The preparations for the exhibition R.B. Kitaj (1932–2007) Obsessions at the Jewish Museum Berlin have brought me back to Philip Roth. I try to re-read him about every ten years.

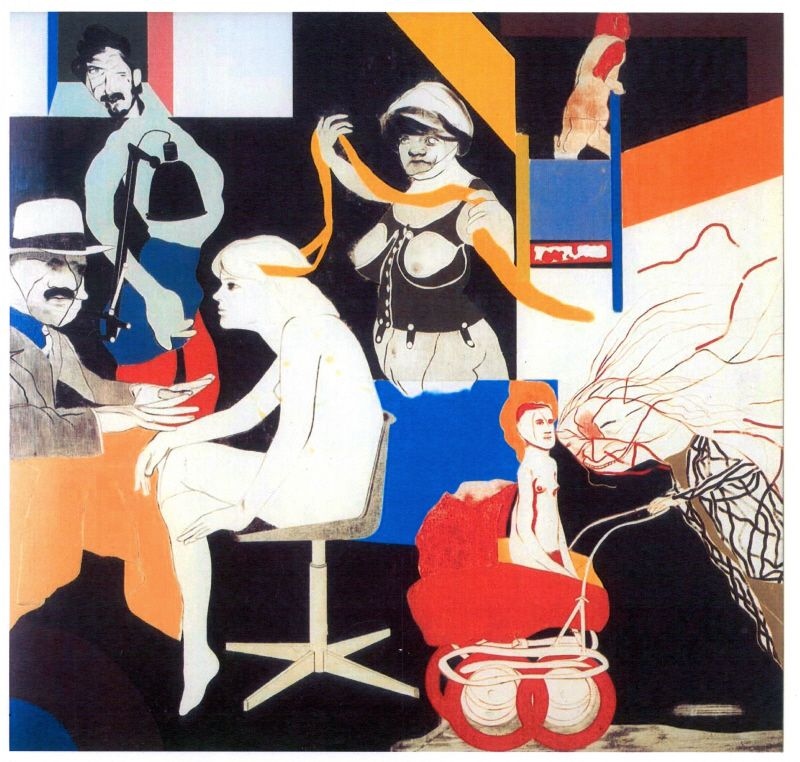

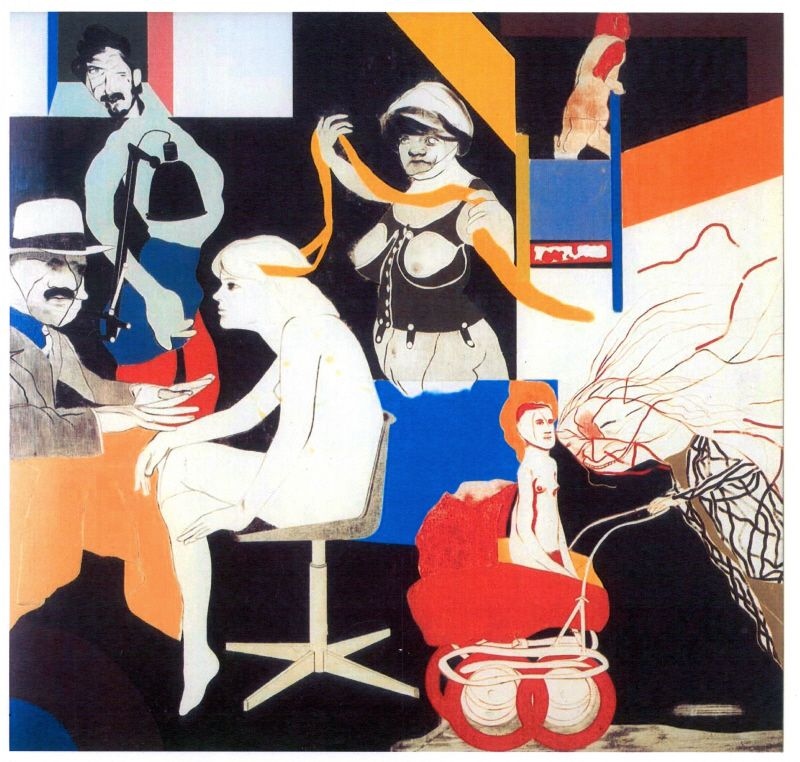

R. B. Kitaj, The Ohio Gang, 1964 © R.B. Kitaj Estate 2012. Digital image, The Museum of Modern Art, New York/Scala, Florence

