They betray the hopes, dreams, and projections of fathers and mothers,they follow trends, and foretell the future of their bearers.

For Jews many decisions are connected to the naming of a child: should the name underscore his religious affiliation, only be recognizable to other Jews, or neither? Will it be a name native to the family’s country of origin or to the child’s country of birth? Has the name been translated? Does it memorialize someone? Colleagues and friends of the Jewish Museum Berlin share their thoughts with this blog, on this and other questions.

Miriam dancing © Miriam Lubrich

Miriam / Mirjam

Soon there will be four women working along the hallway that my office is on, who all have the same first name that I have: Mirjam or, in some cases, Miriam. Even while the etymology is not completely unambiguous, the triumphant prophetess with the timbrel is namesake to each of us – that Miriam who roused the women to dance a dance of joy after the Israelites had fled from Egypt and divided the Red Sea (2. Moses 14, 20). With that, the sister of Moses and Aron took her rightful place among scripture’s female figures – women like both of the wives of the first man Adam, Lillith and Eve – who showed their rebellious traits: Miriam asserted the claim that God also spoke through her. She was consequently struck with a skin rash and had to wait for seven days outside of the encampment before she was allowed to live among the congregation of her desert-crossing brethren (4. Moses 12, 1-16).

Is it an accident that this combative woman lent her name to so many employees of the Jewish Museum Berlin? → continue reading

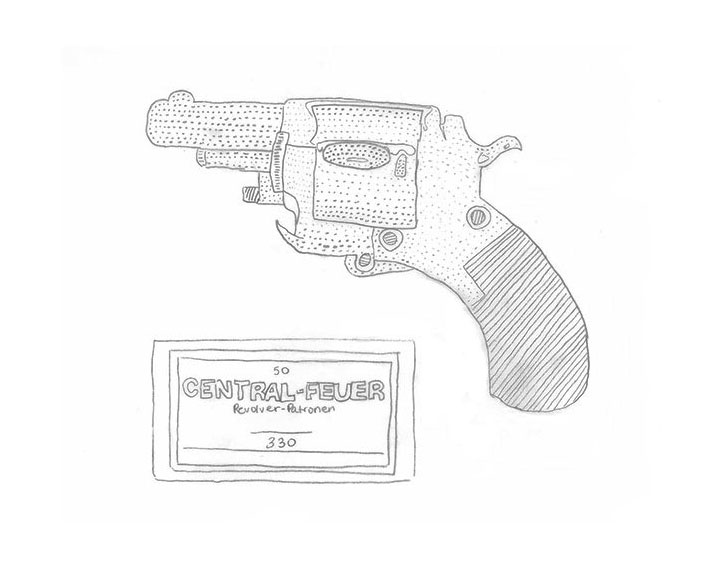

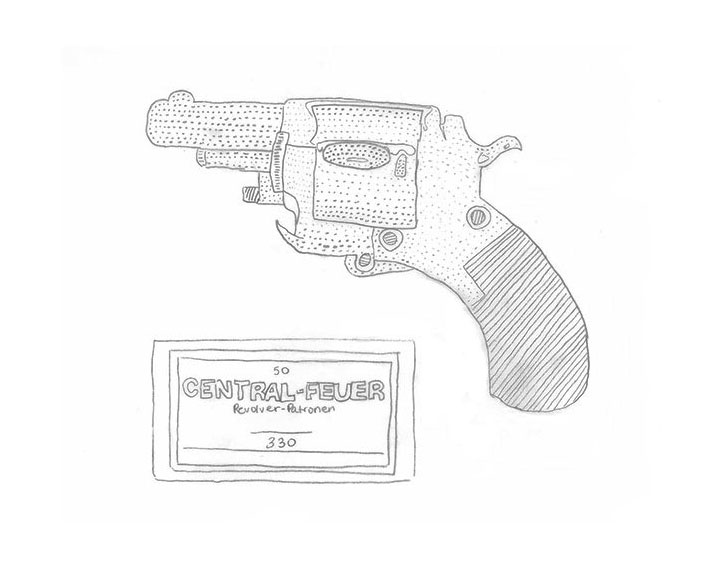

“Weapons and Dignity” is the title of the chronicle of an object in the recently published 25th anniversary brochure of the German Historical Museum. It is about a revolver that was offered as a donation to the Jewish Museum, met with great interest there, but finally found its way into the collection of the German Historical Museum. Why?

“Weapons and Dignity” is the title of the chronicle of an object in the recently published 25th anniversary brochure of the German Historical Museum. It is about a revolver that was offered as a donation to the Jewish Museum, met with great interest there, but finally found its way into the collection of the German Historical Museum. Why?

The story: a woman in Berlin during the National Socialist era, fearing for her life because she was ‘half-Jewish,’ obtained a revolver so that, should she be threatened with deportation, she could end her life instead. She survived the era of persecution and kept the revolver as a souvenir, eventually giving it to a neighbor. He in turn made contact with the Museum when he was to be required by changes in the law regulating weapons possession to register the weapon or surrender it to authorities. For an institution like the Jewish Museum Berlin, where biographical narratives play an important role in the collections and in the permanent exhibition, this revolver would have been a very welcome ‘strong’ object, given the immediacy of its provenance. → continue reading

“It didn’t begin until 1935, when I was sitting over a newspaper in a Vienna coffeehouse and was studying the Nuremberg Laws, which had just been enacted across the border in Germany. I needed only to skim them and already I could perceive that they applied to me. Society, concretized in the National Socialist German state, which the world recognized absolutely as the legitimate representative of the German people, had just made me formally and beyond any question a Jew, or rather it had given a new dimension to what I had already known earlier, but which at the time was of no great consequence to me, namely, that I was a Jew. → continue reading