A Guest Entry by Rudij Bergmann

Accompanying our current exhibition, “No Compromises! The Art of Boris Lurie,” Rudij Bergmann’s film about the artist will premiere on 21 March 2016 (additional information available on our event calendar). In this guest entry, the filmmaker tells us how this very personal documentary came about.

The artist’s longing for Europe was palpable from the moment I first saw him in the dim light of an apartment hallway on New York’s 66th Street. Stepping into his home studio, confronted by this breathtaking collage of memory, it was immediately clear to me that Boris Lurie hadn’t fully left the concentration camps he survived with his father – at least mentally.

It was October 1996. A film for the television magazine BERGMANNsART, which I’m for all intents and purposes responsible for, was the reason to rush to see Lurie in New York. (The film, in German and with age restriction, is available on YouTube.)

It was the beginning of a long friendship. → continue reading

Program Director Cilly Kugelmann on the Exhibition “NO COMPROMISES! The Art of Boris Lurie”

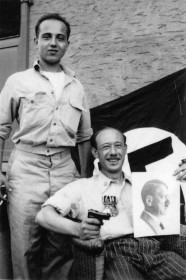

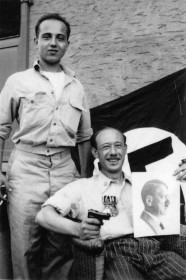

“As this image of Lurie with his brother-in-law Dino Russi from 1946 shows, the NO!art artists, in reclaiming the swastika symbol, robbed it of its symbolic value.” (Cilly Kugelmann)

Boris Lurie Art Foundation, New York

Our major retrospective dedicated to Boris Lurie opens 26 February 2016 (for more information see www.jmberlin.de/lurie/en). Blog editor Mirjam Bitter spoke with Cilly Kugelmann about the artist, his provocative work, and the possible impact today of the taboos that he broke throughout his career.

Mirjam Bitter: What is your view of Boris Lurie? What sort of a guy was he? What distinguished him as an artist?

Cilly Kugelmann: The man and the artist Boris Lurie was shaped by his experience of persecution and concentration camps under the Nazi regime. And yet, unlike other artists who faced similar experiences, I feel he cannot be described as a “Holocaust artist.” With the exception of some early drawings from 1946 and a few paintings from the late 1940s, he neither chronicled these events nor sought to interpret the Holocaust artistically in his work.

Then what role did the Holocaust play in Lurie’s work? → continue reading

View of the cabinet exhibition “In a foreign country. Publications from the Displaced Persons Camps” in the basement of the Libeskind Building.

© Jewish Museum Berlin, photo: Jens Ziehe

In our cabinet exhibition “In a foreign country” we explore the publishing operations of survivors and refugees, the so-called displaced persons (DPs) who were stranded in occupied Germany after 1945. For this show we selected the widest variety of genres: schoolbooks, Judaica, volumes of poetry and prose, historical documentation, and Zionist pamphlets.

They all have two things in common: first, the quality of the paper these post-war printers used was extremely bad. Second, they all come from the Berlin State Library, whom we’re hosting for this exhibition due to its historically valuable collection of DP literature.

With one little exception. → continue reading