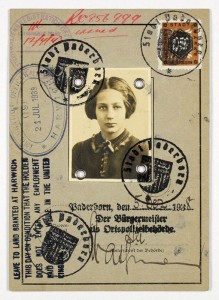

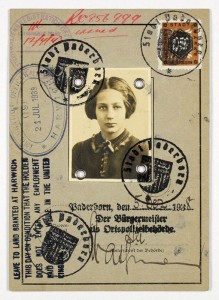

Beate Rose’s childhood passport

© Jewish Museum Berlin, donated by Beatrice Steinberg

75 years ago today, on 2 December 1938, the first of the Kindertransport rescue missions arrived in England. Beatrice Steinberg (née Beate Rose), a benefactor of the Jewish Museum Berlin, was among the last of the Jewish children to be saved in this way, by mass evacuation from Nazi-occupied territories. In her memoirs, which are held in our archives, she recalls her departure from Germany in the summer of 1939:

“My mother took me to the train, which turned out to be one of the last Kindertransporte to England […]. I was so excited that I rushed up the station steps without even saying goodbye to my mother. She called me back. We gave each other a hug and a kiss, then I boarded the train. I stood at the window and we waved goodbye. That was the last time I ever saw her.”

Beate Rose’s number tag from the “Kindertransport” rescue mission

© Jewish Museum Berlin, donated by Beatrice Steinberg

For Beatrice, only twelve years old at the time, the trip was an adventure; for her parents, the decision to let her go off alone, into the unknown, must have been made in great despair. The mass evacuation of children was launched three weeks after the November pogrom. Beate’s father was a prisoner in Buchenwald concentration camp at the time. Like hundreds of thousands of Jewish men and women, her parents hoped to leave Germany as soon as possible. But which country would open its borders to the mass of refugees? Visa restrictions and a bewildering amount of red tape made emigration a protracted and arduous undertaking. → continue reading

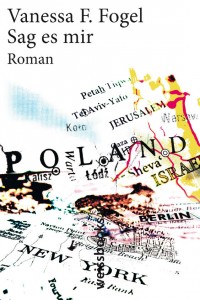

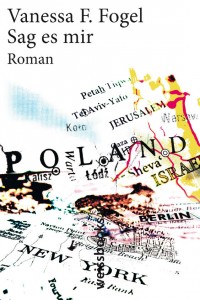

or “Being who I am”

“The night before I fly to Germany to see my grandfather Mosha, I meet someone, take him home with me, and for the first time in my life, I sleep with a man.”

© weissbooks.w

Frankfurt am Main

This sentence begins the first chapter of the 2010 novel Sag es mir (Tell it to me) by Vanessa F. Fogel. The author was born in 1981 in Frankfurt and grew up in Israel. She introduces the first-person narrator of this autobiographical novel both as a granddaughter and as a confident young woman right from the start. And despite her imminent trip to the sites of extermination – she meets her grandfather in Berlin and they travel together to Poland – her emphasis is on vitality and the joys of living.

The Frankfurt publishing house weissbooks has now taken on another Jewish writer of “the third generation.” Channah Trzebiner is a lawyer, also born in 1981 in Frankfurt, where, unlike Fogel, she still lives. She has written Die Enkelin (The Granddaughter), which is more of “a kind of inner monologue” than a novel. This book also begins confidently: “I accept the woman that I am.” At once, however, the author alerts her reader to the difficult process underlying this claim:

“For years I cut off my connection to the innermost ‘I’ […], so that I could be the substitute for a life ended by murder. How I could have done otherwise? I’m called Channah after my grandmother’s youngest sister […].”

→ continue reading

Area on the Majdanek Trial in the permanent exhibition

© Jewish Museum Berlin, photo: Alexander Zuckrow

Forty-four portraits have been mounted in the permanent exhibition over the last few weeks. They are a series of paintings by Minka Hauschild, called “Majdanek Trial Portraits,” and they show the participants of the Majdanek Trial, that took place at the regional court in Dusseldorf from 26 November 1975 until 30 June 1981. Standing in front of the wall of portraits, viewers are left to wonder: “Who is who, here?” The paintings themselves don’t reveal whether the subject was a former prisoner or an SS officer. Some portraits are realistic, but others seem distorted or blurred to the point of being unrecognizable. All of the people portrayed appear to have been damaged in some way. The portraits are deeply disturbing.

Our visitors can find out on iPads lying on the benches nearby whether a given painting depicts a judge, a lawyer for the defense, a witness, or a defendant. Each individual’s role in the Majdanek trial is described here and insight is provided into their biography as well as – where the sources permit – their own perception of the proceedings. → continue reading