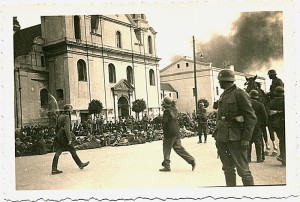

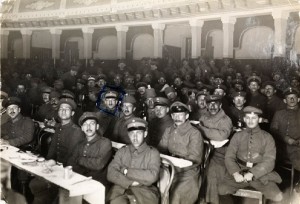

Photograph from World War II. The sellers priced it at 3000 euros.

The financial crisis of 2007 had an impact both on the countries of Western and Eastern Europe. The złoty may still glitter but it has long since ceased to be the “golden coin” Polish currency was originally named for. Unemployment and stagnant economic growth, rising real estate prices and declining purchasing power have put the brake on Poland’s economic recovery. The Netherlands has likewise been in recession for years. Declining competitiveness, private debts, state-subsidized home ownership, the low retirement age and the expensive health care system have fed uncertainty and repeatedly paved the path to success for the Freedom Party of the populist xenophobe Geert Wilders.

The Polish letter of offer as we received it.

This downward spiral in state treasury and personal funds led a couple of Polish resp. Dutch wheeler-dealers to scrape the barrel for a bilateral business model. Crafty Dariusz Woźniok and his fly-by-night Dutch client somehow managed to get their hands on infantrymen’s photos from the Second World War—whether as thieves or buyers it is impossible to say. Maybe they were embittered by the fact that no share in the tidy profits made from material goods ever came their way, from the export of Polish geese, strawberries, potatoes and beetroot, for example, or of Dutch cheese and tulips. Maybe they hatched their business plan in an Amsterdam coffee shop and had simply smoked one hash pipe too many. Whatever the case, they figured: “It was a sure bet that snapshots of ghettos and so-called ‘Jewish actions’ in early 1940s Poland could be sold off as ‘Holocaust-ware’ to Jewish Museums—so why not make the most of an historic windfall?” → continue reading

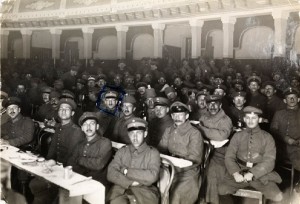

The Festival of Liberation at the Front

Yesterday evening, Monday, 14 April 2014, was the start of the eight-day Passover festivities. These kick off each year with the first Seder, the name of which derives from the Hebrew word seder, meaning order, because a particular ritual sequence is observed the entire evening.

The ritual Seder program is laid down in the Haggadah, an often beautifully illustrated book. (Incidentally, some especially precious Haggadot are currently on display in our special exhibition “The Creation of the World” and our director of archives recently described in his blog why even a nondescript Haggadah might be of great value to a museum.) Traditional texts and songs are recited from the Haggadah. Symbolic dishes and drinks deck the tables, ready to be consumed at specific moments during the evening.

German soldiers celebrate Passover in the occupied town of Jelgava (near Riga). © Jewish Museum Berlin, photo: anonymous. Donated by Lore Emanuel

But why is this night different from all other nights? This is a question that Jews all over the world ask themselves year after year at the Seder dinner. The answer is: it is the festival of liberation, for it commemorates the Israelites’ exodus from slavery in ancient Egypt. Everyone is supposed to feel, each year, as if she or he personally is about to leave Egypt. As a token of tribute to this new-won freedom, people comfortably recline while eating and drinking—for to take this position was the prerogative solely of free individuals in antiquity, not of slaves. → continue reading

An Interview with Cilly Kugelmann about the Exhibition “The Creation of the World: Illustrated Manuscripts from the Braginsky Collection”

Mirjam Wenzel: At the forthcoming exhibition, the Jewish Museum Berlin will present its first ever show of outstanding examples of the centuries-old Jewish scriptural tradition. What significance does scripture—the written word—have in the Jewish tradition?

Cilly Kugelmann and Mirjam Wenzel

© Jewish Museum Berlin, photo: Katrin Möller

Cilly Kugelmann: In early collections of rabbinic interpretations of biblical texts—the so-called midrashim—it is written that the Torah existed before the world was created. Some rabbis see the Torah quasi as a manual of creation that God drew on during his seven-day feat. Such interpretations demonstrate the extraordinary significance attributed to scripture in Judaism.

Following the loss of the geographic homeland Israel, sacrifices and pilgrimages to specific temples were abandoned in favor of prayer services that could take place anywhere—and the traditional texts themselves consequently became the most important, pivotal moment of the rite. To this day, the study and interpretation of biblical writings is the primary focus of Jewish intellectual life.

Why is René Braginsky’s Collection of illuminated manuscripts being presented under the title “The Creation of the World?” → continue reading