An Appeal for Recognition and Dignity

“We used to throw stones at her – we thought she was a witch.” With these words, a former resident of Rishon LeZion ruefully told me of her childhood encounters with the sculptor and doll maker, Edith Samuel. Edith wore her long, dark, European skirts under the searing Middle Eastern sun and suffered from a physical deformity. The daughter of a liberal German rabbi, Edith and her sister Eva were both artists who left their home city of Essen in the 1930s and immigrated to Palestine.

The pottery wheel belonging to Paula Ahronson, Eva Samuel’s business partner, is preserved in private hands and untouched since her death in 1998

© Jewish Museum Berlin, photo: Michal Friedlander

The Samuel sisters worked long hours, struggled to earn a living and did not gain the recognition that they deserved, during their lifetimes. The exhibition “Tonalities” at the Jewish Museum Berlin aims to bring forgotten women artists back into the public arena. It presents Eva Samuel’s works and that of other women ceramicists who were forced to leave Germany after 1933.

My search for transplanted German, Jewish women in the applied arts began many years prior to my encounter with the Samuel sisters. It was Emmy Roth who first captured my attention. Born in 1885, Roth was an exceptionally talented and internationally successful silversmith, who worked in Berlin. She immigrated to Palestine and fell into obscurity, ultimately taking her own life in 1942. Her male refugee colleagues, Ludwig Wolpert and David Gumbel, were appointed to teach metalwork at the Jerusalem New Bezalel School of Art in the late 1930s. They are feted in Israel today, whereas Roth is still completely unknown there. → continue reading

Food for Thought from Our Recent Conference on “Migration and Integration Policy Today”

In the year 2000, the UN named 18 December International Migrants’ Day. Today, thirteen years later, Germany is well-established as a prime target country for migrants. Its population is plural, multi-religious, and multi-ethnic. Migration and integration therefore provide both politicians and academics considerable scope to tread new ground. But what state is migration and integration policy in today? And what role does academia play in shaping it? Which concepts have become obsolete, and which new perspectives are opening?

Panel discussion at the Academy of the Jewish Museum Berlin

© Jewish Museum Berlin, photo: Ernst Fesseler

On 22 November 2013, experts in migration research engaged in intensive and controversial debate of these questions at a conference jointly convened by the Jewish Museum Berlin, in the framework of its new “Migration and Diversity” program, and by the German “Rat für Migration,” a nationwide network of academics specialized in migration and integration issues. In the subsequent open forum with these invited guests, politics and science met head on: politicians and academics discussed, among others, migration policies proposed by Germany’s recently elected coalition government. → continue reading

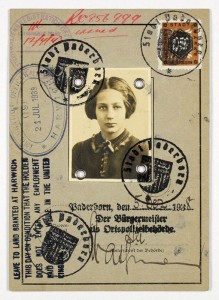

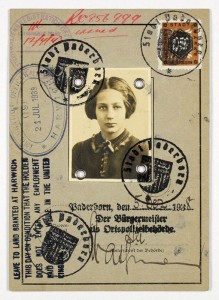

Beate Rose’s childhood passport

© Jewish Museum Berlin, donated by Beatrice Steinberg

75 years ago today, on 2 December 1938, the first of the Kindertransport rescue missions arrived in England. Beatrice Steinberg (née Beate Rose), a benefactor of the Jewish Museum Berlin, was among the last of the Jewish children to be saved in this way, by mass evacuation from Nazi-occupied territories. In her memoirs, which are held in our archives, she recalls her departure from Germany in the summer of 1939:

“My mother took me to the train, which turned out to be one of the last Kindertransporte to England […]. I was so excited that I rushed up the station steps without even saying goodbye to my mother. She called me back. We gave each other a hug and a kiss, then I boarded the train. I stood at the window and we waved goodbye. That was the last time I ever saw her.”

Beate Rose’s number tag from the “Kindertransport” rescue mission

© Jewish Museum Berlin, donated by Beatrice Steinberg

For Beatrice, only twelve years old at the time, the trip was an adventure; for her parents, the decision to let her go off alone, into the unknown, must have been made in great despair. The mass evacuation of children was launched three weeks after the November pogrom. Beate’s father was a prisoner in Buchenwald concentration camp at the time. Like hundreds of thousands of Jewish men and women, her parents hoped to leave Germany as soon as possible. But which country would open its borders to the mass of refugees? Visa restrictions and a bewildering amount of red tape made emigration a protracted and arduous undertaking. → continue reading