Why? Out of curiosity; to test my feminist – or better and more simply, my feminine – distaste for Roth; to see if my increasing maturity has stimulated some new cognitive process that allows me to encounter the aging, sex-obsessed, white, male ego of the Roth hero with more empathy; or at last to discover exactly why Roth is a reigning great of American literature, which he undisputedly is. It is said that the lecherous puppeteer Mickey Sabbath of “Sabbath’s Theater” is modeled on the author’s neighbor and friend, R.B. Kitaj, but others of Roth’s characters bear traits or biographical details in common with the artist. To sum up, I can’t yet confess that Philip Roth’s characters appeal to me, but I do notice that they have become in a way “historical,” a portrayal of their time. It isn’t dissimilar to the way one enjoys the groping chauvinists of Mad Men, without necessarily wishing to return to the age of oversexed secretaries and mousy housewives. In any case, the projected figure of the artist R.B. Kitaj has grown more vivid, more three-dimensional in my imagination – and I’m all the more excited to get acquainted with the “real” Kitaj beginning in September through the paintings at the Jewish Museum.

For more on R.B. Kitaj, see: www.jmberlin.de/kitaj/en

Signe Rossbach, Events curator

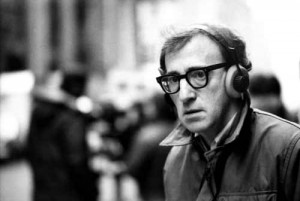

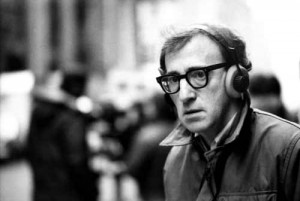

Woody Allen: A Documentary presents the life and work of one of the most influential Jewish filmmakers of the past half-century. In a series of interviews, colleagues and peers tell anecdotes and bestow panegyrics on Allen, among them Martin Scorsese, Diane Keaton, Scarlett Johansson, Naomi Watts, and Stephen Tenenbaum.

Woody Allen, © MCM, Foto: Brian Hamill

Unfortunately, few say more than what a “great guy” Allen is and how fantastic it is to work with him. The movie hints at, but misses every opportunity to ask more pertinent questions: How does Allen understand his Jewish background as a source and subject of his humour? Growing up in New York of the 1940s, how did National Socialism shape the neurotic Jewish characters he embodies in his films? What “in the early 1940s” turned him, a happy toddler, into a grumpy child? And why does he type his screenplays on an antiquated German typewriter he compares to a tank, which he believes will outlive him? A cinematographic equivalent of yellow press reporting, the film doesn’t do justice to one of the more subtle and intellectual figures in popular culture. (Woody Allen: A Documentary, directed by Robert B. Weide)

Naomi Lubrich, Media

One task that all of us working at the Jewish Museum share, one that is unwritten, undocumented, and often even unnoticed, is tracking and evaluating Jewish-related discussions and trends. Who is surprised by the Cologne verdict on circumcision? Who is still optimistic about the Arab Spring? Who is tired of all-white “apple design” for everything related to culture, even Jewish culture? Between doorways, at the photocopy machine, at the canteen, these comments unconsciously shape our work, influence our choice of topics and define the museum’s mission. We thought it might be worthwhile to voice some of our opinions and chose a budding literary genre: part lunch conversation, part feuilleton, part diary, part text message. Welcome to the blog of the Jewish Museum Berlin.