which the schoolchildren were almost constantly on the go and often had to push themselves to their limits. → continue reading

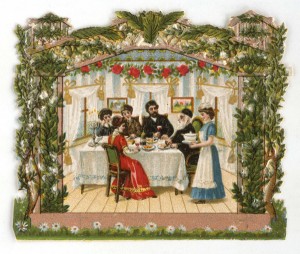

On 18 October, our next special exhibition “A Time for Everything: Rituals Against Forgetting” will open to the public. The exhibition met with great success at its previous venue in Munich. We therefore invited Bernhard Purin, director of the Jewish Museum Munich, to write a piece for our blog. He introduces us to an exhibit that is of relevance to this week’s holiday.

The Feast of Booths (“Sukkot” in Hebrew, from the word “sukkah,” meaning “tabernacle”) will be celebrated this year from 19–25 September. Along with Passover (Pesah) and Pentecost (Shavuot), it numbers among the three pilgrimage festivals, and commemorates the forty years Israelites spent wandering in the desert after the exodus from Egypt. The Third Book of Moses (23: 42–43) ordains:

“Ye shall dwell in booths seven days; all that are home-born in Israel shall dwell in booths; that your generations may know that I made the children of Israel to dwell in booths, when I brought them out of the land of Egypt: I am HaShem your G-d.”

Booths have been built ever since and their roofs covered with foliage, in keeping with this commandment. Rural Jews in Germany often erected such booths in the attic of their homes, and this tradition has been taken up at the Jewish Museum Franken in Fürth as well as at its Schwabach branch. Yet mobile booths which could be set up in the garden before the festival, then taken apart and packed away for the rest of the year, were also common. One booth of this kind survived in the village of Baisingen near Rottenburg am Neckar, where a large Jewish community once lived. → continue reading